It’s on Ed’s

blog Les Cahiers-Positifs that I

discovered Godard also reviewed Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). I thought he only reviewed Strangers on a Train and The Wrong Man by Hitch. I guess, I was

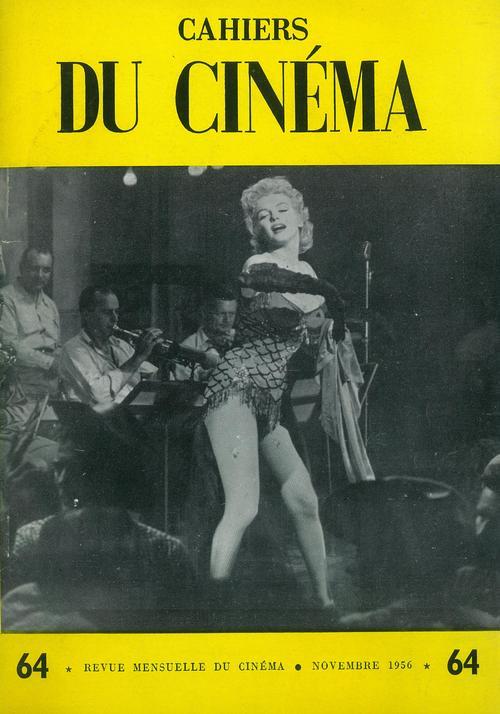

wrong. It happens. Anyways, on the cover of the November 1956 issue of Cahiers (N.64) there is a still of

Joshua Logan’s Bus Stop with Marilyn

Monroe, which is reviewed by Jacques Doniol-Valcroze (a critic whose output

deserves more attention). The early defining features of Cahiers are: André Bazin’s friendship with François Truffaut, the

young critics fight to take over the magazine, and Hitchcock as a defining

figure for the group. The Critiques were, and are, the most important section

at Cahiers – their chronicle of the

films, and the times – and these early Hitchcock reviews are the seeds that the

magazine would grow out of. (More so than those on Nick Ray, whose affinity never really left the magazine). Even Truffaut and Godard, whose friendship broke in

the post-’68 years (c.f. their last correspondence), would remain loyal to

Hitchcock throughout their whole careers: the Hitchcock interview book for Truffaut and Godard, who would return

more to narrative filmmaking after Truffaut’s death (a reconciliation?), in his

Histoire(s) describes Hitchcock as

the “greatest creator of form in the 20th century.” Hitchcock would also play a

significant role when the magazine renewed itself in the Eighties through their critical appreciation of Brian dePalma and how his films interrogate Hitchcock’s impulses and artistry. And Hitchcock is also at the root of their current appreciation of Steven Spielberg and

how he is able to mediate between personal projects within an industrial studio

system. – D.D.

***

The Student’s Path

One market

day an Allied secret agent, disguised, of course, as an Arab, is killed right

in the middle of the crowd in Marrakech. An important diplomat is shortly to be

assassinated. Before he dies, the spy manages to whisper his secret to an

innocent witness to the crime, an American tourist who is then uncertain

whether or not to pass it on in his turn to the (ex) French police in Morocco.

A telephone call helps him make up his mind to say nothing. His little boy has

been kidnapped, says a voice at the other end of the wire, and if he talks, he

and his wife will never see their child again. An incredible but very real

threat, which instantly fills our two Babbitts – James Stewert as a doctor from

Indianapolis and Doris Day as a once-celebrated singer – with alarm. Neverless,

like a modern Robinson family, they launch out into the unknown, following

their adventure without losing heart. Where to? To London. They have reason to

believe that the plot will unravel there. Zig and Puce on Dolly’s trail could

not show more heroism or more commend sense. Chance it and trust to God. Que sera, sera. This is also the opinion

of Scotland Yard, who are waiting as they leave the plane. An important

official wants to take the affair in hand. He fears complications of the kind of

French Cabinet calls ‘cosmic’. Is it worth the risk of aggravating an already

tense international situation for a little boy? James Stewart and Doris Day say

yes. Who can blame them? We, too, have little boys, or maybe little girls. But

no matter – they must act. And, in fact, with a little luck – but they earn it

– our amateur Perry Masons soon pick up the kidnappers’ trail, meanwhile

unwittingly foiling the plot of a foreign Power which has once again tried to

undermine the prestige of old England.

It

is easy to see what is likely to shock the susceptible in this story: the touch

of extravagance and, what obviously attracted Hitchcock, the introduction of

this extravagance in lives as ordinary as yours and mine. This is perhaps the

most improbable of Hitchcock’s films, but also the most realistic. What is

‘suspense’? Waiting, and therefore a void to be filled; and more and more

Hitchcock loves to fill it with asides which have little bearing on the event.

When

he leaves the studio to shoot on location, the director of To Catch a Thief allows his actors more freedom, lets his camera

linger on a landscape, seizes neatly and firmly on every droll character or

bizarre object to come his way. The scenes in the bedroom, the Arab café, the

two police offices (French and English), the taxidermist’s shop, the

Presbyterian chapel, the concert or the embassy ought, if they are logical, to

make all the Buñuels and Zavattinis of this world pale with envy. Today Alfred

Hitchcock looks all round his characters, just as he forces them to look round.

Not that he ever loses interest without tenderness, he had never before

stressed with such fierce irony the ridiculousness of the most natural.

Everyday gestures. The characters in The

Man Who Knew Too Much are not exactly puppets, they are at once more and

less than the marionette described by Valéry.

All

right, you will say, but what about the suspense? A booby-trap? I don’t think

so, here even less than in the other films. Firstly, because the extraordinary

serves as a foil for the ordinary, which, left to its own devices, would

engender nothing but dullness. Secondly, one must admit, because Hitchcock

believes in destiny. He believes with a smile on his lips, but it is the smile

which convinces me. If the story were simply frightening, perhaps we would not

be naïve enough to play along. Hitchcock cunningly presents us with a well-bred

destiny, speaking the language of the drawing-room rather than of German

philosophy. The clash of cymbals has the affection disguise itself, to sneak by

without drawing attention to itself. People say Hitchcock lets the wires show

too often. But because he shows them, they are no longer wires. They are the

pillars of a marvelous architectural design made to without our scrutiny.

Que sera, sera: this time, whether you like it or not, it is

explicit in the text. I know Hitchcock doesn’t believe it entirely, for the

moral of the film is also ‘God helps those who help themselves.’ ‘When

Stavrogin believes,’ wrote Dostoyevsky, ‘he does not believe that he believes,

but when he does not believe, he still does not believe that he believes.’

But we can believe in Doris Day’s tears, and no

other Hitchcock heroine’s tears seem so unlike face-pulling. We who know all,

and know that her alarm is needless, perhaps we sympathize even more readily.

Why does she weep? Why does she wail? What has she to do with this foreign

diplomat? Is she so crazy, so imprudent? She is a woman, or rather she is like

us all. We believe in suspense. We believe in destiny. Our anguish is increased

by what we know, hers by what she does not know. We watch her with a touch of

cruelty, a half-feigned terror, and a pity of which we did not know ourselves

capable.

This film by a

supposedly misogynous director has as its sole mainspring = assuming one

resolutely rejects metaphysics – feminine intuition. It is, like assuming one

resolutely rejects metaphysics – feminie intuition. It is, like his preceding

films, without self-indulgence, but the better displays its moments of grace

and liberty. Sometimes, like the little boy held prisoner in the embassy who

hears his mother’s voice as she sings in the salon, we are touched in

the work of his caustic and brilliant man by a grace which may only come to us

in snatches from afar, but which minds more immediately lyrical are incapable

of dispensing with such delicacy.

Let us love Hitchcock

when, weary of passing simply for a master of taut style, he takes us the

longest way round.

Jean-Luc

Godard