Cahiers, on the other hand, throughout its history, since 1951, has gone through over 11 chief editors. The magazine was founded by Joseph-Marie Lo Duca, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and André Bazin. The magazine’s format, and spirit, was built upon the earlier La Revue du cinéma that began in 1928 and was founded by Jean George Auriol, who would die in a car accident in 1950: Doniol-Valcroze would dedicate Cahiers to the memory of Auriol. Then Bazin, “incontestably the best critic on the cinema” and an important figure early on at the magazine, died of leukemia in 1958. Serge Daney, the intellectual backbone of the post-68 Cahiers years, and who would go on to found the journal Trafic, died of AIDS in 1992.

Not only do these deaths strongly impact the magazine, less drastic, but not necessarily less intense, the changing of order at the magazine, has created ruptures between the writers of the different generations, and with it a shift in the magazine’s editorial line, sometimes modest, and other times, radical.

***

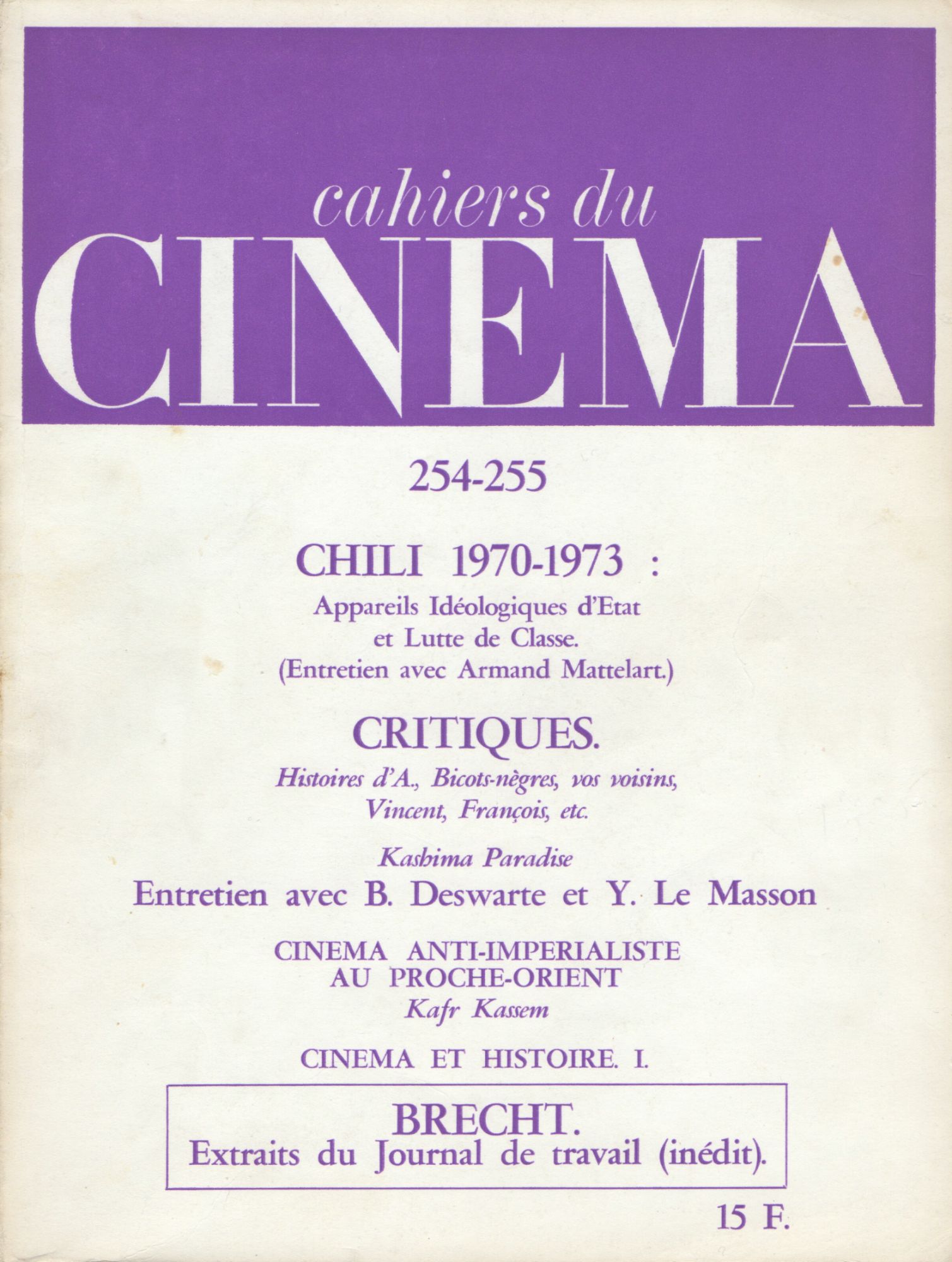

There is also the relation between Cahiers and their publisher that needs to be taken into consideration. Though there is a marked shift in 1964 when the publisher Filipacchi purchased the magazine: the famous yellow covers changed and they became more modern (bold colors + title + film still) and there were many new important writers like Narboni, Vecchiali, Skorecki, Daney, Biette, Téchiné and Comolli (who would become the editor the following year). A more radical shift occurred in 1969 when Cahiers divorced from Fillipacchi: they stopped publishing for three months, before resuming, where there was a marked politicization and stronger interest in theory. By 1972, they have removed the film still from the cover, and in that year they only published five issues, which would be the average for the next few years. During this time Serge Toubiana joined the magazine, and with Serge Daney, they would slowly redirect the magazine towards films. By 1976 a new format would emerge, which would allow for pictures, and they would slowly write more about contemporary film releases and less about theory and overt politics.

There is also the relation between Cahiers and their publisher that needs to be taken into consideration. Though there is a marked shift in 1964 when the publisher Filipacchi purchased the magazine: the famous yellow covers changed and they became more modern (bold colors + title + film still) and there were many new important writers like Narboni, Vecchiali, Skorecki, Daney, Biette, Téchiné and Comolli (who would become the editor the following year). A more radical shift occurred in 1969 when Cahiers divorced from Fillipacchi: they stopped publishing for three months, before resuming, where there was a marked politicization and stronger interest in theory. By 1972, they have removed the film still from the cover, and in that year they only published five issues, which would be the average for the next few years. During this time Serge Toubiana joined the magazine, and with Serge Daney, they would slowly redirect the magazine towards films. By 1976 a new format would emerge, which would allow for pictures, and they would slowly write more about contemporary film releases and less about theory and overt politics.

To cite the year 1978 (N.284-295) as an example, here is some general information about what they produced that year:

The covers included (in chronological order): Marco Ferreri’s Rêve de singe, Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux, Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story, Francois Truffaut’s La Chambre Verte, Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses, John van der Keuken’s Herman Slobbe, L'Enfant Aveugle N° 2, Peter Handke’s La Femme gauchere, Hans-Jurgen Syderberg’s Hitler: A Film from Germany, John Cassavetes’ Opening Night, Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois, and Adolfo G. Arrieta’s Flames. It should be noted that just because a film still was used on an issue’s cover, it did not necessarily mean that there was a review of it in that issue, sometimes they would only appear in a few issues later.

The January 1978 issue opens with an editorial that is signed by Daney and Toubiana, "For two years now, Cahiers du cinéma has returned to its regular publication, which is that of a monthly. This regularity constitutes the base and is indispensable for the life of a magazine, to its continuation, and regarding its future projects." Prior to this, between 76-77 the magazine had to deal with a financial crisis and administration problems. The two writers, in the editorial, further explain their hope to enlarge the readership of Cahiers, and in the next issue there is a change of design, "a layout with more space, and a mise en page that is more adequate for the actual content of the magazine," with a shift from 68 to 76 pages.

During this year some impressive texts include: an obituary Trois Morts (Chaplin, Hawks, Tourneur) and a review of Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind both by Jean-Claude Biette, Paul Schrader on Ozu, an interview between Nicholas Ray and Bill Krohn, Louis Skorecki’s famous text L'Ancien et le Nouveau: Contre la nouvelle cinephile (which seems to represent the end and the beginning of two separate forms of cinephilia).

In an interesting interview on Comparative Cinema, Jean Narboni is interviewed about a 30 year Cahiers anniversary film program that he curated for the Cinémathèque Française, Narboni writes,

“Regarding the idea of the hinge, for me the 1981 program marked the end of a cycle. At that time I was unaware of this, but it signaled the end of something. When the season began, Giscard d’Estaign still ruled France, and by the end, the Left and François Mitterrand seized power. Cahiers's 30 years closes a period. The 1980s bring in an institutional left, defined by the interests of the parties, of the government, that doesn't have anything to do with May 68 and its aftermath. In contrast, the program included all the periods of Cahiers, including May 68.”

***

In Charles Tesson’s editorial’s Raccords et accrocs (May ’01, N.557), he brings up the social history of the magazine in a discussion of a Cannes-Cahiers film program,

“It will retrace the history of the magazine, its engagement with cinema, its choices, from one extreme to the other, and especially the sentimental history of those that created it. Because Cahiers, it is also a long history of transitions between generations, sometimes gently (with good relations), sometimes aggressively (with unfixable tears between people). There is an effective history of Cahiers, which is that of everything that has been said and written about the cinema, but also an affective history of Cahiers (how writers enter the magazine, how they reach out towards the older writers, how writers leave the magazine without really doing so, content or injured).”

Regarding the new twenty-first century magazine format of the magazine, Tesson would write in the editorial Va savoir (Oct. '01),

"With this issue, the new formatting of Cahiers is one year old. With each new month, our concern consist of creating all of the different sections (Événement, Le Journal, Repliques, Entretien, Cinéma Retrouvé, Cahiers Critiques) and to also create, evident and hidden, connections between them, so that the different sections speak to each other, affirmatively or through contradictions. "This new formatting, would be revised slightly over the next decade, to improve its mise en page. There is now, after the table of contents and editorial, an emphasis given towards the features that are closer to the front of the magazine. So this clear and direct hierarchy proceeds: Événement, Cahiers Critiques, Le Journal, Cinéma Retrouvé.

In late 2009 when the art publisher Phaidon became the magazine's new publisher and Jean-Michel Frodon passed the magazine over to Stéphane Delorme (who has been writing at the magazine for almost ten years, and whose first review was Snake Eyes), in this last editorial Frodon wrote about the transition, “Cahiers is fifty-eight, it has changed ten times, it is great and vital that it keeps changing. To change to remain the same Cahiers.”

From all external appearances this transition was amicable. Since then Cahiers has steadily become one of the best film magazines. The magazine's cover switched from film stills to a new graphic design to be able to highlight its Événements. Delorme has refined the magazine's editorial position so that it is clear and critical (cf. Programmer, Margins at the Center). The Événement section regularly publish dossiers on unexplored territory of cinephilia (cf. Cahiers and James Gray). The Cahiers Critique section usually offers three to five must-see "films of the month." The Le Journal section has vastly improved and has become a space to discuss the "Cahiers films" in a different form.

***

To return to the idea of fissures at Cahiers du cinéma, the following is one of its significant rifts, and is necessary to bring up, in a serious discussion of the history of Cahiers. In a previous issue, the partnership with Le Monde was marked to be an "important date in the history of Cahiers." And then, in a few issues later, the May '99 issue (Cahiers, N.535), with a still from Pedro Almodovar’s All About My Mother on its cover (a film that Tesson would analyse as being about the cinematic experience, a trope of the period, along with referencing Samuel Fuller and Luis Buñuel), there would be a break-up between two of its major writers: Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana. To illustrate the importance of these two writers, de Baecque would go on to write the major Cahiers reference, a two-tome history, and has recently published books in English on Tim Burton and Camera Historica, about cinema's relation to history. And Serge Toubiana was the Editor in Chief of Cahiers for over twenty years and is now the artistic director of the Cinémathèque Française.

The letter (which I translated below) was at the very front of the issue and is titled Je t’aime, moi non plus. In it the co-editor of the time de Baecque explains why he is leaving Cahiers and Toubiana offers a rebuttal. The transition towards Le Monde was an important step in the improvement of Cahiers' graphic design and mise en page. Since then the published writing in Cahiers have at times gone in both directions and these letters speak to the questions of the complexities, difficulty and politics about writing about cinema. - D.D.

*****

Why I'm leaving Cahiers

I decided to leave my job as editor in chief of Cahiers du cinéma and to not write in the journal for a while. This decision arises from a disagreement with the director of the Cahiers, Serge Toubiana, which is the reason for this divergence, something that happens in the life of all magazines. We no longer share the same vision and solutions to the identity crisis that the magazine has been experiencing since the mid-nineties. In light of these interrogations, Cahiers' first order of business, is to respond to its economic concerns: this is why its new publisher will be Le Monde. I think that everyone at the magazine was in agreement on this point. This isn't the reason for our disagreement but instead lies in other questions: What should Cahiers look like to best respond to its proper crisis, to regain its dynamism, rebuild its image and their credibility, and to win new readers?Our disagreement, between myself and Serge Toubiana, was born, at least from my point of view, from an uncertainty regarding the immediate future. The admission of failure: the policy of the opening editorial of the journal, which I had lead, and that I felt was likely to be able to renovate Cahiers, and to attract more readers, did not happen as I would have wished. Other reasons, in short, internal skepticism and sometimes incomprehension. The ideas was an opening editorial and approach based on the model of the Cahiers from the sixties, and to be open to other types of writing on the cinema (philosophy, literary, artistic), another actuality (not just have to only follow the reductive format of highlighting the films of the month), and to follow other interests (history of cinema, contemporary art, cinephilia, politics, new world cinema).

The aim for all of these essays would be to better nurture readings of contemporary films and provide breathing room within these pages where the criticism has been too cramped.

My fear about the immediate future was then to draw out an alternative format for the magazine which was intensified in these last few weeks by the change of owners and the preparation of a new format. Is this a film journal or only a film magazine? During the discussions about this new formatting, I have always refused the second term of this alternative, to instead propose a project that, in its substance and in form, would allow for the coexistence (radically) of the vivacity of a journal (that would take the example of the Journal des Cahiers from the eighties) and the identity of a magazine that, for nearly fifty years, offered a way of thinking about the cinema. Today, I fear a form of "magazination" of Cahiers, which would destabilize its identity, without being able to renew its force and originality. To become a magazine (even a good and well done one) that provides a commentary (even if it is critical) about all of the new contemporary released films and cinema in general seems to me a real danger. And I don't think that this is what its current director wants either. It will be great for Cahiers if I'm wrong.

It is in taking account of these facts and these fears, that I realized that I can no longer have the means to help "renew" Cahiers. On a side note, these two last years for me as the Editor in Chief of Cahiers, however much was it hard work sometimes, was such an extremely rewarding experience. For this, I would like to thank the team, its writers, and the readers of Cahiers. - Antoine de Baecque

***

Response to Antoine de Baecque

Antoine de Baecque has decided to quit his role as the Editor in Chief of Cahiers du cinéma, a role that he has held since October 1997. His departure represents a crisis that was created through internal discussions about the essential orientation of Cahiers, which, by the way, has never prevented him to exercise his functions in total liberty. But this admission of failure that he evokes in his letter is equally my own fault, because we could not pilot this project together. In regards to this "divorce," the responsibilities will continue to be shared, and I will take up the necessary duties.

Our principal disagreement is regarding the essential critical orientation. In actuality, we were no longer on the same wavelength, once he started to advocate too much on a strategy that opened up towards other forms of writing on the cinema (literature, other arts) as a substitute for a real critical function. I still continue to think that this is the base of a magazine like ours, and not instead to pursue the question of taste for "new forms of writing about the cinema," a conception that prioritizes the triumphs of the literary or the specialist.

There was in the direction proposed by Antoine de Baecque a kind of cultural and sociological derivative (with the credo "the cinema as a cultural practice"), which is not consistent with the axis that has always been a priority for Cahiers. As for his implicit concern of a return to the past, a folding of Cahiers that will end up cancelling itself out, I hope to reassure him by saying that I will continually to aggressively champion, at the heart of a editorial team that will reinforce this, for a real critical passion that will foster more curiosity towards cinema, in all of its different forms, and to stimulate thought. Whatever the vagaries of a magazine like ours, it is this spirit that will continue to animate us. - Serge Toubiana

Antoine de Baecque has decided to quit his role as the Editor in Chief of Cahiers du cinéma, a role that he has held since October 1997. His departure represents a crisis that was created through internal discussions about the essential orientation of Cahiers, which, by the way, has never prevented him to exercise his functions in total liberty. But this admission of failure that he evokes in his letter is equally my own fault, because we could not pilot this project together. In regards to this "divorce," the responsibilities will continue to be shared, and I will take up the necessary duties.

Our principal disagreement is regarding the essential critical orientation. In actuality, we were no longer on the same wavelength, once he started to advocate too much on a strategy that opened up towards other forms of writing on the cinema (literature, other arts) as a substitute for a real critical function. I still continue to think that this is the base of a magazine like ours, and not instead to pursue the question of taste for "new forms of writing about the cinema," a conception that prioritizes the triumphs of the literary or the specialist.

There was in the direction proposed by Antoine de Baecque a kind of cultural and sociological derivative (with the credo "the cinema as a cultural practice"), which is not consistent with the axis that has always been a priority for Cahiers. As for his implicit concern of a return to the past, a folding of Cahiers that will end up cancelling itself out, I hope to reassure him by saying that I will continually to aggressively champion, at the heart of a editorial team that will reinforce this, for a real critical passion that will foster more curiosity towards cinema, in all of its different forms, and to stimulate thought. Whatever the vagaries of a magazine like ours, it is this spirit that will continue to animate us. - Serge Toubiana

+Sophie+Goyette_re%CC%81alisatrice.jpg)