DD: What is your background? How did you

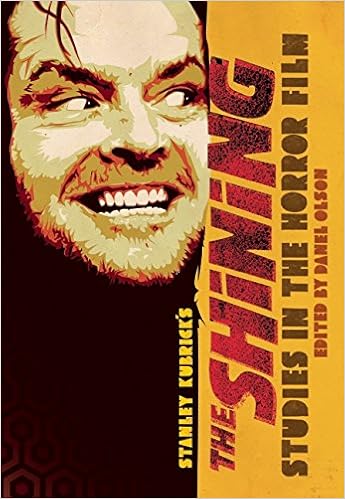

get involved with the Studies

in the Horror Film: Stanley Kubrick's The Shining [Centipede Press, 2015] book project?

What was your role in the making the book?

JB: I interview film-makers/actors/actresses for a living. I've

written for such print publications in the past as Fangoria and Videoscope,

and at present am a featured contributor with the long-running Shock Cinema magazine. I also

"blog" full time. I do interviews for several different

film/television websites all owned by one mega-company based out of Michigan. I

blog out articles and interviews on a plane of film/television topics which are

credited to my name and done anonymously as well.

I came to work

on The Shining book in late 2012,

when Jerad Walters, the owner of Centipede Press approached me about wanting to

re-print an interview that I had done with Shelley Duvall from late 2009. Prior

to Jerad reaching out to me, I had just finished conducting about twenty or so

interviews with various members of the cast and crew of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) for a

project I was interested in putting together about the film, but that eventually

fell by the wayside. I had mentioned my 2001

interviews to Jerad one afternoon over the phone, and out of that, he asked me

to contribute as many interviews as I could come up with related to The Shining for his book project.

As for my

involvement in the book... Basically, I did all the interviews that are

included in the volume, except those with Leon Vitali, The Burns twins, and

Diane Johnson. I did a share of the research for the project. I found the

previously published interviews for the book with Jack Nicholson, Scatman

Crothers, and the director of photography John Alcott as well. I had to track

down the rights holder for the Alcott interview. I hit all of my interview

subjects up for unpublished materials, memoriums, speeches, photos etc… Out of

that I found those never-seen Greg MacGillivray photos from the set, a couple

of pictures belonging to Ray Andrew – that amazing Maze panorma. I sourced all

kinds of vintage essays and magazine articles on the film across various

outlets, I found other interviews with cast members etc... I'd find them, and

I'd send them over to Jerad. From there, I imagine all the stuff I sent in went

to the editor of the volume. I was also supposed to write an essay on the film

itself, but I got overworked with tracking down people, scheduling interviews,

my own research into the film for the interviews, the hype of Room 237, etc... So I abandoned my

essay on the film. I have about 4000 words that I've done about the film, but

I'm saving my piece for now. I might do something with it in the future, but

for the time being – frankly, I'm just a little tired of The Shining.

DD: What is your essay about regarding The Shining?

JB: Let's talk about the essay at the end of this. It will give the interview a good

wrap-up.

DD: How many times have you seen The Shining? And what Kubrick resources do you really like?

JB: I was counting early on in the project, but, for whatever

reason I stopped. I can tell you that I watched the film, at least, once a day

for six-to-seven months straight. My resources for this project? I think all

the books that have been written about Kubrick to date are really solid,

well-written books. I think one can take a little from each that they read. But

I would advise those who have an interest in Kubrick to stay away from John

Baxter's biography however. That book is riddled with errors. In fact, as I was

researching the film, I would listen to John Baxter's commentary track on one

of the most recent Warner Brothers DVD releases of the film; and on that,

Baxter states something that is ridiculous – yet it took me down a weeks-long

rabbit hole when I first heard him say it. Baxter says, and forgive my

paraphrasing here: "Kubrick chose to use the numbers 2-3-7 in The Shining as an homage to Dr. Strangelove (1964) as they were the

same numbers that were supposed to disarm the bomb..." When I heard Baxter

say that on the DVD commentary, I freaked out. I think it was right around the

time that Room 237 had been

released. I was interested in the idea because of how much attention 2-3-7 had

gotten in Rodney Ascher's film, Room 237.

I decided to explore the idea because I thought, maybe, that if I brought that

bit of information out in the book through an interview it be would this

amazing factoid that would discredit Ascher's film in some stupid way. See,

when I first saw Room 237 I was not

a fan of it. I just thought it was ridiculous. I'm like most people, I'm of the

school of thought that if you put forth a theory about something you need to

have some evidence to back it up. And I didn't see the participants in Room 237 as having any real creditable

proof to support their claims. It seemed, at least to me, that Ascher's film

just managed to capture these incredible, almost, unbelieveable coincidences. It

really made me think of something writer Norman Mailer once said, and I think

he was paraphrasing Shakespeare when he said it: "Out of drama comes great

coincidences..."

In pursuing some

evidence to back up Baxter's claim, I went back and re-watched Dr. Strangelove. Now, I've seen Strangelove at least thirty-times. So,

I know that there is no visual reference to 2-3-7 in the film itself nor is

there any dialogue mentioning those numbers. Thanks to a archivist friend I

managed to get my hands on the shooting script for Strangelove. I opened that, and of course, there is no mention of

2-3-7 in there either. So that led me to read the book that the film was based

on, Peter George's Red Alert. There

is nothing in there pertaining to that number, of course. I read Peter George's

novelization for the film too. Guess what? – There is nothing in there to support

Baxter's claim either. Out of frustration, and hoping to just get an answer in

my search, I emailed John Baxter directly. His response? "I don't

remember." I searched for a couple additional days for connections. I

cross-checked 2-3-7 with military communication codes, I checked the numbers up

against number theory, even numerology as well. There was nothing whatsoever

that connected 2-3-7 with Dr.

Strangelove. I really think that Baxter just made it all up for the

commentary.

DD: I'm glad you brought up Room 237. I wanted to ask you about it anyhow. What makes this book so special

is how it reacts against things that are in Ascher's film. The analyses of the

documentary – from the scene of Jack Nicholson reading the Playboy magazine,

the geography of the set, and its other hypotheses – are discussed with its

creators, who usually think that it goes too far...

JB: Yeah, well, as I already mentioned, I didn't like Room 237 on my first-viewing of it. I've

since seen it a few times, and I admire it now as a film for its aesthetic

approach. I do think Rodney Acher's a brilliant film-maker. I'd be going too

far to suggest that Ascher's re-invented the documentary as we know it for the

zeitgeist, but he has certainly re-defined it aesthetically. It's just too bad,

that in doing that, he's been completely overshadowed by the subject matter of

his film though. I, frankly, for one, am so sick and tired of documentary films

about movies or makings-of about the making-of. They all seem to blur together

for me, and they all take the same aesthetic approch. One thing everyone is

guaranteed to see in any of the recent documentaries to come out in the last

three-four years about any film or rock band – it's that moment where an image

appears on screen with that reverse zoom. There's an image, in color, then it

goes to freeze frame. The image then

turns to black and white, and whatever the subject of the image is – a person,

let's say, then, that person is cut out of the background and we always get

that slow reverse zoom. The figure in the image slowly moves closer to us. You

see it in every single documentary that is made today practically. That's what

I loved about Room 237. I loved that

it changed up the entire approach to documentary in a sense. Ascher's film is

really great because of how it strived to not just be about these theories in

relation to The Shining, but that it

strived to exist on a different aesthetic plane in it's presentation. I know

many people bitched and complained about how they felt it was confusing because

of the fact that one doesn't see any of the "talking heads" in the

film, but I found that profound because of what it does to one psychologically.

If you're really

asking me about whether I agree or adhere to any of the ideas in Room 237, I will say that I do not. But

that doesn't mean that they don't hold any merit. I mean, those theories or

ideas or whatever you wanna call them--those are those peoples' truths and realities.

Film is completely subjective, right? Hell, all art is really subjective. It's

what makes the film critic, or the notion of film criticism completely null and

void of merit itself. Some of the ideas in Room

237 are interesting for sure. There isn't enough time to talk all of the

theories in Room 237, so let's just

talk about the (alleged) American Indian connection. Am I interested in the

idea that The Shining may be some

sort of allegory about the atrocities upon the American Indians? No, I'm not. I'm

not, because there isn't enough evidence to support the theory, and every thing

in Room 237 that is pointed out in

reference to the Blakemore theory can be explained away with ease. I feel like

in my interviews in the book, one should get a good idea of Kubrick's working

method. By understanding this, one should be able to shake off the ballyhoo of

the idea of the American Indian imagery in The

Shining as having some secret meaning...

To start, if you

read The Shining volume, one knows

that Kubrick sent a research team out across the Southwest of the United States

to take photographs of many hotels for research for the film. The "Red

Bathroom" in the film was copied from a bathroom that one of the research

team saw in Arizona. I believe it was at The Biltmore hotel there – if memory

serves... We know that the research team visited the Ahwahnee Hotel in

Yosemite, California. Have you see photos of the inside of the Ahwahnee ever? I

mean, even today, some thirty-odd years after they visited it, it has almost

the same decor inside of it. It is just covered in American Indian imagery. The

red elevator doors, with the black lattice surrounding them that we see in The Shining film – that idea was taken

from the mens' bathroom there at the Ahwahnee. One need only read the

interviews with Les Tomkins and Brian Cook in the book, to understand how

Kubrick was adament about virtually duplicating what he saw in his research

from the States. He liked the visual aesthetic of the hotel, so he duplicated

it for The Shining – indian imagery

and all. This is certainly consistent with what, I believe, is suggested in Jon

Ronson's wonderful documentary Stanley

Kubrick's Boxes (2008) from a few years back. In that documentary, one of

the researchers on Eyes Wide Shut

(maybe Manuel Harlan?) talks about how Kubrick wanted him to take photographs

of nightstands in the bedrooms of the apartments he was visiting. Apparently he

was fascinated by the layout of the items on the nightstands? I believe he said

something like: "You could never create that same arrangement on the nightstand

of those items ever..." In one of my interviews in the book (maybe with

Brian Cook?) something similiar is discussed regarding the Overlook hotel

design/motifs: "Why would I try to design something like the hotel, when

the original is much more interesting..."

In addition, the

notion of the Indian imagery also appears early on in Stephen King's book as well.

Anyone who has ever said that "the book is so much different from the

film..." has never read the book carefully or read it at all. Over the two

years that I worked on this book project, I read King's book ten times. When

the Torrences arrive at the Overlook for the first time in King's book, King

notes how there are Native American masks adorning the walls of the hotel. In

Kubrick's thirty-forty page treatment of the novel, there was an early idea

where Danny, in one of his visions, sees one of these masks spewing out green

flames. Kubrick felt that his film was very faithful to King's book, and I for

one, agree with him. I think if one goes back and re-reads King's book

carefully, and doesn't treat it like the "page-turner" it is, one

might notice the many subtle ideas on the page and how they may have influenced

Kubrick. One easy example to point out: The idea of the maze appearing in the

film. People often city the inclusion of the maze in the film as being one of

the elements added by Kubrick to the story, but in fact, if one goes back to

King's book, one will read about every ten-twelve pages about how, and

sometimes King does it in half a sentence, but usually at the end of a chapter:

"...the hotel was maze-like..." or "...the corridors of the hotel

twisted..." or something like that. I'm paraphrasing again, of course. But

it's totally there in the book.

The elevator

appears in the book. The weird dog-faced man who felates the well-dressed gentleman

appears in the book. As an appartion, the dog-faced man confronts Danny in the

book in one of the hotel corridors one afternoon saying – almost verbatim – Nicholson's

Three Little Pigs line from the

film...

Yes, Kubrick did

shift around certain narrative-points of the story. Yes, he cut out sub-plots.

Yes, he changed the ending. But, these are things that any screenwriter would

do on his own. These are things that any director would do. But, it's such a

point of contention for many, as if in some ways it reduces the merit of the

film in some way. It's crazy. I think Kubrick was right in his approach to the

film. He "trimmed the fat," as he said in some interview around the

time of the film's release. And rightly so, it's a terrible book, in my opinion

anyhow. What's the addage? Good books make bad movies? Bad books make good

movies?

While Room 237 is aesthetically wonderful as

a documentary, for me, it's a dangerous film as well. One thing that I really

took from it, an element that I think is wonderful in it – it reminds one of

the importance of a discourse about any work of art, right? But, it's dangerous

too, because of its audience being the internet generation. The first time I

saw Room 237, I walked out saying,

"Great, now all of these hipster kids are gonna go around telling people

that they think that The Shining is

all about the atrocities inflicted upon the American Indians." Because our

culture revels so much in film-as-entertainment, and not film-as-art (no matter

how much it claims to be for the latter), we don't want to have to think about

what we see. We are spoon-fed information and we often times accept it with

open arms. If one spends five minutes on Facebook, and visits any number of the

several Stanley Kubrick Groups, one sees those riddled with Shining/Indians

references. Search Facebook for a

hashtag "#TheShining" and see hundreds, well, maybe not today, but

last year hot on the release of Room 237

– "The Shining is really about

the atrocties of the Holocaust or the American Indians..."

Yes, Kubrick was

interested in a element of the American Indians appearing in the story! But as

an allegorical device? I don't think so. I think he understood, through his

research, the idea that he needed a guise to implement the supernatural into

the narrative. There's that, plus there are the elements in King's story too,

as I've already mentioned, however spare. And, of course, the hotel SK was

duplicating was grounded in Indian imagery as well. One plus one plus one

doesn't equal one hundred, it equals three.

DD: What I like about Studies in the Horror Film: Stanley

Kubrick’s The Shining are all its

interviews. It’s like the Ciment book, which had some good interviews, but this

book goes a lot further, by interviewing a lot of the periphery characters in

the film. I was wondering how it was to find all of these interviewees? And do

you have any other cool stories from the experience?

JB: If I told you, then I might be out of a job in the future.

Other cool stories? I have so many stories that I cut out of the interviews. I

had to cut some stuff at the request of the interview subjects, and Centipede

Press also cut a thing here or there on the advice of their lawyer as well. My

favorite experience? I have two... The first:

Just this general feeling in the air that I felt during the interviews. As

a Kubrick fan you've heard all of these stories about how brutal he was... How

meticulous he was... How crazy he was... Yet, his crew – he worked with almost

the same crew members film-after-film-after-film. That should tell you right

there exactly what his crew thought about him, and what he thought about his

crew! His crew loved him. So, in talking with many of the crew members, one

could feel in the air that there was still this great sadness swirling around

above, even all these years later, that he was still very missed. In fact, one

crew member I interviewed, when we got around to talking about SK's passing,

began to cry. I could hear tears in his inflection. That got to me.

Another moment

that got to me, perhaps, more than any other, was when I spoke with one of SK's

cameraman on The Shining. This

particular crew member, when I first called him to inquire about a interview

turned me down. He thought that I was only interested in talking about Kubrick,

the crazy, eccentic guy that the media has grown quite fond of reporting about

over the years. Which, of course, I wasn't interesed in doing. This crew member

and I ended up talking for well over two hours one Saturday morning over Skype,

and at the end of it, after having talked for those two hours about The Shining and Kubrick, his favorite cameras,

his favorite lenses, etc… The crew member said to me, completely

out-of-the-blue and unprovoked: "You know, Justin. I'm sorry you never got to meet Stanley. He

would have really liked you..." And when he said that to me, I got choked

up. It really made me emotional. And for what reason? I mean, what is it about

Kubrick that would cause me to have such a response?

DD: Was there anyone that you wish that

you could have included? I was wondering why the assistant director Michael

Stevenson, Stanley’s daughter Vivian Kubrick, and the executive producer Jan

Harlan weren’t included?

JB: Absolutely, in fact, there were many people that I spoke

with in-passing that I wanted to talk in-depthly with but, for one reason or

another, wouldn't commit to a time to talk. I exchanged many, many emails with

little Danny Lloyd, now grown-up, a teacher out East. We went back-and-forth

for months and he just wouldn't commit to talk to me, yet, near the end, he

graciously granted an interview to some little UK online website. Jack Nicholson,

I reached out to, and his Manager got back to me but in the end decided wasn't

worth his time. A friend of mine, a well-known screenwriter, actually gave

Nicholson's phone number, but in the end, damn – I was just too scared to call

him. I just didn't want to call him unsolicted. I also exchanged many, many

emails with The Shining Costume

Designer Milena Canonero – but she was always tied up with work to talk with

me. I got in touch with The Shining

Assistant Director Terry Needham, Camera Operator Danny Shelmerdine, Shining

composers Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind, Richard Daniels, one of the soundman

on the shooting of the film. Lou Bogue, a grip on The Shining. All declined

participation for one reason or another. I tracked down one of The Shining

electricians even. He was so busy with work that he could never commit to a

time to talk with me as well. I even pursed an interview with the Star Wars producer Gary Kurtz. Kurtz

had been a Borehamwood during the shooting of the film. He was there with

George Lucas waiting to start Empire

Strikes Back (1980). Their production was delayed start a few weeks, I was

told, because of The Shining. I was

told by a source that Kurtz and Kubrick had it out a couple times because of The Shining delaying the shooting of Empire Strikes Back at the studio. But

I never got to confirm this with him directly.

Sadly, too,

there were some involved in the film that I reached out to as well, that just

couldn't talk with me because of illness. One actor from the film was too ill

as was one of the crew members. Pivotal people in the making of the film, that

may not be with us much longer. I never reached out to Jan Harlan, as Centipede

Press informed me early on in the project that Harlan had declined

participation but that he wished us luck with the project. Michael Stevenson, I

spoke with briefly on the telephone. He also declined to participate as he said

he was instructed not to speak with me about the film because of another book

in the works about the film. Vivian Kubrick? I reached out to her, and I also

reached out to Kubrick's other daughter Katharina Kubrick as well. I heard

nothing back from either, nor did I hear back from Christiane Kubrick either

when I emailed a request for interview. There were others too, whom I'm

forgetting now in this moment as well. I reached out to everyone that is still

alive. I even reached out to the African American model who was the subject of

the nude painting that we see hanging on the wall of Scatman's apartment in the

film. I found her on Facebook. We exchanged a few messages, and in the end she

wanted financial compensation to talk to me.

DD: The interviews offer fascinating,

varying and sometimes even contradictory perspectives on Stanley Kubrick and The Shining. These interviews are helpful to understand the film but do you think

they demystify the aura around it as well?

JB: Not really. Maybe. I don't know actually. I was always more

interesetd in demystifying the Kubrick mythos than I was in trying to do such

relating to film itself. Any questions that hint at Room 237 theories, really came up because that film was out and

circulating and it was on everyone's mind that worked on The Shining. The crew members would often bring it up in our

conversations. One might say: "Did you see this rubbish?" I think the interviews do a decent job at

breaking some of the tabloid notions associated with Kubrick, and yet, they

also add to them as well...

DD: What are your thoughts on the ending

deleted scene of Danny in the hospital? I think that it’s really important and

I wish that that footage was still available. Just from the description it

seems like it almost anticipates Eyes

Wide Shut – the secret society, the

brainwashing and controlling of women and children, and the banal menace.

JB: I like the way the film ends now. The hospital footage is

out there. I know of someone (allegedly) who has it here in the States. Maybe

someday it will surface or then again, maybe not. SK didn't want it to be seen,

so as someone who is faithful to the artists intentions – I'd like to respect

his wishes.

DD: Two areas of interest for me

regarding Kubrick are his connection to the moon landing footage and his

relationship with Steven Spielberg. I find the William Karel documentary Opération Lune to be really convincing. And I don’t care what Leon Vitali says,

Kubrick was a very private person, and it could have been a secret that he

worked more closely with NASA. While the Steven and Stanley documentary shows the two as being good

friends. What are your thoughts on these subjects?

JB: I think Opération Lune (2002) was a joke,

wasn't it? Isn't that the documentary with Donald Rumsfield in it? I am

one-hundred percent certain that Kubrick had nothing to do with the

moon-landing. His connection to NASA came out his friendship with Arthur C.

Clarke. I've always thought that Jay Weidner from Room 237 has probably just watched Capricorn One (1977) one too many times...

DD: I really like the Emilio D’Alessandro

interview. How were you able to get in touch with him? Have you read his book Stanley e me? Is it only available in Italian? And the Joan Honour Smith interview,

about the retouching of the final photograph, is really great. How did you go

about to find her?

JB: I have a friend, a great guy, who runs this incredible site

in Italy dedicated to 2001: A Space

Odysssey. I think I got in the door there through him, if memory serves. From

there I just called Emilio up and we spoke one evening. I believe, that yes, Stanley e me is currently only

available in Italian. I actually suggested to Emilio that he contact Centipede

Press about publishing the book in the United States but I don't know if

anything came out of that suggestion. Joan Smith – she was a lot of fun to talk

with. She was actually pretty easy to find. The challenge, initally, was

finding out who had done the photographic work on that picture in the film. But

once I found that out, she was very easy to find online.

DD: Are you happy with the final product?

Or was there anything else that you wished that you could include?

JB: I am, yes. Actually, I got into a spot of trouble when the

book arrived to me back in June, as I had forgotten to include my wife's name

in the acknowledgements. When she opened the book and saw that her name was missing

she wasn't very happy. She said: "I watched that movie with you every

night for months!" I think that Jerad Walters at Centipede Press did one

hell of a fantastic job with the design and the layout of the book itself. When

I got the galley from him back in December of '14 to review it so I could

suggest edits I was really impressed with the design of it even back then in

its raw presentation. I really wished those that those, who declined interviews

with me, would have participated however... What could've been will always be a

question in my head I think...

DD: And what about your essay on the

film?

JB: Well, I am almost hesitant to talk about what it's about,

but I will, I guess. The thing that has eluded almost everyone regarding The Shining is Kubrick's aesthetic

approach to the film. For Kubrick, all of film was a dream. In fact, if you

pick up the great book that Alexander Walker did on Kubrick at the start of the

'70s, Kubrick tells Walker: "to me, all film is a dream..." So with

that mind, one can free themselves up to explore the film through that lens. Considering

how fascinated Kubrick was with Freud and Jung – in particular, Freud's The

Uncanny – in relation to The Shining,

it stands to reason that we can explore the film even deeper through the guises

of the Freud and Jung, even their dream modules. In particular: Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams and Jung's Man and His Symbols. Using those books

we can look at visuals in the film with the idea that the visual cues serve as

symbols for subtextual context in the film itself. An example of this: So much is made in Room 237 about the non-sensical appearance of Shelley Duvall

reading J.D. Salinger's The Catcher in

The Rye in The Shining, and how

it is really a weird choice for inclusion into the mise-en-scene itself as in

the prior sequence in the film with Nicholson at the hotel he tells Stuart

Ullman that "..his wife is a confirmed ghost and horror story

addict..." Again, forgive my paraphrasing there... Yet, when we consider

the core of the narrative in relation to the moment in which this information

is relayed to us, we know that Jack Torrence has hurt Danny in the past, right?

He's come home, one evening, having had too much to drink and injured Danny – pulling

his arm out of his socket. As a dream symbol in the film, Salinger's The Catcher in The Rye serves a very

potent visual cue to suggest to us, the audience, Shelley's state-of-mind. We

know, from reading The Catcher in The

Rye, that one of the major aspects of its narrative is this notion that

Holden Caufield must protect the children's innocence. When, you consider this

idea in Catcher in The Rye

juxtaposed up against the mise-en-scene with Shelley sitting at the table

reading the book, her cigarette ash growing and growing (another visual dream

symbol) – Kubrick is communicating with us visually the unconsious

state-of-mind of Wendy Torrence. She is terrified within the familial unit. The

unspoken, natural bond that is constructed within the family unit between man

and woman and their child – it's been forever tainted by Jack Torrence's

drinking and violence toward his son. She is terrified for her son's safety

from the start of the film itself. This, of course, being one of the most

important aspect of the story to Kubrick – if we are to read closely, his

interview with Michel Ciment from 1980....

There are so

many "dream symbols" in the film itself. Whether Kubrick researched

them or allowed them to come to fruition out of instinct – we'll never now. I'll

leave it up to anyone that might read this to explore this idea farther. I

have, in my essay, about forty or fifty well-marked dream symbols in the

film.

The most potent

dream symbol in the film is the vision of the elevator of blood. People should

really look to that as a visual cue up against Freud and Jung interpretation...

It's quite staggering when you consider it in the context of the

narrative.

DD: What new projects do you have in the

works?

JB: Thanks for asking. Right now, I'm finishing up a year of

work on a sort of experimental print anthology about the films of Pulitzer

Prize-winning writer Norman Mailer. Mailer produced some very polarizing work –

three films in the 1960's, a film in the '80s, and a slew of scripts that he

wanted to make but didn't get a change to get off the ground before the end of

his life in 2007. Mailer was a big supporter of the avant-garde cinema. In the

'60s he helped finance the films of Robert Downey Sr., and Ron Rice. His

written works are layered with film metaphors even. Film was very influential

upon him, and he wrote some pretty incredible theory stuff in the late '60s – in

the spirit of Eisenstein and André Bazin. His films are amazing because they

mix theatrcality with Dostoyevsky, film noir, Godard, and Cubism.

I'm also working

on a biography of film-maker Frank

Perry. I've been working with his estate closely for the last couple years on

it. They've been a great source of information and guidance. I've done about

100-120 hours of interviews thus far relating to Frank and his incredible

films. On The Shining book, I did

about 35 hours of interviews in total. I'm hoping to have the Perry book done

by late 2016. After that, I'm taking a very long break.