Title:

Monte Hellman: His Life and FilmsAuthor: Brad Stevens

Publisher: McFarland & Company Inc (2003)

Pages: 212

Price:

$47.31“

Likewise, in many ways all my films are autobiographical. This is partly because I believe that the only way to be universal is to be specific and personal, and partly because it's the only story I know and thus can tell.” – Monte Hellman

The seventy-nine-year-old director Monte Hellman recently completed his latest feature film

Road to Nowhere and it has been twenty-one years since his last full-length

Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out, though in 2006 he contributed the short

Stanley’s Girlfriend to the omnibus

Trapped Ashes. Whether receiving a Special Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival for

Road to Nowhere in 2010 or receiving a lifetime achievement award at the Whistler Film Festival in 2011, Hellman has always had a close relationship with the film festivals. The programmers, film-critics and cinephiles have always been the ones championing his work. Emmanuel Burdeau recently published

Monte Hellman: Sympathy for the Devil in one of his terrific interview series for the publisher Capricci to accompany the French premiere of

Road to Nowhere at the Centre Pompidou, while the Cineteca in Bologna in 2009 published a valuable study by Michele Fadda

American Stranger: The Cinema of Monte Hellman. Hellman started his career by studying Speech and Drama at Stanford and then completed his graduate work in Film at UCLA, and I quote, “the film that most made me want to direct was George Stevens’

A Place In the Sun.” He now teaches film direction at CalArts

On Hellman’s career trajectory, Brad Stevens writes in his terrific book

Monte Hellman: his life and films,

“It is impossible to say whether the vicissitudes of Hellman’s career shaped or were shaped by the director’s existential philosophy, but the fact that he has made not one film in the last decade while Steven Soderbergh has made at least ten tells us all we need to know about the kinds of art that are currently considered viable.”

After university Hellman did some theater work where one of his standout productions include

Waiting for Godot as a western with a Texas Ranger and Native Americans – Brad would quote passages from

Godot at the start of each chapter to accentuate Hellman everlasting state of waiting and the films continuation of the absurd tradition. Robert Lippert (who would produce two of Hellman’s films) purchased Hellman’s theater to turn it into a cinema, which is still running today as the

New Beverly Cinema. Hellman then worked for the American Broadcasting Company as an apprentice editor on the television series

Medic (1956) and he writes about his experience, “this was when I learned most of what I know about both editing and film directing.” One of his friends Roger Corman got him work at his company Film Group and it was there where Hellman made his first full-length feature

Beast From Haunted Cave in 1959. “I was present in the editing, that’s where I learned the rest of what I know about film directing, from seeing my mistakes.” And he describes the movie, “

Key Largo with a monster added to it.” The movies screenplay by Charles Griffith is a lot of fun and Hellman uses it as a base to create these moments of intrigue between actors and space especially through the use of glances. Even though Stevens’ does not see the film as personal and he does this by quoting Charles Tatum Jr. (who wrote the first Hellman book in 1989), “ trying to see

Beast From Haunted Cave as a personal film by Monte Hellman would be a form of pathological auteurism.” There are two versions of

Beast from Haunted Cave: a TV print that is 71m 56s and a theatrical print that is 76m 30s. The additions were part of the Filmgroup expansions in 1962 and 1963. Corman was stretching his films for commercial time slots to seal a deal with Allied Artists television, so Hellman expanded

Beast from Haunted Cave, Ski Troop Attack, Last Woman on Earth, and

Creature from the Haunted Sea. In the extended print of

Beast Hellman padded new sequences of narrative standstill and personal reflections, for example the protagonist says, “I like what I’m doing. I think that’s about as easy as you can take it.”

Stevens’ is able to articulate Hellman’s intentional sense of “stasis” in only a couple of brief additional scenes Hellman added to another director’s films in particular to his work on

The Terror (1963) with his ”precise use of camera-movement and cutting,” that contributes to “Hellman’s theme of transferred identity”. On Hellman’s aesthetic advancement, Stevens’ writes, “the Filmgroup expansions enabled him to create scenes whose functions was to stall rather then advance the narrative…

The Terror demonstrated just how flexible plot markers could be and how they need not lead to anything, but could simply function as free-floating signifiers.”

Hellman met Jack Nicholson working on Harvey Berman’s

The Wild Ride (1960), which is a movie the Hellman edited but whose editing is surprisingly credited to a William Mayer (“I don’t think William Mayer was a real person”). They then went on to collaborate together in four pictures

Back Door to Hell, Flight to Fury (both 1964),

The Shooting and

Ride in the Whirlwind (both 1966). The first two are the producer’s Fred Roos Philippines pictures.

Back Door to Hell was filmed before

Flight To Fury, which has a screenplay by Jack Nicholson (a homage to Houston’s

Beat the Devil) and it includes four of the same actors as

Back Door to Hell. Quentin Tarantino’s article on Hellman (

Sight & Sound, Feb. ‘93) aligns his films in a strong American anti-tradition that includes the masterpieces

Kiss Me Deadly, Taxi Driver, and

New Rose Hotel. Tarantino refers to

Ride in the Whirlwind as one of his favorite Westerns and posits that

Flight to Fury is the first of the great Monte Hellman picture.

Roger Corman produced

The Shooting with a script by Carole Eastman (

Five Easy Pieces), under the pseudonym Adrien Joyce, and the film was shot in Kanab, Utah by the Zion National Park. It stars Will Hutchins, Millie Perkins, Jack Nicholson, and Warren Oates (Hellman’s first film together).

The Shooting is an abstract work as its richness is in the subtext, in what isn’t said but in what is felt. Two guys pick up a girl and are off to find a man. Nicholson is a black-gloved gunslinger whose eyes hide under his high-crowned wide-brimmed black hat, he begins to follow them. Everything about this western is dark, tormented and austere especially as the girl never reveals her name or intentions or motivations. A child was killed. It is suggested that the woman is the mother out for revenge. The mountains look like hell. The last scene is sublime: it is filmed in slow motion, there are gunshots and Oates whispers his identical brothers name.

Hellman’s

Ride In the Whirlwind was shot by regular cinematographer Gregory Sander with a score by Robert Drasnin and a screenplay by Jack Nicholson, which was inspired by

Vittorio de Seta’s

Bandits of Orgosolo (1960). Robbers harmlessly steal very little loot from a stagecoach, they find a hanging man, there is little talking and a black westerner is in the background. Two opposing groups are in a state of accommodation with a dormant conflict looming. There is a disparate sense of atmosphere, especially as Hellman films people waste down and figures elude a sense of mystery and enigma that are never explained. Hellman’s stylistic decision to create a sense of disparity has a Bressonian quality whether it is through a close-up of a horse’s head or a following mule (an allusion to Balthasar) or through a rhythmic editing style.

Hellman’s early films have the specific quality of capturing Jack Nicholson as star-to-be. Before his mainstay in mainstream Hollywood, before Jack Nicholson became ‘Jack’ as introduced by Billy Chrystal introduced him at the 1993 Oscars. Jack Nicholson was just another actor, a good one, whose titles include

Five Easy Pieces, The Last Detail, One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest, Chinatown, and some art movies like

The Passenger and

The Shining. In the Corman-Hellman films you see the debut of a would-be-star with the face of an implacable dissatisfaction and a will of non-conformity. Just like Hellman’s cinema where main characters can depart in a passive and nonchalant manner, Stevens’ discards Nicholson casually, though poetically, somewhere in a footnote at the back of the book.

These films are also notable for the casting of the terrific Harry Dean Stanton, whether it is as the eye-patched Blind Dick with a red scarf around his neck or as a wolf-faced hitchhiker slowly moving across the United States. Harry Dean Stanton has been in too many great films as a supporting actor by too many great directors with his apotheosis role being the lead as a romantic loner in

Paris Texas. It is worth highlighting his efforts.

In Jonathan Rosenbaum’s BFI Modern Classics Monograph (a series edited by Rob White) on

Jim Jarmush’s Dead Man, Rosenbaum furthers a sub-genre: the

acid western. According to Rosenbaum,

acid westerns are,

“‘revisionist’ westerns where American history is reinterpreted to make room for peyote visions and related hallucinogenic experiences…both ‘acid Westerns’ and ‘pot Westerns’ depend on re-evaluation of white and non-white experiences that view certain counter-culture habits and styles in relation to models derived from westerns but where they differ most, perhaps, is in their generational biases, which leads them respectively to overturn or ironically revise the relevant generic norms”

The westerns typical East-to-West journey is no longer one towards enlightenment and conquest but one of a long stand still, leading to death. Jim Jarmush uses the term “

peripheral Westerns.” Though

Ride in the Whirldwind and

The Shooting have little to do with the indulgence in narcotics, they do revise what is typically expected from a Western as they are more existential fables.

Stevens’ dedicates chapters equally to what Hellman is doing between projects to the films themselves. These ‘In Between Projects’ chapters (they add up to 33 years of waiting) reflect projects Hellman was thematically attracted to, who were his many collaborators, and what movies he worked on (usually as an editor) among other things. Some information that is brought up is contradictory to general record whether it is Peter Bogdanovich claiming he edited part of Roger Corman’s

The Wild Angels though Hellman, who actually edited the film, says that that he didn’t. Hellman also edited Bob Rafelson’s

Head, though he is now uncredited, and he was supposed to make a movie about a black sheriff in the South, that was cancelled the day before filming.

.jpg)

Hellman is most known for his existential road-movie

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) with Laurie Bird, James Taylor, Warren Oates and Dennis Wilson with a screenplay by

Rudolph Wurlitzer (

Nog) and the cinematographer is Gregory Sandor (I have written more about the film

here). The film is about Driver and Mechanic as they pick up Girl in their Chevrolet 1955 as they move Southwestward from California racing G.T.O who drives a Pontiac GTO. Stevens’ describes

Two-Lane Blacktop theme, “that it is the inescapable fact of our ultimate demise which reveals how random contests of chance or skill function as substitutes for more meaningful action.” Hellman uses an interesting approach to actors in this film. He only gave them the script the previous night and as the shooting was in sequence, it meant, that the actors did not know what will happen until the previous night before shooting when they would get their script. Lew Wasseman, who was the head of Universal at the time, did not like the films producer Ned Tanen and gave

Two-Lane Blacktop a Fourth of July opening without any advertisement. It did poorly at the box-office.

Next up is the little-known

Shatter (1974) which was a co-production between England’s Hammer films and Hong Kong’s Shaw Brothers studio. It stars Stuart Whiman as the entitled character Shatter with a Don Houghton screenplay and John Wilcox as the director of photography. Hellman was fired after two weeks on the job as the producer was disgruntled. There is a LaserDisc with a director commentary by Hellman.

When talking to cinephiles about Hellman there are usually two of his films that immediately come up in conversation that captures the Hellmanesque beauty, exhistentialism and strangeness. These two films are:

Two-Lane Blacktop and

Cockfighter (1974; which was released on DVD by Anchorbay in 2000).

Cockfighter is based on a Charles Willeford novel with screenplay revisions by Earl Mac Rouch and Hellman. The great Néstor Almendros is the director of photography. In

Cockfighter, Frank Mansfield (Warren Oates) has sworn a vow of silence after his big mouth on a couple of occasions lost him his chickens and property. He is now trying to qualify for the Southern Cockfighting Conference Tournament. One night he stays with Judge Ed Middleton (Charles Willeford) at a hotel that is later robbed by Steven Gaydos wearing a Richard Nixon mask (Gaydos, is described as Hellman’s “most important collaborator”). Stevens’ describes one aspect of what makes

Cockfighter and Hellman’s art so indelible, “For Hellman provides the chickens with a wealth of meanings, working through a whole series of figural possibilities… but if Hellman’s film teaches us anything, it is surely the necessity of abandoning such reductive modes of thinking, where by behavior can be explained or explained away.” And the best description of

Cockfighter has been “chicken-sploitation”, which were in the liner notes to its

screening at the Mayfair Theater, Ottawa on February 26th, 2011.

Hellman worked on a pre-credit for the television network ABC version of

Fistful of Dollars (“While Leone’s protagonist had no name, Hellman’s has no head, face or voice!”) and he would re-make this introduction in

China 9, Liberty 37 and that John Carpenter would remake in

Escape from New York (1981). The producer Elliot Kastner gave Hellman a screenplay by Larry Cohen entitled

A Man for Deajum’s Wife, which eventually mutated into

China 9 Liberty 37 (a title that came to Hellman when he saw a sign with the postings on it). Hellman describes the working process as, “This is the only movie I’ve directed where we re-wrote the script as we went along.” As it includes a lot of inserted jokes, like the gag, “show him your nuts” and then Jenny Agutter sticks out her tongue to the man sitting on her right at the carnival.

China 9 Liberty 37 is a mixture of a euro-western like the

Django series and exploitation cinema as Fabio Testi, Warren Oates and everything else creates a potpourri of acting styles and situations, which show how commercial restraints can impede itself onto the art and affect the final product. The brilliant stylistic decision to use superimpositions will be further executed in

Stanley’s Girlfriend and small details like Warren Oates leaving the house to kill a chicken connects the film within the Hellman oeuvre.

Between 1978 and 1987, Hellman finished editing

Avalanche Express after the director Mark Robson died. He has a cameo in Michael Ritchie’s

An Almost Perfect Affair (1979), which was filmed at the Cannes Film Festival and also set at Cannes he tries to answer, “is cinema becoming a dead language, an art which is already in the process of decline” in Wim Wender’s

Chambre 666. While he also appears in Henry Jaglom’s

Someone to Love (1987). Hellman would direct,

Inside the Coppola Personality, which is a short documentary on the making of

One From The Heart. He married documentary filmmaker Emma Webster. While in 1982, Warren Oates died of a heart attack and in the book Hellman contributes a heart-felt eulogy, “He had a quality that hawked back to the great western actors like Gary Cooper, the silent man whose honesty and integrity were apparent from his face.”

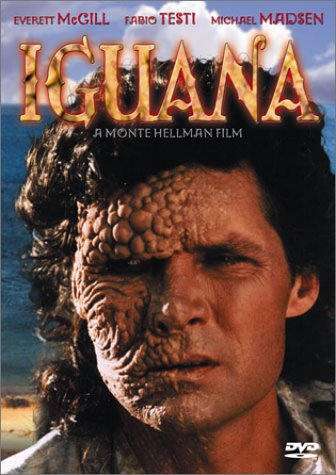

Iguana

Iguana (1988) is based on the 1807 real life figure Patrick Watkins who pirated in the Galapagos that was elaborated by Herman Melville in

The Encantadas, which inspired Alberto Vázquez Figueroa’s novel

La Iquana, which Steven Gaydos and David M. Zehr’s script is based on. The actors are Everett McGill and Fabio Testi and it was shot in Lanzarote, Canari Islands. Hellman discusses the difficulty of getting the project going and working with an uncooperative producer. The filming circumstances were undesirable as the lighting has yet to arrive and trouble ensued even with the small things like organizing a boat ride or just doing lunch. Stevens’ describes the problematic of the film, when Carmen’s experiences an orgasm while being raped by Oberlus, “Foreground those internalized power structures to which her behavior refers and of which we are all victims… Hellman does not explore the ramification of God’s silence, but rather accepts this silence as a given, depicting the world as an absurd place in which actions have no meaning… whereas Bresson repeatedly expressed his belief in transcendence, the concept has no meaning for Hellman who regards humanity as something to be celebrated rather than transcended.” Oberlus’ face after he sees the new-born child as “the silent equivalent of Laurie Bird’s “No Good” or Jaclyn Hellman saying “I am no good at games.” Hellman is a terrific creator of last moments and phrases as characters depart from the film. Just like how

China 9 Liberty 37 is dedicated to Hellman’s father who then recently passed away

Iquana is dedicated to Warren.

Hellman made

Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out (1989) for a producer friend Arthur Gorson, it is a made-for-TV horror film for Live Entertainment. It includes a lot of in-jokes (i.e. people watching

The Terror) and Stevens’ comments that “the feminist aspect of Hellman’s oeuvre tends to become clearer with each succeeding film.” Stevens’ quotes Bill Krohn’s

Cahiers du Cinema review of the film who writes, “for whom Newbury’s conflict with Connelly suggests a debate between two different attitudes to Hollywood’s sequel-mania… Newbury, who thinks he was right to awaken Rickey from his coma, wants the sequel to be made, while Connelly who would prefer that he hadn’t does not.”

*****The book

Monte Hellman: his life and films begins with two quotes. The first is by Jean-Luc Godard from

Two American Audiences and the second is by Gilles Deleuze from

The Movement-Image:

“Before World War I, Eisenstein and Griffith made completely different films, even though Eisenstein learned from Griffith. And Murnau in Germany and Chaplin in Hollywood – they all made different films. But it was all cinema. Where as the Eisenstein’s, Chaplin’s and Murnau’s of today are kept from doing films by people who demand a single universal cinema – which is a dead cinema.”

“The history of the cinema is a long martyrology”.

To expand on these thoughts, here are two other quotes by the same authors. The first is Godard’s manifesto from the press-book of

La Chinoise and the second is a larger batch of the paragraph from where the Deleuze quote originated.

“Fifty years after the October Revolution, American cinema reigns globally. There is not too much to add to this. Except at our modest level, we need to create two or three Vietnams at the breast of the immense empire Hollywood – Cinecitta – Mosfilms – Pinewood – etc… and, financially, aesthetically, its-to-say by revolting on two fronts, creating some national cinemas, free, of brotherhood, and of friends.”

“One cannot object by pointing to the vast proportions of rubbish in cinematographic production – it is no worse than anywhere else, although it does have unparalleled economic and industrial consequences. The great cinema directors are hence merely more vulnerable – it is infinitely easier to prevent them from doing their work. The history of the cinema is a long martyrology.”

These quotes resonates the ideological conflicts Hellman’s cinema has been at odds at for some time. On the screenplay of

Road to Nowhere, the films producer and screenwriter Steven Gaydos has said,

“I knew one truth about Hollywood… If I put another name on the list of possible directors, they would go past Monte to that other name. And I didn’t want to hear, ‘Oh yeah, Monte Hellman, a genius, a brilliant guy, one of the great American filmmakers, a poet, a fantastic talent, ‘Two-Lane Blacktop,’ a masterpiece. But don’t we have someone else more bankable?’”

The book includes an introduction by Hellman, an exhaustive note section, an annotated project list and filmography, behind-the-scenes pictures of Hellman, and a drawing of Hellman by Joe Sison. It is the history of a career. As Noel King at

Sense of Cinema has mentioned in

his own book review of

Monte Hellman: his life and films, “the book is, among other things, a triumph of e-mail auteurism.” Stevens’ wonderfully examines the effect of camera placement, angle of the frame, concession of scenes, acting, and noise. He quotes Roland Barthes and Robin Wood. And Stevens’ uninhibited enthusiasm for Hellman is admirable.

Over the years, Brad Stevens has created his own cannon of films (I first heard of Stevens from reading Rosenbaum’s

review of his Ferrara book), his own ‘Essential Cinema’, if you may, which does not look like any other list out there. He has written two books,

Monte Hellman: His Life and Films and

Abel Ferrara: The Moral Vision, and is a contributor to the print-publications

Sight & Sound, Video Watchdog (which is available in Toronto at Suspect Video) and the online site

Undercurrent. His writing only pops sporadically, though I am not too sure, I assume, it has do with either a lack of content he

wants to write about or a limitation of what he

can write about (Stevens’ also frequents the Dave Kehr

forums). While singular reviews might be of interest, what is truly fascinating is how they fit within a larger framework of film-appreciation. This framework comes across in the book and it leads to his helpful grouping of filmmakers, here is Stevens on ‘America’s marginalized filmmakers’:

“Hellman is only one (though certainly among the most important) of America’s marginalized filmmakers: Erich von Stroheim, Orson Welles, Albert Lewin, Nicholas Ray, John Cassavetes, Elaine May, Charles Eastman, Stanton Kaye, Sam Peckinpah, Donald Cammell, Michael Cimino, Abel Ferrara, and so on… All of them were to greater or lesser degrees victims of those financial institutions which theoretically exist to enable the production of films, but actually create obstacles for artist who refuse to conform with the dominant ideology.”

Stevens’ has also championed Spike Lee, James Toback, George Romero, and to include my own additions to the list of ‘victims of those financial institutions’ there is Todd Solondz - who in an interview in

Positif with Michel Ciment discusses the difficulty of financing and how he teaches at the NYU Grad Film program to sustain himself, and Whit Stillman - whose new film

Damsels in Distress is currently in production as it has been thirteen-years since his last feature. Stevens’ further elaborates on the

Road to Nowhere Facebook page, “As usual, all my choices [on his 2010 Sight & Sounds Top Ten list, which has

Road to Nowhere as number one] have pretty marginal distribution… It seems that serious cinema is now something that can only happen in the margins.” And I cannot help it, here is Stevens’ introduction to

The History of Cinema According to Monte Hellman which a piece he contributed to

Cahiers du Cinema (which included interesting observations on Hellman by Nicole Brenez),

“To begin with a proposition: Monte Hellman and Abel Ferrara are the most important working American directors. And if anything could be said to link these two otherwise very different artists, it is surely their lack of neuroticism, their ability, in a culture dominated by the life-denying obsessions of consumerism, to unblinkingly confront the beast in its lair without being captivated by its insidious charm. The result has, of course, been predictable, with Ferrara turning to Europe for financing, and Hellman, like Michael Cimino (now apparently retired from filmmaking), sentenced to increasingly lengthy periods of inactivity. As capitalism enters its crisis stage, it seems that the only position America currently deems permissible in its artists is that of fiddling while Rome burns, the most we can legitimately expect being the work of Friedkin or De Palma, who at least insist on fiddling with (to quote George Orwell's remark about Henry Miller) their faces to the flames.”

*****Roland Barthes’ discusses in his book

The Pleasure of the Text the notion of

semantic pleasures that arise from discovering new words while reading, I want to posit, that there are also

cinephilic pleasures, which is in writing the discovering of an unknown filmmaker or a positive assessment of a director that has been long dismissed. Stevens’ writing is full of these

auteurs. The ones that are either generally over-looked or ones that have received negative scorn critically or lack of visibility due to distribution, he flips those negative or non-perceptions by championing them, some examples, include Marco Bellochio, Otar Iosseliani, Theo Angelopoulos, and, more recently in the

Sight & Sound’s 2010 review, he champions Naruse Mikio, whose films, he highlights, are available online for free via the film-sharing websites like

karagarga.

In the book

Defining Moment in Movies (edited by Chris Fujiwara), Stevens entries include the Key Events; “Alfred Hitchcock sent to prison”, “John Cassavetes appears on the radio show Night People”, and “Jean-Luc Godard punches Iain Quarrier”; as well Key Scenes from the following films:

Gilda, The Postman always rings twice, Monsieur Verdoux, Ikiru, Lola Montes, I Live in Fear, Lolita, Lawrence of Arabia, The Leopard, Mouchette, Face to Face, Le Revelateur, Performance, Two-Lane Blacktop, To Die in the Country, The Story of Joana, Mickey and Nickey, Renaldo & Clara, The Shining, Bad Timing, Dr. Jekyll et les Femmes, Star 80, The Beekeeper, The Sicilian, The Caine Munity Court-Martial, King Of New York, Pulp Fiction, Vive L’amour, New Rose Hotel, Adieu Plancher des vaches, Water and Salt, Café Lumiere, and

The New World. Some reoccurring themes, from the book and in his writing in general, includes the chiding of “the overwhelming majority of ‘serious’ critics”, the inseparableness of style and meaning, personal projects, Hollywood’s representation of sexuality, social protests, and cinematic humanism.

Another thing that is impressive is the authoritative tone and lack of self-doubt (no, “I think”), clear articulation, and there is no necessity for him to have to defend his views. He does bother to contextualize some of these filmmakers: either you know about them or you do not. This is up to you. These qualities make Stevens one of those film-critics that cinephiles cherish as he communicates through writing what good film-criticism can be and of the possibility of what film can, and ought to, do.

*****

In the 400th issue of

Positif (“

Cinema seen by the filmmaker”) Hellman writes about his admiration of Víctor Erice’s

The Spirit of the Beehive and to describe it he quotes Jean Cocteau, “

Un oeuvre d’art devrait en meme temps etre un object difficile a saisir” [“A work of art must at the same time be an object difficult to grasp”]. A film Nestor Almendros, the cinematographer on

Cockfighter, recommended Hellman to see, he has now seen it more then a dozen times (another film Hellman greatly admires is Nikita Mikhalkov's

Slave of Love). Sometime Hellman receives scorn (and those guys are hacks), like here is a segment from a capsule on

Ride in The Whirldwind, “presented at the San Francisco Film Festival’s afternoon under the mistaken notion that Hellman’s lack of experience constituted a naturalistic style… what unreels is a flat, woodenly acted western with mild suspense.” What some film-critics do not see under this ‘flat, woodenly acted’ is its dreamlike wandering and existential aimlessness. It is about people in desperate situations that calmly accept their faiths and an exploration of the typical Hellman milieu. Hellman treats the characters with great sensitivity with acting that suggests ambiguities. And it is appropriate that the title of Hellman’s latest film

Road to Nowhere can be a descriptor of all the neurosis driven pursuits that came before them, which never got its hero anywhere.

Stevens’ elaborates Hellman’s fringe cinema-career as “the more restricted his credit, the freer he seems to become,” and, “Hellman’s cinema is a cinema of outcasts, of societal rejects who, however else they might differ, exist outside the mainstream.” Neither of his Westerns

The Shooting or

Ride in the Whirlwind had an American theatrical distribution until five years after they were made and Hellman’s masterpiece

Two-Lane Blacktop was released in the United States on the weekend of the Fourth of July with no publicity, doomed to fail –the studio hated the film.

Steven’s references an intertitle in Buster Keaton’s

The High Sign, “Our Hero came from Nowhere – he wasn’t going Anywhere and got kicked off Somewhere.” This is the cinematic lineage that Hellman will be incorporated in. Other masters include: John Huston (one of Hellman’s favorite filmmakers, “I guess every film I’ve made has either been

The Maltese Falcon or

Outcast of the Island”), Don Siegel (another director that started off being an editor), and Sam Peckinpah (who acts in

China 9 Liberty 37 and was also in Siegel’s

Invasion of Body Snatchers). Hellman acted with Jean Renoir in James Frawley’s

The Christian Licorice Store (1971).

And his influences are lasting on people like Quentin Tarantino (Hellman produced

Reservoir Dogs), Vincent Gallo (Hellman was supposed to direct

Bufallo ’66), Gus Van Sant, Hal Hartley, Win Wenders, Mika Maurismaki (Hellman appears in

L.A. without a Map), Jim Jarmusch and Terrence Malick. While contemporary directors that Hellman admires include Victor Erice (“of course”), Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Fatih Akin, Tsai Ming-liang, and his friends P.T. Anderson, Wes Anderson and Rick Linklater (who programmed

Two-Lane Blacktop at TIFF 2001). If you pay special attention in

Robocop you might see Monte Hellman in a brief cameo, where he was an uncredited 2nd-unit director. There are also two film documentaries on him Paul Joyce’s

Plunging on Alone: Monte Hellman’s Life in a day and Romuald Karmaker’s

Hellman Ride which are supposed to be quite good.

Since then Hellman contributed

Stanley’s Girlfriend for the omnibus

Trapped Ashes, which the Maples Pictures DVD includes isolated as a directors cut. The characters are Stanley (Tygh Runyan), Leo (Tahmoh Penikett), and Nina (Amelia Cooke). Everything takes places slowly, with a romanticisms. Jazz. In a long take, two guys have intellectual conversations within the setting of a b-film directors home. They play chess and the moves are both sexual and deadly. Overexposed lighting contributes to a dream-like quality. There is a moviola. Images of an unrealized Napoleon project. There are precise parallels to the life of Stanley Kubrick at the time that he was marrying the pretty brunette Ruth Sobotka, who he will divorce two years later. But there are also similarities between

Stanley’s Girlfriend and some experiences described in the Stevens’ book.

There has been much said about Monte Hellman from people like Quintin at

Cinema Scope Online,

Olivier Père who reviews Burdeau’s new

Monte Hellman book, the New York Times had a

piece on

Road to Nowhere, Olaf Möller praises

Road to Nowhere in his 2010 Venice Film Festival coverage for

Film Comment, an interview in

Filmmaker Magazine, Kent Jones has an essay

The Cylinders were whispering my name (

S&S Winter 70/71),

Dave Kehr reviewed

Two-Lane Blacktop when it was released on DVD by the Criterion Collection and Richard Combs, Richard Jameson and Peter Matthiessen have nice things to say about the guy.

As Tarantino said, “Movie theatres would be much happier places with a new Monte Hellman movie playing in them.” And as Stephen Gaydows graciously brought to my attention, the

Road to Nowhere Entertainment One Canadian release is set for May 2011, here is the

trailer.

David Davidson

.jpg)

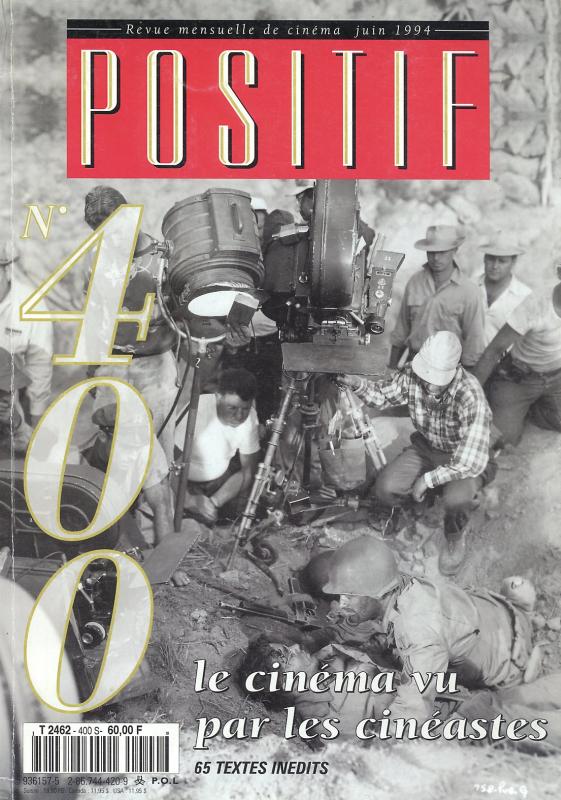

Paul-Émile Borduas, who was the head of the Automatistes, taught at L’École du Meuble until getting fired for publishing the group's manifesto Refus Global. With influences like André Breton, Paul Klee and Wasily Kandinsky the Automatistes would go and adapt the Surrealist maxim of “attempting to give pictorial form to the workings of the subconscious.” The groups formalism is best viewed as a variation of abstract expressionism. Refus Global in Québec was seen as a major provocation. The polemic supposedly lead to mine protest, which was already a desperate situation as seen in Claude Jutra’s Mon Oncle Antoine. Dénis Arcand would further examine worker dissatisfaction in On est au Cotton. These antecedents of left-wing Québécois directors and their radical and unruly spirit are at heart of the films of Denis Côté.

Paul-Émile Borduas, who was the head of the Automatistes, taught at L’École du Meuble until getting fired for publishing the group's manifesto Refus Global. With influences like André Breton, Paul Klee and Wasily Kandinsky the Automatistes would go and adapt the Surrealist maxim of “attempting to give pictorial form to the workings of the subconscious.” The groups formalism is best viewed as a variation of abstract expressionism. Refus Global in Québec was seen as a major provocation. The polemic supposedly lead to mine protest, which was already a desperate situation as seen in Claude Jutra’s Mon Oncle Antoine. Dénis Arcand would further examine worker dissatisfaction in On est au Cotton. These antecedents of left-wing Québécois directors and their radical and unruly spirit are at heart of the films of Denis Côté. The Scot John Grierson in the 30’s with his advocacy for the ‘documentary’ and the birth of the National Film Board of Canada led to a strict format of how to use the cinematic medium to convey facts in Canadian documentaries. And then in the ‘60s there was a loosening of this scripture with the emergence of people like Arthur Lipsett and Serge Giguère (see: Robert Daudelin and Jean Pierre Lefebvre articles on Giguère in 24 Images, No. 151), which prolonged into the ‘80s with the Morin-Dufour collaborations and into the ‘90s with Donigan Cumming. The emphasis was on creating new forms of storytelling through digging towards unexplored subjects, the layering of fact and fiction, an emphasis on video, varied running times and alternative viewing outlets.

The Scot John Grierson in the 30’s with his advocacy for the ‘documentary’ and the birth of the National Film Board of Canada led to a strict format of how to use the cinematic medium to convey facts in Canadian documentaries. And then in the ‘60s there was a loosening of this scripture with the emergence of people like Arthur Lipsett and Serge Giguère (see: Robert Daudelin and Jean Pierre Lefebvre articles on Giguère in 24 Images, No. 151), which prolonged into the ‘80s with the Morin-Dufour collaborations and into the ‘90s with Donigan Cumming. The emphasis was on creating new forms of storytelling through digging towards unexplored subjects, the layering of fact and fiction, an emphasis on video, varied running times and alternative viewing outlets.

.jpg)