The idea behind the “Toronto on Film!” series is to share important and undervalued films that have been made in this country. It’s meant to be a cinémathèque for older films that aren’t necessarily recognized as classics but that are important historically, aesthetically and socially as a way to explore the richness and diversity of Canadian cinema and more specifically Toronto films. Instead of attempting any form of totalizing gesture to explain what Canadian cinema is (as per the tradition in many ‘official’ world cinema anthologies), this series begins with the specific: not only is its goal to introduce, show and discuss a ‘Toronto film’ but its project is quasi-archeological as the films that will be emphasized will ideally be outside of the public-domain, forgotten about and unearthed from the archives. By being specific, through starting the conversation around particular films and their directors, the aim of this series is to go against preconceived notions of Canadian cinema and to show its heterogeneity. Canadian film scholarship should be more than just the re-writing of twice-told clichés but instead it should be about bringing something out of the past to illuminate the present. It should involve showing the work and sharing it with others. It has to mean something for more than just one person.

The cinémathèque quality of the “Toronto on Film!” series comes from how it will program older work. As interesting as some new short- and feature-length films can be, there is a sense, in Toronto specifically and I reckon nation-wide too, that knowledge of Canadian film history is lacking and, if you’ve even gotten around to take a Canadian film course, too predicated on certain ‘mainstream’ titles. The idea that Canadian film history should be restricted to feature-length narrative films is also limiting. So instead “Toronto on Film!” will open itself towards alternative media objects: the short film, NFB documentaries and television.

This is in response to a general apathy I see towards the topic of Canadian film history. It’s always sad to hear that folks don’t watch any Canadian films. It’s always sad to hear emerging Canadian filmmakers looking up to someone like Denis Villeneuve for inspiration or looking up to Netflix as a place for where they can make ‘universal’ content. This is how regional specificity gets loss and it erases such a rich and exciting film history to draw inspiration from.

For example, last season we showed Glenn Gould’s Toronto (1979) with its filmmaker John McGreevy in attendance. In his best-known City Series, he would get famous guides to provide tours of the world’s urban metropolises: Elie Wiesel in Jerusalem, John Huston in Dublin and, in the work that we showed, Glenn Gould in Toronto. What makes the later so special is that Gould, who is known for his genius piano skills and reclusive temperament, opens himself up, with the help of McGreevy, to the simple pleasures and quotidian life of the city that he has always called home, while also expressing doubt and reticence towards its urban expansion. More people should be discussing McGreevy. His extensive filmography is well worth taking the time to explore. The archive for McGreevy Productions is available at Media Commons at the Robarts Library on the University of Toronto campus.

The 2019 Winter Season of “Toronto on Film!” should be equally exciting as we’ll be focusing on the pioneering filmmakers Martin Defalco, Jennifer Hodge de Silva and Peter Lynch.

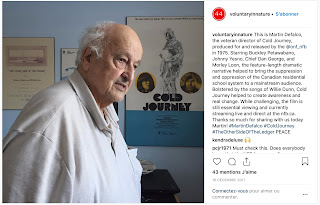

Indigenous filmmaking in Canada is now more important and vital than ever. So I want to look back at one of the ground-breaking indigenous feature-length films: Martin Defalco’s 1975 NFB-produced narrative film, Cold Journey. It’s a film about the negative effects of colonialism and the violence of cultural erasure that took place through the federal residential school initiatives, which forced the separation of indigenous children from their parents and then punished them for holding on to their values and not assimilating. Martin Defalco has a unique approach that is noteworthy: he casted non-professional indigenous actors in the lead roles and remained steadfast to the necessity of bleakness to end the story. These traits would be held against the film at its initial release, along with a lack of a theatrical infrastructure, that led to it not reaching an audience. That Cold Journey was made back when it did is incredible. Defalco needs to be recognized as one of the master indigenous filmmakers alongside Gil Cardinal, Alanis Obomsawin and Zacharias Kunuk; and Cold Journey needs to be recognized as one of the masterpieces of Canadian cinema up there with Nobody Waved Good-bye (1964), La vie heureuse de Léopold Z (1965), Crime Wave (1985) and Loyalties (1987).

Defalco’s work in general deserves a critical reappraisal for how it treated indigenous cultures and interests within the constraints of National Film Board projects. There are the more explicit works like The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson's Bay Company (1972) that was co-directed with Willie Dunn, which deals explicitly with how social welfare and trading shops exploited indigenous communities; and Trawler Fisherman (1966) about the negative effects of industry expansion in the Northern Saskatchewan countryside that spoiled the water with high mercury levels and prevented and reoriented traditional fishing lifestyles. Defalco’s work presents indigenous communities with a great deal of care and dignity along with a rage and resourcefulness in regard to their maltreatment. You can also see how this permeates through environmental themes that keep resurfacing in his other work like Northen Fisherman (1966) and Class Project: The Garbage Movie (1980).

The availability of these works on the NFB’s website is part of a larger project to promote indigenous cinema, which has only been growing in the last few years. They currently have five of Defalco’s films online, even though there is still a lot more of it to make public. I also want to highlight Donald Brittain’s Starblanket (1973), on the young indigenous chief Noel Starblanket, which is part of this larger project. Starblanket is particularly relevant in regard to the film Cold Journey as he was the one who suggested to Defalco to make the film and he would have a small role in it. Defalco’s work shows such a great respect for the documentary and its form while also having a faith in its advocacy potential to create real social change. For these reasons alone, it makes Defalco one of the best filmmakers to have worked at the NFB.

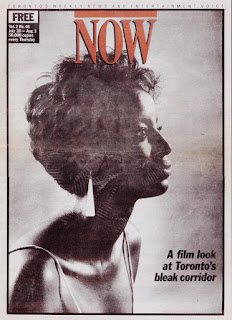

The “Toronto on Film!” screening at 2:30PM on Sunday, February 10th should not be missed. It will spotlight the pioneer African-Canadian filmmaker Jennifer Hodge de Silva. Her most famous work is Home Feeling: Struggle for a Community (1983) that was co-directed with Roger McTair, which looks at the Jane and Finch community in Northern Toronto by focusing on the folks, most notably its Caribbean population, that are effected by structural injustices and police discrimination. Go watch this on the NFB’s website right now if you haven’t seen it yet. Cameron Bailey, who wrote the definitive essay on her writes, “Whether or not future histories of black filmmaking in Canada begin with Jennifer Hodge de Silva, they will have to acknowledge her importance.” It’s an injustice that not more of Hodge de Silva’s work is available. Luckily I found two works related to her at the Ryerson University Library: Toronto's Ethnic Police Squad (1979) and a documentary about her Jennifer Hodge: The Pain and The Glory (1992) by Roger McTair and Claire Prieto (both of whom are impressive filmmakers and authors in their own right). I’ll do my best to try to get a speaker to come.

While for the March event we’ll look at two of Peter Lynch’s film: the Toronto-centric short-film Arrowhead (1994), which stars Don McKellar, and also his newest film, Birdland (2018). This screening is organized by fellow film studies graduate student Meghan McDonald. The director will there in attendance for this screening to give an introduction and participate in a post-screening discussion. It will be at 2:30PM on Sunday, March 3rd at the Theater in Media Commons at Robarts Library.

If you haven’t heard of or seen any of these titles I wholeheartedly recommend you check out at least one of the screenings. It’s what a Canadian open fault should look like.