One of the gems from 1982 at Cahiers du cinéma are its two Made In U.S.A.

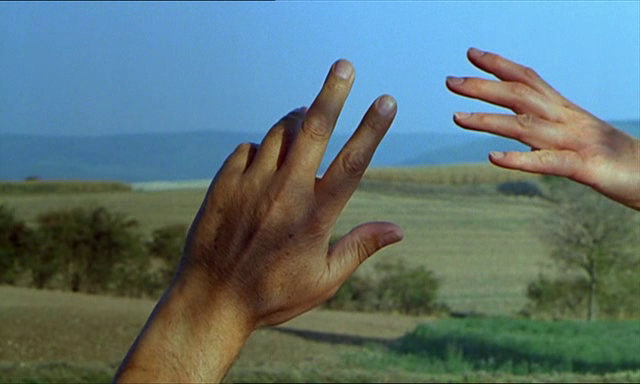

issues from April and June (N.334-35 & N.337). The former has a Manny Farber painting on its cover while the latter has a still from Wim Wender’s

Hammett.

One of the gems from 1982 at Cahiers du cinéma are its two Made In U.S.A.

issues from April and June (N.334-35 & N.337). The former has a Manny Farber painting on its cover while the latter has a still from Wim Wender’s

Hammett. These issues were a major initiative at Cahiers to return to writing more about a popular American cinema that was dropped for them in the Seventies where instead they were writing more political and theoretical texts. These issues are of great cinephilic interest not only for the information and perspective, but also as historical documents.

In the opening editorial, Vingt Ans après, Serge Toubiana writes, "With this Made in U.S.A. issue, Cahiers is returning to a tradition of special issues dedicated to American cinema that was inaugurated in 1954 (N.54), continuing in 1963 (N.150-51) and that has been subsequently dropped over the last 20 years." In the editorial Toubiana elaborates on the actualities of filmmaking in both France and in America, and what these possibilities mean for the future of cinema.

In the first issue there are features on prominent American auteurs. In this section there are interviews between Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader, Brian de Palma and Serge Daney with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Peter Bogdanovich and Olivier Assayas with Bill Krohn. There are also interviews with producers and technicians, guest contributions by Todd McCarthy and Lise Bloch-Morhange, an interview with Manny Farber, a visit to the Zoetrope Studies, a trip to Budd Boettichers, a text by Sam Fuller on White Dog, Cahiers Critiques on recent American films (e.g. Pennies from Heaven, They All Laughed), and an American-focused Le Journal section.

The Cahiers filmmaker that is

conspicuous by his absence, though he is frequently mentioned within the issues, is Steven

Spielberg. This omission might have

had more to do with the filmmaker's unwelcoming public relations than it did a lack of interest on Cahiers' part.

The following is the De Palma interview with Daney and Rosenbaum which I consider perhaps one of the best, and most important, interview with the filmmaker, since it would cement the importance of De Palma at Cahiers, which was initiated a few issues earlier with Douchet décortique De Palma (cf. my translation), and who is still being championed today.

The interview is from Cahiers du cinéma Presents: The Hollywood Interviews (Berg, 2006), while I translated its original introduction.

The following is the De Palma interview with Daney and Rosenbaum which I consider perhaps one of the best, and most important, interview with the filmmaker, since it would cement the importance of De Palma at Cahiers, which was initiated a few issues earlier with Douchet décortique De Palma (cf. my translation), and who is still being championed today.

***

New York. "Yes, what happened to you guys?" This is the first response that Brian de Palma gave us. How could, Cahiers du cinéma, miss my films for ten years? A serious questions. We are embarrassed. Of course, since Jean Douchet encouraged us to dissect De Palma (Journal des Cahiers, N.326) and since I attended a frantic projection of Blow Out, with Travolta in presence, I know that our injustice towards De Palma will be unmasked. It is a matter of months, weeks, and days. That's it.

I didn't really expect that in the current American film landscape - flabby and full of itself - a film by De Palma, even bloody, morbid and dirty, was - paradoxically - a breath of fresh air. What asphyxiates the young tycoons of the American cinema, is their love of an already finished cinema, of the finished product, for their hyper-culture.

What makes a film of De Palma breathe, is this pleasure to create, an inheritor of the mineur of yesteryear's American cinema. De Palma creates a film like Hitchcock, but between the two words it is "creates" that is the most important. And because it must be said De Palma is really different from Hitchcock, I think the opposite and would say that I find in him the qualities of the older Hitch, read the first Hitchcock, from the British period. There's even the same funny mixture of the cinematographic kitchen (an aspect "amateur filmmaker," tricks, formal structures, a taste for rhetoric, a positioning for the viewer - and therefore a morality) and of a sociological kitchen (trivial scandals, a direct naturalism, themes of urban life, and crimes that are always sexual).

It is the mixture of these two types of kitchens that make the films of De Palma, to use the qualitative sense, popular. He lives in the heart of the contradictions that made Hitchcock. His films please the large public and the cinephiles, displeases the establishment, and create a kind of cult. De Palma, of course, doesn't worry too much about this. He chases the major commercial success with the same obstination that he puts into not waiving his creative process.

It is the mixture of these two types of kitchens that make the films of De Palma, to use the qualitative sense, popular. He lives in the heart of the contradictions that made Hitchcock. His films please the large public and the cinephiles, displeases the establishment, and create a kind of cult. De Palma, of course, doesn't worry too much about this. He chases the major commercial success with the same obstination that he puts into not waiving his creative process.

His life has order, and his time is precious. On his desk, there is a gridded paper that is used as a calendar. On the wall nearby there is a neon sculpture that evokes Phantom of the Paradise. We feel that the filmmaker needs to capture all the energy of a true Babel or of a modern Babylon. New York, justly. - S.D.

Cahiers:

We’ve never interviewed you for the Cahiers

du cinéma. It’s time we made up for that.

Brian

De Palma: Yes. What were you up to?

Cahiers:

Let’s begin with a general question. It seems that a lot of the political and

social preoccupations that were in your first films have become less important

in your later ones. And yet you seem to be returning to them – in Blow Out, for example, and in your

project Act of Vengeance, based on

the murder of Joseph Yablonski, the reformist head of the United Mine warriors,

and his family in 1969.*

De

Palma: Yes, that’s true. A lot of the movies

I was making in the 1970s were fashioned, they had a kindof style. But now we

are in the 1980s, I’m forty years old and I’m trying to include certain

political features as I did at the end of the 1960s. But, because of economic

problems, it’s difficult to make political films in the States and to make them

pleasant, understandable or interesting.

C:

Was Greetings successful?

BDP:

Yes, but a lot of political films that were successful in

the 1960s would not be now. At the time the Revolution was all the rage and

everyone was more or less interested by everything that was against the

Establishment. But it was cheap to do and the American film industry had a huge

amount of money at its disposal. Small budget movies are rarely successful in

the States. Three years ago I made Home

Movies, which cost about $300,000. Ten years ago I would have needed

$25,000 to make a small budget moves. It’s a hundred times more now; I don’t

know whether it’s because of inflation or simply because the cost of films has

changed. To make a film and distribute it cheaply is more or less impossible.

C:

Do you think videocassettes will change that?

BDP:

Certainly. I hope very much so, because I can’t imagine what a young directors

can do now. It’s difficult to finance a film independently and almost

impossible to release it. Who are the young directors, ten or fifteen years

younger than us, who will go through a movie industry that doesn’t encourage

them to make experimental or revolutionary films or any other sort? In my

opinion the worst thing you can say about films nowadays is that they are

television films. What interest is there in releasing them through the cinema?

C:

Of your own films do you prefer the ones that were financially independent?

BDP:

When, like me, you have had a certain success in the film world, it doesn’t

really matter whether you are financed by the studios or not because there

aren’t the same sorts of control as when you are a young director. When you

have made a name these problems don’t exist.

C:

Had you reached that stage with Carrie?

BDP:

Sure. I’d already made Get to Know your

Rabbit for Warners, but I was young and I had nothing more to give.

C:

Last night I saw One

from the Heart [Francis Ford Coppola, 1982] and I had the impression that

even to tackle a small subject with a more or less non-existent story a lot of

money is necessary and that this money should be visible on the screen. And perhaps

that’s what the American cinema is suffering from today. It has to cost a lot

of money and sometimes that isn’t evident.

BDP:

When you speak of somebody like Francis Coppola that’s something quite

different. Can see what you mean. You’re talking about a kind of capitalist

snowball that grows and grows, but with Francis I think it’s different. I’m a

bit surprised and I talk with my friends about it all the time. Important

directors like Coppola, Bogdanovich or Friedkin, who were superstars at the

start of the 1960s, are now making films costing a lot of money that have been

commercial flops whatever their artistic merits. And yet they are so important

that it’s like “The Emperor’s New Clothes”: they hold court, they live in grand

houses always full of people; everything is filtered and watered down so that

they have no negative feedback: they are geniuses, billionaires…

C:

It’s like being in government.

BDP:

Precisely – to the extent that you are so well protected that you don’t have to

face up to what isn’t working in what you are doing. I think Francis’s problem

is that everything he makes somehow has to be a masterpiece. In One from the Heart there’s all this

technical rubbish. And Francis is a past master when it comes to manipulating

the press and the media and being seen everywhere. But I seriously think that

the American system destroys creative talent. It’s what has happened to these

filmmakers, it’s because they are so isolated that they have no way of knowing

where they are at. It’s interesting to note that the American film industry and

the importance of directors are often linked to the big studios. The director

is now God and the driving economic force, so there are no more limits, no more

barriers. And the result is excess – like those unbelievable castles of mad

emperors. It can happen to any one of us and it scares me because these people

have talent.

C:

And what have you done to avoid this danger?

BDP:

Various things have saved me. First of all I’ve never had a big success – all

my successes have been modest ones, and I’ve always had to fight for the films

I’ve wanted to make. That’s not to say that I wouldn’t have had those problems

if I’d had a major success. But personally I often see what’s not right. I

don’t look for shelter. I make myself watch those of my films that have not

worked to see what was wrong with them.

C:

Do you think film criticism is useful?

BDP:

Oh yes, absolutely.

C:

Could you give an example?

BDP:

It’s always been said that I don’t have good scenarios. For Act of Vengeance, the film I’m making,

I decided to hire a good writer. We’d work together, I’d let him write it and

we’d see what would happen. I think I’ve got a good scenario. Whether I can get

a good film out of it is another matter.

C:

Do you think there’s a contradiction between your way of making a film an d

good scenario? There’s always a difference between having a good scenario that

has to be illustrated and introducing more physical elements, as Hitchcock did.

It’s the same struggle as there was at the time of the New Wave when people

said “ good scenario doesn’t really matter.”

BDP:

It’s the old struggle between form and content, and for all

major stylists it dominates everything. Basically there are two possible

directions. On the one hand, the film is original because what I believe to be

its substance is its visual form. On the other, in a film like Carrie, I can indulge myself in the

most baroque style, but then I’m obliged to remain in the world of high-school

girls. That keeps my feet on the ground. I don’t drift off into a Ken Russell

type world where there’s no real or emotional basis to hang onto and where he

just has to float. I’m not against that, but the problem is that in breaking up

the narration you forget the audience. I used to be a great fan of Godard, but

I find it difficult to see his films again now. From the point of view of

styles what he’s done is very good, but it’s like cubism. When you break the

form down you realize there’s something odd about it – at least, I do. Can you

really hang these paintings up in your house and live with them? Or do you say

to yourself “It’s a fabulous, amazing idea, but now I’d like something that’s a

bit closer to me.” From an intellectual point of view what he does is very

powerful, it’s a bit like Eisenstein. Some of his films were marvelous, but I

never watch Eisenstein movies at home. I prefer Howard Hawks. There’s always

seems to be struggle between genius and stylistic innovation on the one hand

and the essential ingredients of story-telling on film on the other.

C:

By the way, Godard is one of your fans. He told us two years

that the only recent American film he had seen recently was The Fury.

BDP:

Yes, I know. I read that somewhere. I’ve always admired Godard a lot. I was

absolutely bowled over by Weekend

[1967]. But when his films are being shown I don’t make any effort to go and

see them.

C:

Maybe that’s because a lot of what he invented or created has been copied and

become commonplace.

BDP:

Exactly. D.W. Griffith is another example like Eisenstein and Welles. When you

study film you go see their work and are surprised. But their films are not the

sort you would have at home. Citizen

Kane [Orson Welles, 1941] isn’t shown all the time.

You

can fast-forward others and study scenes that you particularly like, but from a

purely emotional point of view I don’t find this be as effective as The Searchers [John Ford, 1956].

C:

Don’t you think that during his English period and for part

of his American one, Hitchcock had a kin d of golden age when it was possible

to work on style without losing the primitive and popular aspects of his films?

One of the reasons why Cahiers are

increasingly interested in your work is because you’ve kept some of that

without copying or plagiarizing Hitchcock, you’ve tried to keep the same

quality of being simple and basic in you style and in what you produce. This

seems to be just about unique in the American cinema today.

BDP:

Yes, but at the same time Hitchcock was a consummate

businessman. He’d exploited television before people realized its potential

importance and he made a lot of money. As far as I’m concerned the key to the

American film industry is its capitalist side. We can admire what the French,

the Italians or the Germans are doing, but it’s not us, and I think that when

we try to copy them it’s disastrous. Over here we make cars, sewing machines

and mixers, and we work and sell on grand scale. It’s like that and I don’t

think we should change.

C:

But like Hitchcock you’ve got this very pessimistic

philosophy that goes with this idea – this English idea that there is something

sinful about business.

BDP:

Basically I think that, in spite of everything that has been written about

Hitchcock, when he sat down and thought about the film he was going to make, he

said to himself “Will it really be interesting? Will it scare them? Am I going

to get them?” It’s as if he was saying “Are they going to buy this Ford?”

That’s basically how he thought of his films. Critics and university people can

say what they like about the Catholic symbolism in his films. What really

motivated him was “How can I make ten million dollars with one million?” In my

view, that’s the American system. As far as style is concerned, Hitchcock never

lost sight of the ultimate object of the film. I put all my craziest ideas

about style into Carrie, but I never

forgot that it was about a girl who absolutely hated her fellow pupils and

killed everybody. That was what drove the film. I think the problem for the

independent director is that he says to himself “Shit! Shit the studios! Shit

the public! I’m an artist and what I want is to enjoy myself.” Maybe he can do

that, but perhaps no one will want to see his film – and in the American system

it’s very difficult to get over that because we live in world where you have to

succeed. People read Variety not the Cahiers du cinéma. That’s the world we live in. How many people are interested in

what’s happening in the back of beyond? Everyone says “Pauline Kael gave me a

good review, and I couldn’t care less what the population in some God-forsaken

place is doing,” but it’s not quite true. I think what really matters is the

number of people you want to attract.

C:

Why do you live in New York rather than in California?

BDP:

The problem with California is that you’re right in the

middle of this industry and you don’t have the necessary distance from it. I

think economic imperatives dictate to a certain extent what you want to do but

they shouldn’t dominate. In Hollywood they are too prominent. You are always

being examined and judged to see where you are at, how much your last film

made, what your next one is going to be. And it has an effect. You start to say

to yourself “Perhaps I ought to make Barbara Streisand’s next movie.”

C:

When I saw Red

[Warren Beatty, 1981] recently I felt that audiences are increasingly taken in

by American films less and less. They don’t manipulate them or trap them any

more. That, for me, is style – games. And the more this happens the more I feel

the cinema is loosing something vital. But this refusal to play the game –

which comes from Godard or Straub – is already something. But Reds is neither one nor the other. It’s

like the pages of book being turned.

BDP:

That’s just another example of the effect of capitalism on the artist; he

becomes his own bank. We don’t have artistic sensitivity one the one hand and

commercial sensitivity on the other any more, we have the two at once. That’s

why there are so many directors who’ve run out of steam at the age of forty,

like Bogdanovich and Billy Friedkin. What’s happened? They’ve made a few good

movies and now they make these odd films that have no interest, not even an

aesthetic one. It’s sad. I often think about that.

C:

Do you feel isolated?

BDP:

Not really. I’m still trying to hit the jackpot. I still want to have the kind

of huge success we we’ve been talking about.

C:

Apart from Cassavetes and a few others like you, there are

very few filmmakers who succeed in showing the pleasure they have in making

films.

BDP:

I think in some ways you can see in John and me the absolute happiness there is

in trying to find the money to a movie!

C:

And what’s more, you often show people who are in film or

who are interested in technique like the kid in Dressed to Kill or Travolta in Blow

Out. It’s like a mirror that reflects the pleasure of working at technique

in film – like sound, for example.

BDP:

Yes, were only too happy to be filmmakers. We don’t have the feeling that it’s

a heavy burden to communicate with humanity. I don’t have the feeling I’m

writing The New Testament each time.

C:

Don’t you have projects that you dream about but you’ve never been able to

realize?

BDP:

Yes, of course. Act

of Vengeance for example, the film about the murder of the Yablonski

family. I’ve been trying to make that for seven years. Most of my projects take

three or four years. For me, it’s never easy. Perhaps that’s what’s saved me.

C:

What has an experiment like Home Movies meant to you?

BDP:

That was always a disappointment. I tried to teach in a

college how to make small budget films like I did fifteen years ago. We made a

film and had a lot of difficulty in finding a distributor; it didn’t go well

and it was never widely shown. It’s always the same story. The students

probably learned more from the fact that it wasn’t a commercial success than

they would have done if it had been hugely successful.

C:

You made it at Sarah Lawrence College where you made your

first film, and it seems that there are lots of things that are like those in

your earlier films.

BDP:

Yes. They have a lot in common. Except that the first film was made in 1963-4

and the second in 1978-9. What’s dreadful is that exactly the same thing

happened – it was a commercial flop – but it was a valuable experience. What

surprised me was that I made the movie for $300,000 and nobody in the film

world bothered about it. My reputation wasn’t much use, apart from getting a

few extra meetings. And I can say that it was ten times worse than before. Ten

times! I had the idea when I went into universities with different films. I

would ask the students who the directors were of the films they were going to

see, and they looked at me wide-eyed – they didn’t know a single one. So I said

to myself, who are these people? Maybe they need a course on small budget

films. After that a few of my students went on to make small budget films and

that’s good. But it made me realize how difficult it is –worse than I had

imagine.

C:

Among those of your films that have not been successful are there any that you

prefer?

BDP:

Hi, Mom!, for example. At first it

was shown at Loew’s State in New York, the worst place you could find for this

film, because the distributor thought it was one of those anti-establishment

films, which was not the case at all. It was a very strange film. Phantom of the Paradise was billed as a

rock opera extravaganza and it made no impression on the rock world, or the

horror film world – in fact on no-one.

C:

In Paris it enjoys a kind cult.

BDP:

Yes, I know. And my biggest disappointment is Blow Out. It was brought out in the middle of summer as an

adventure and action movie. It was shown at a bad time and in a thousand

cinemas. It’s an unusual political film, full of meaning and very carefully

constructed, but it didn’t do well. I was stupefied when critics said it was a

bad suspense and horror movie. Nobody understood it. Audience didn’t like

either the character played by Travolta or the film. In the United States the

distribution cost were eight million dollars or so, which is disastrous for a

film that cost so much. I avoided developing the love story in this film

because I didn’t think the character would be interested in it. But that’s what

the public expects it seems when you have John Travolta and a pretty girl If

I’d made more of the fact that he falls in love with her and by mistake puts

her in danger maybe the film would have been more successful. I hesitated a

great deal but thought that that wouldn’t interest him. He was only interested

in what obsessed him and his problem was that he always relied on his skill to

solve his difficulties. That’s more or less how I see people. With the trio of

John Travolta, Nancy Allen and Brian De Palma that film cost eighteen million

dollars, but if I’d made it for five million and with unknown actors it would

have been better. The various bits of the film didn’t match my ideas, at east

from an economic point of view. I could have realized my idea for four million.

I didn’t need all that show and fuss. It’s a typical example of capitalist

excess. I can make a big action and adventure film, but it’s not right for this

story. It wasn’t made for that. It’s rather an intellectual reflection on the

Watergate climate.

C:

Let me ask you a question about Obsession, which is the film of yours that I prefer. I’ve heard it

said that Paul Schrader felt a bit betrayed by the changes you made to his

scenario. Is it possible tot say that he felt just as betrayed by the work of

Bernard Herrmann? According to what I’ve read this film can be considered a

three-way collaboration between you, Herrmann and Schrader.

BDP:

When I’m preparing a film I put everything on cards and I

build up sequences like that. When I did it for Obsession there was a whole third part that didn’t work. It only repeated what had happened in the

past by projecting it into the future and it was no longer in what Paul

Schrader called the cut version that finally appeared. And when I laid the film

out I said “We’ll never manage this third part, the public won’t understand.”

I’d already thought that. When Benny read the scenario he said “That’ll never

work,” which only confirmed what I felt. And my suggestions didn’t please

Schrader. He said it was only the ending that gave the film any value and if we

took it out we would have a kind of television melodrama. It was big mistake

and I was pathetic. And then I read that he had said that I had ruined his big

project. In my opinion Obsession works, and Taxi Driver [Martin Scorsese, 1976]

works. None of Schrader’s films work because when he is left to himself he

can’t sort out his structural problems. It’s when you have directors like

Martin Scorsese or me who know how to get something worthwhile out of these

stories that they are successful. I’ve been rather bored by this business, but

I hope his flops will make him realize that he is not the structural and formal

genius that he thinks he is. It’s another example of a director’s megalomania.

I remember, when he showed Martin and me a tape of Hardcore [Paul Schrader, 1979] we suggested a lot of changes, and

the film came out more or less as it was on tape. There was a period in our

lives, or perhaps because we were poorer, when we listened to what was said to

us. We appreciated constructive criticism. Unfortunately that’s no longer the

case today. The only ones who are still open to this way of working are George

Lucas and Steven Spielberg. It’s unbelievable what Steven and I passed on to

George for Star Wars!

C:

Do you show your films to Lucas and Spielberg?

BDP:

The last time I did was with Home Movies.

But the problem is that we live in very different places. That’s what

success is: you run all over the world. Lucas and I are planning to make a film

together with Spielberg, and that would be good. This collaboration between

directors is something I miss, and Steven is one of the few who are open to it.

Me too. We all started like this in the early 1970s, but we don’t do it any

more. It’s a shame.

C:

After Phantom of the Paradise, which

I like a lot, are you tempted to make another musical comedy?

BDP:

I’ve thought about it. I like that, but nobody has really made a successful

rock film. Rock-and-roll had a powerful influence and there must be a way of

using it in a movie. It’s one of my ideas.

C:

What do you know about your public?

BDP:

You have the public of your successes. Movies that work create a public for

that kind of film. When I make films like Carrie,

The Fury or Dressed to Kill a certain number of people come to see them. But

when I make something different like Home

Movies or Blow Out again I think

I would do it differently, because I think have lost some of my audience. It’s

the same for Phantom… I thought that

Dressed to Kill would be demolished

by the critics because of its similarity with Psycho [Alfred Hitchcock, 1960], but, on the contrary, I received,

one of the best lot of reviews of my career. I was really surprised.

* Act of

Vengeance was eventually made for TV by John Mackenzie (1986).