‘I related

to Davis Mitchell and to this journey.’ – Jean-Marc Vallée

‘On était jeunes. On était fous. La bohème, la bohème. Ça ne veut plus rien dire du tout.’ – Charles Aznavour

‘On était jeunes. On était fous. La bohème, la bohème. Ça ne veut plus rien dire du tout.’ – Charles Aznavour

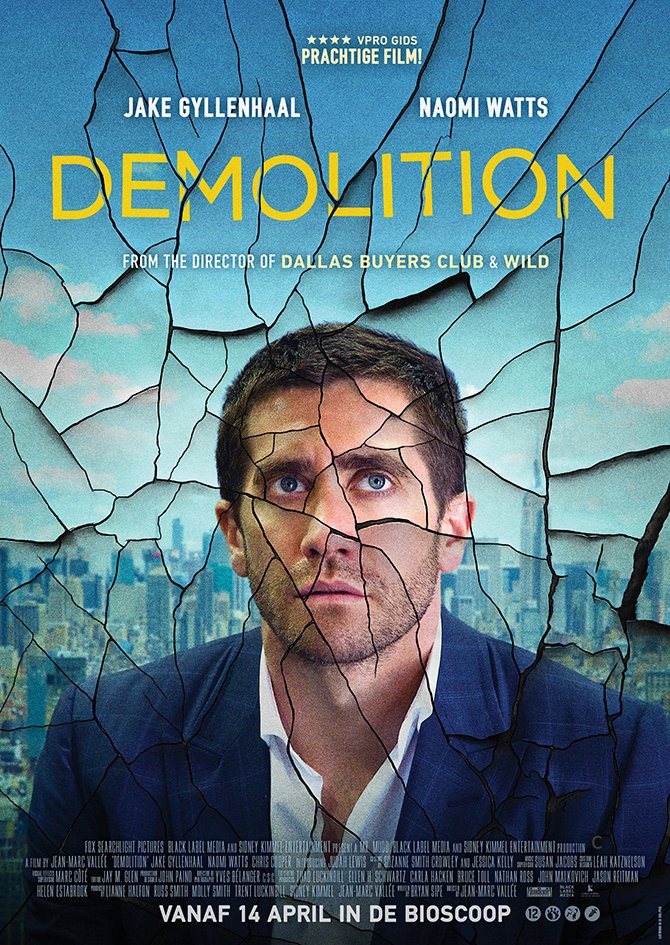

The release

of a Jean-Marc Vallée DVD is always a special occasion and with this new

Blu-ray of Demolition you can now

take the film home in its pristine image and sound quality. It’s the story of

Davis Mitchell, a successful Wall Street banker, and after his wife's sudden death

his life is shook up and through grieving he is able to find himself, learn to

feel again and start a new friendship with a single mother Karen and her son.

Every scene and detail in the mise en scène provides a unique rhythm and information that has a larger meaning in Demolition’s complex structure and Jake Gyllenhaal is perfect in the role with his subtle expressiveness and range. This expression of intimate human feelings is the emotional réel of the film that is given substance as it engages with the geographical réel. The scene that best illustrates this is when Jake Gyllenhaal dances through New York City, engaging with its landmarks and enjoys himself. This is the Valléeien gesture: that of in cynical times to bring music and joy to people and the city. These non-narrative scenes, that contribute and build on an emotion, are Vallée's specialty. Similar to Howard Hawks, starting with The Big Sleep and To Have and Have Not, Vallée likes to stall the storytelling to focus on scenes for the sake of creating good ones: where Hawks aimed for entertaining character development and witty dialogue, for Vallée it is that of a musical lyricism. This musical point is made explicit with the film’s soundtrack (only available as a digital soundtrack from ABKCO Music and Records, with a press release that reads almost as if it was written by Vallée) that ranges from classical, folk, indie pop, rock and electronica; and where each song gets to the heart and personality of each character without ever being too recognizable (Depeche Mode is another unidentified reference).

Vallée is able to create this musical lyricism with Yves Bélanger’s refined yet simple imagery that brings a palatable energy and emotion to each scene. While Vallé's regular cameo, that of a mourner at Julia's funeral, explicitly continues his humanist outreach project (which goes back to his role as the priest in C.R.A.Z.Y.) but is now turned towards the upper class, which is a similar gesture to that of Denis Côté with his Boris sans Béatrice. This fantasy and support for others leads to Mitchell’s phantasm at the end of Demolition where he’s reunited with the ghost of Julia (similar to apparitions like Raymond in C.R.A.Z.Y., Rayon in Dallas, and Bobbi in Wild) on the carousel that was reconstructed in honor of her legacy.

Then there's the Paul Valéry quote in Demolition and, as with Café de flore, Vallée seems to enchanted by the culture of the Paris of the belle époque and the melancholy and beauty of the popular poetry of its time. ‘The future is not what it used to be,’ which for Valéry when he wrote this in the thirties, meant that the atrocities of the Great War would taint the comforting assumption that the future will no longer resemble the past, but which Phil applies to the world of digital trading and unregulated capitalism. But another Valéry quote that would have been equally appropriate, for either the title or for Mitchell, is from the most recent Hayao Miyazaki film: “The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!” The idea of poetry as a privileged escape from the oppression of reality has currency for Vallée as language, style and new technologies are all equally important for him to express his poetic vision through his mise en scène. As Demolition takes language and ontology as its starting point: Mitchell tries to make sense of his existence by discussing his life, the mood and atmosphere, the meaning of words and the limits of his own psyche and his physical body. Underneath the surface of beings and objects lies an essence and this is what he's searching for. So Phil tells him, “If you want to fix something you have to take everything apart and figure out what's important,” while for Mitchell, “Everything has become a metaphor…” This is why Mitchell tears apart as much from his life as he can with his hands, tools and even a bulldozer everything from his appliances to even the infrastructure of his own house.

There are a few details from Demolition that stand out after repeated viewing: The reoccurring gecko (similar to the fox in Wild) is actually from the Dan Deacon and Liam Lynch video Drinking Out of Cups where Deacon, in a thick Long Island accent, rehearses some cynical statements. The use of this viral comedy video from 2006 that Mitchell and Julia bonded over earlier on in their relationship (probably a Bryan Sipe reference) is just like Demolition as just like Mitchell and Julia had a negotiated response to this video (turning its cynical Seahorse reference into a romantic one) Vallée takes what could have been a cynical drama and fills it with warmth, care and love.

Vallée is clearly a réalisateur d'oeuvre as with each new film he builds upon the previous one and all of them contribute to the world-building of his filmography: A Matthew McConaughey-like cowboy appears in a parking-lot in Wild, the business man that tries to pick up Cheryl Strayed at the end of the memoir spins off with Mitchell in Demolition, and the mother-and-son Karen and Chris will anticipate Jane and Ziggy in Big Little Lies. [In the credits there are also references to used footage from Wild from Twentieth Century Fox (though I can’t exactly pinpoint it; maybe the earlier hospital scenes?) as well there is the Snow Monkeys clips which Mitchell watches before going to sleep (from WNET/Thirteen Productions) which anticipates the snowstorm ending of Du bon usage des étoiles.]

Though the Blu-ray is skimpy of features, there’s at least one great one on it: the Behind the Scenes location footage of the production (mostly short scenes) which is mostly silent with some natural noises. There is Vallée carrying the camera, similar to Soderbergh, and he talks to the actors in his energetic English. There is the small crew, and all of the production specifics, as they’re out filming on naturally beautiful outdoor locations. This form of poetic and personal cinema, along with Vallée’s resourceful means and major actors eager to work with him, makes him closer to a filmmaker like Terrence Malick than to most other Hollywood independents. The other few making-ofs are short and not that impressive (e.g. rehashed footage from the film, with espoused clichés from the crew). So there could have been more… But, either way, it’s incredible to have the chance to re-watch Demolition and the Blu-ray looks and sounds great. It can keep any Valléeien occupied until the release of Big Little Lies on HBO next year. Mysteries are abound.

Every scene and detail in the mise en scène provides a unique rhythm and information that has a larger meaning in Demolition’s complex structure and Jake Gyllenhaal is perfect in the role with his subtle expressiveness and range. This expression of intimate human feelings is the emotional réel of the film that is given substance as it engages with the geographical réel. The scene that best illustrates this is when Jake Gyllenhaal dances through New York City, engaging with its landmarks and enjoys himself. This is the Valléeien gesture: that of in cynical times to bring music and joy to people and the city. These non-narrative scenes, that contribute and build on an emotion, are Vallée's specialty. Similar to Howard Hawks, starting with The Big Sleep and To Have and Have Not, Vallée likes to stall the storytelling to focus on scenes for the sake of creating good ones: where Hawks aimed for entertaining character development and witty dialogue, for Vallée it is that of a musical lyricism. This musical point is made explicit with the film’s soundtrack (only available as a digital soundtrack from ABKCO Music and Records, with a press release that reads almost as if it was written by Vallée) that ranges from classical, folk, indie pop, rock and electronica; and where each song gets to the heart and personality of each character without ever being too recognizable (Depeche Mode is another unidentified reference).

Vallée is able to create this musical lyricism with Yves Bélanger’s refined yet simple imagery that brings a palatable energy and emotion to each scene. While Vallé's regular cameo, that of a mourner at Julia's funeral, explicitly continues his humanist outreach project (which goes back to his role as the priest in C.R.A.Z.Y.) but is now turned towards the upper class, which is a similar gesture to that of Denis Côté with his Boris sans Béatrice. This fantasy and support for others leads to Mitchell’s phantasm at the end of Demolition where he’s reunited with the ghost of Julia (similar to apparitions like Raymond in C.R.A.Z.Y., Rayon in Dallas, and Bobbi in Wild) on the carousel that was reconstructed in honor of her legacy.

Then there's the Paul Valéry quote in Demolition and, as with Café de flore, Vallée seems to enchanted by the culture of the Paris of the belle époque and the melancholy and beauty of the popular poetry of its time. ‘The future is not what it used to be,’ which for Valéry when he wrote this in the thirties, meant that the atrocities of the Great War would taint the comforting assumption that the future will no longer resemble the past, but which Phil applies to the world of digital trading and unregulated capitalism. But another Valéry quote that would have been equally appropriate, for either the title or for Mitchell, is from the most recent Hayao Miyazaki film: “The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!” The idea of poetry as a privileged escape from the oppression of reality has currency for Vallée as language, style and new technologies are all equally important for him to express his poetic vision through his mise en scène. As Demolition takes language and ontology as its starting point: Mitchell tries to make sense of his existence by discussing his life, the mood and atmosphere, the meaning of words and the limits of his own psyche and his physical body. Underneath the surface of beings and objects lies an essence and this is what he's searching for. So Phil tells him, “If you want to fix something you have to take everything apart and figure out what's important,” while for Mitchell, “Everything has become a metaphor…” This is why Mitchell tears apart as much from his life as he can with his hands, tools and even a bulldozer everything from his appliances to even the infrastructure of his own house.

There are a few details from Demolition that stand out after repeated viewing: The reoccurring gecko (similar to the fox in Wild) is actually from the Dan Deacon and Liam Lynch video Drinking Out of Cups where Deacon, in a thick Long Island accent, rehearses some cynical statements. The use of this viral comedy video from 2006 that Mitchell and Julia bonded over earlier on in their relationship (probably a Bryan Sipe reference) is just like Demolition as just like Mitchell and Julia had a negotiated response to this video (turning its cynical Seahorse reference into a romantic one) Vallée takes what could have been a cynical drama and fills it with warmth, care and love.

Vallée is clearly a réalisateur d'oeuvre as with each new film he builds upon the previous one and all of them contribute to the world-building of his filmography: A Matthew McConaughey-like cowboy appears in a parking-lot in Wild, the business man that tries to pick up Cheryl Strayed at the end of the memoir spins off with Mitchell in Demolition, and the mother-and-son Karen and Chris will anticipate Jane and Ziggy in Big Little Lies. [In the credits there are also references to used footage from Wild from Twentieth Century Fox (though I can’t exactly pinpoint it; maybe the earlier hospital scenes?) as well there is the Snow Monkeys clips which Mitchell watches before going to sleep (from WNET/Thirteen Productions) which anticipates the snowstorm ending of Du bon usage des étoiles.]

Though the Blu-ray is skimpy of features, there’s at least one great one on it: the Behind the Scenes location footage of the production (mostly short scenes) which is mostly silent with some natural noises. There is Vallée carrying the camera, similar to Soderbergh, and he talks to the actors in his energetic English. There is the small crew, and all of the production specifics, as they’re out filming on naturally beautiful outdoor locations. This form of poetic and personal cinema, along with Vallée’s resourceful means and major actors eager to work with him, makes him closer to a filmmaker like Terrence Malick than to most other Hollywood independents. The other few making-ofs are short and not that impressive (e.g. rehashed footage from the film, with espoused clichés from the crew). So there could have been more… But, either way, it’s incredible to have the chance to re-watch Demolition and the Blu-ray looks and sounds great. It can keep any Valléeien occupied until the release of Big Little Lies on HBO next year. Mysteries are abound.