Abstract

This essay will analyze

the Toronto DIY Filmmaker movement through studying some of its more prominent

figures and their work. Each filmmaker will be isolated (with the First

Generation filmmakers grouped together in their own section) and discussed in

regards to how they contribute to the representation of Toronto as a cinematic

city. There will be a focus in terms of their films, public activities, and

reception. Through studying the Toronto DIY filmmakers as a group hopefully a

broader sense of their diversity and preoccupations emerges, as it is through

their growing size that the movement stands out. Included would be a working

filmography. The introduction will contextualize the movement’s major themes,

stylistic approaches and relation to the Toronto New Wave.

Introduction

To broadly define the

Toronto DIY Filmmaker movement: Their

dominantly narrative films, shot with digital cameras, by young Toronto

filmmakers, about Toronto residents, set in Toronto. The origins of the movement can be traced back to

2009-2010 with the completion of Kazik Radwanski's MDF Trilogy and Matt

Johnson's Nirvana the Band. These

works are important due to the international recognition that they received,

groundwork they laid that led to their respective filmmaker’s future projects,

and larger local visibility that led to both Radwanski and Johnson becoming

public figures for the movement which since then led has led to the creation

and merging of a broader artistic community surrounding each of them.

The

methodology of studying filmmakers as auteurs in a Canadian context is argued

for by George Melnyk who writes, “Canadian

cinema is director-driven… The reasons for this are rooted in Canada’s cultural

history as a colony, as well as its tradition of state support for cinema that

ends up emphasizing directorial accomplishment.” For Melnyk, who defines

Canadian cinema as being integral to Canadian culture, the work of these auteur

filmmakers reflect the Canadian cultural psyche in terms of nationality, race,

gender, ethnicity and class. Melnyk argues that the Canadian film director has

risen to the status of a cultural icon, and that, “The auteur director has been

integral to the Canadian cinematic imagination and has served as its prime

foundation.”

The

emergence of the Toronto DIY filmmakers parallels other new national and

generational filmmaking movements that were taking place around the world. For

example, the

magazine Cahiers du Cinéma around

this period had a feature, New York: La

Génération ‘Do It Yourself’, in their September 2011 issue, where they

interview a range of up-and-coming independent New York filmmakers. As well the

Québécois magazine 24 Images proposed

a similar conceptual framework in their discussion of a ‘New Québécois

Generation’ of filmmakers, which from this group Denis Côté has been an

important influence on the Toronto DIY Filmmakers, regularly seeing each other

when he would bring a new film to TIFF, he would provide a model of a festival

filmmaker and offer constructive criticisms to some of them. Many of the issues

surrounding filmmaking and how to represent their respective cities in both of

the aforementioned magazines were simultaneously occurring in Toronto, which

for these Toronto DIY filmmakers meant that they were starting to get notice

from the Toronto-based film magazine Cinema

Scope who would highlight some of their work.

The

Toronto DIY filmmakers offer a youthful, fresh perspective on growing up in the

city – childhood and schools are an important feature of them and so is being a

young adult – and they offer a unique look on specific parts of Toronto’s

urbanism and geography. The year 2010 is important for the movement because

these filmmakers would have experienced the first decade of the 21st

century in Toronto while also allowing for a temporal rupture with the previous

one as they could start tabula rasa on

how to conceptualize the city for a new decade.

An

important aspect of the movement is that it is do-it-yourself, which means that it excludes major productions and

films with major funding (including those by more privileged young filmmakers).

The freedom of being in charge, and having to work for, deciding on the content

(however modest or crude), form, distribution is integral to this group. These

DIY filmmakers typically use non-professional, non-ACTRA actors and

technicians, and they do not work within the industry or with its unions. The

rise in prominence of digital

filmmaking equipment has been a great resource to these filmmakers, as perhaps

were it not have been available, they might not have been as productive and

unconventional as they are. Also of importance is how with the technological

developments of many of these new digital cameras, which the Toronto DIY

filmmakers have relatively easy enough access to (mostly from film schools or

film cooperatives, while some even own their own equipment) and their greatly

improved image and audio recording quality, this had led to a matched

professional standard of much of their work.

The

Toronto DIY filmmakers can be seen as the spiritual successors to the Toronto

New Wave of the mid-eighties (and perhaps even further back to Don Owen making

one of the first Toronto films in 1964) as many of the ideas of an original and

challenging new Canadian cinema along with publicly debated issues and

problems, in terms of financing and distribution, have remained quite constant

since the eighties.* For example, Aaron Taylor in Great Canadian Film Directors writes,

Collectively,

the Toronto New Wave turned its back on traditionalist representations of urban

Canada, contributing to the formation of a recognizable national cinema that

finally made its presence known in the international market.

While

Paul Salmon, also in Great Canadian Film

Directors, characterizes the Toronto New Wave in more depth as,

Emerging

in the mid-1980s, this group shares a number of basic characteristics,

including: a rejection or at least deep questioning of the entrenched Canadian

tradition of documentary realism, an openness to experiment in terms of narrative

structures and subject matter, and a willingness to embrace collaboration and

artistic versatility. While many New Wave filmmakers have been outspoken in

their interest in remaining in Canada and in supporting an indigenous Canadian

film industry, they often share an equally fierce desire to remain unfettered

by any sense of obligation to focus on traditional Canadian subjects.

But

were the Toronto New Wave or even now the Toronto DIY Filmmakers truly

independent, and what does this even mean? Well the answer is complicated.

Though some of the filmmakers receive Canadian art council grants and others

investments from Telefilm, it is never guaranteed. Others crowd-source money

from friends and family and make their films with a small group of friends while

others actually have their own production company and are actually paid to make

films or shows. So there is a broad spectrum of economic resources available to

them, which varies depending on their commercial and critical success and where

they are in their careers.

But

perhaps, and to further connect the Toronto DIY filmmakers with the earlier

Toronto New Wave, it is actually Bruce McDonald, from his special Outlaw

Edition of Cinema Canada which he put

together in 1988, who offers one of the best portraits of what are the goals,

drives, and desires of what it is like being a young working independent

filmmaker (which necessitates also having another, ‘real’ job to afford living

costs) in Toronto,

This

issue is on the concerns and viewpoints relating to the Toronto independent

film community as opposed to the film

industry, the Outlaws as opposed to

the Establishment Cats. We’re sending this out as a communiqué from one

community to another with the hope of offering an alternative view of

filmmaking in this city… The Toronto Independent Filmmaker is a hard bird to

define because the work covers the spectrum… If there is any trend or school

emerging from Toronto the Good, it must have something to do with the desire to

break on through to the other side. It is definitely not a political cinema or

a cinema of urban realism. Many of the films are attempting to open portals

into surrealism and stepping through the stiches in time… Toronto filmmakers

are creating the Cinema of Escape. Not escapist

cinema by any means, for the work has the highest respect for its audience,

but a way out of our home turf as we know it, flying deeper into the century,

venturing into a world where time loses its meaning, searching for someplace

west of lunch, someplace close to the edge, somewhere where East meets West and

north and south do not exist. Living, growing, and working in a city as stolid

as Toronto, this is not a difficult concept to grasp… Now as far as the term outlaw goes, one might argue that these

people can’t be coined as true outlaws because they’re all camped out on the

doorsteps of every government funding agency in the book. Yet I would argue

that the term does apply ‘cause we’re just casing the joints, every damn one of

us is on the run from at least three people we owe money to, we operate outside

the established parameters of tried and tired formulas of film production and

storytelling and, most important, we realize and revel in the fact there are no rules. We’ve discovered that nobody

else really knows what’s going on, and we aren’t going to put all our precious

time into pretending like we do. We’re going to drive all the way till the

wheels fall off and burn. The term Independent

is quite useless, especially in this country where there is no studio

system to be independent from… The enemy of the would-be outlaw filmmaker lies

first in themselves, and in the timidity of the community and industry in

thinking there are rules they must follow. There ain’t.

David Davidson

***

Toronto DIY Filmmakers

Kazik Radwanski (1985 – )

Films:

Assault (2007), Princess Margaret Blvd. (2008), Nakuru

Song (2008), Out in That Deep Blue

Sea (2009), Green Crayons (2010),

Tower (2012), Cutaway (2014), How Heavy

This Hammer (2015).

Born and raised in

Toronto, east of the Don Valley River around Riverdale and the Danforth, having

attended the Montcrest school and then film production at the School of Image

Arts at Ryerson University, Kazik Radwanski has the privilege of making the

first full length feature of the Toronto DIY movement Tower (2012), about an odd young man Derek who pursues an animation

passion project while also working construction for his uncle and trying to

find a girlfriend. The Toronto DIY filmmaker movement came to fruition with Tower as the film was full of subtle and

important Toronto references from its focus on young adult anxieties, engaging

with a less seen and personal encounter with the city, to its title that refers

to the iconic CN Tower, to prominently featuring one of the city’s more

infamous habitants, that of the ubiquitous raccoon. Tower also benefited from receiving critical acclaim and

international attention as it had its international premiere at the 2012

Locarno Film Festival before playing in the city at TIFF.

Tower is important because it provided the start of the

rise of the movement’s young and unique perspectives on the Toronto experience.

Radwanski speaks about making the film in a Toronto DIY Filmmakers feature on

The Slate,

When

I made Tower and my first few shorts

it really felt like I was all alone. I looked up to people like Denis Côté and

Nicolás Pereda but there was no one making English-language films that I really

related too… I like to tell stories that I feel are true to Toronto. I’m not

sure exactly what they are but I know what they are not. I don’t want to force

big stories on the city.

Tower was the logical conclusion of Radwanski’s MDF

trilogy (which gathered its name from his and his producer Dan Montgomery’s

production company Medium Density Fibreboard Films) that includes the three

short films Assault (2007), Princess Margaret Blvd. (2008) and Out In That Deep Blue Sea (2009), which

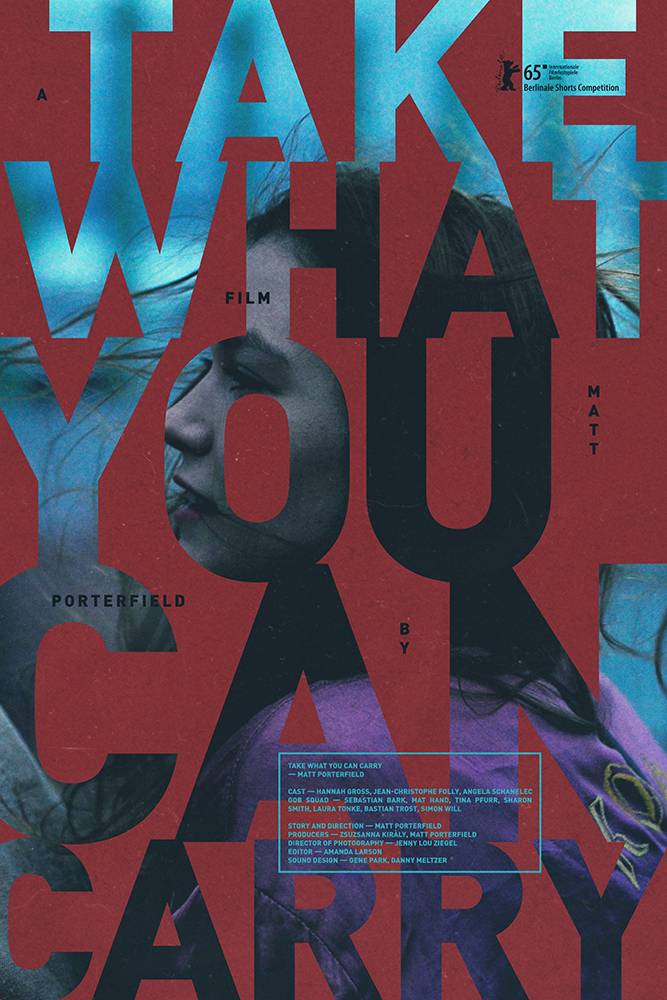

all gathered attention from premiering at the Berlinale Shorts Competition.

Radwanski speaks about the transition in an interview with Adam Nayman in Metro Toronto as, “I’d spent so much

time developing characters (in my shorts) that it seemed like a shame not to do

more. We wanted to allow ourselves more time to dig deeper and live with the

characters longer.”

Since

then he has made Cutaway (2014) a

sorrowful study of the death of child through expressive Bressonian close-ups

of hands, which he dedicated to his father who had recently passed away. His

sophomore feature How Heavy This Hammer

(2015) continues the project of Tower by

focusing on another odd Torontonian, a father of two sons, as he avoids taking

care of his health, has conflicts with his wife that leads to a separation,

violently playing rugby and sitting at his computer playing a Viking-oriented

computer game. Radwanski and Montgomery are also responsible for the exciting

MDFF Screening Series, now at The Royal, which is the unofficial social hub for

many of the Toronto DIY filmmakers. He is also now in the process of getting

his Masters in film production from York University where he has a few

different projects in the works.

Matt Johnson (

– )

Films: Nirvana: The Band (2010), The

Dirties (2013), Operation Avalanche (2016)

In an interview with The Seventh Art in 2013 Matt Johnson

spoke about how that there was not a young Toronto filmmaker community, and

perhaps he was right, but since then in the following few years many of these

filmmakers came to know each other, meeting in Toronto or abroad at film

festivals through mutual acquaintances, film critics and programmers, and since

then more of their films have been screening publicly in the city while more

filmmakers have also been appearing, graduating from film schools or moving to

Toronto from other cities. Johnson has been one of the most public and

encouraging figures of the first generation Toronto DIY filmmakers through

providing crash courses in DIY filmmaking in one of the Nirvana: The Band audio commentaries and publicly advocating for

more support networks for younger filmmakers. By actively making films in

opposition to more traditional funding bodies (whose mandate and criteria has

the potential for a homogenizing effect) Johnson’s films are refreshingly

original in terms of Canadian cinema as they address particular taboo subjects:

a dark comedy high school shooting film (The

Dirties) and a Stanley Kubrick moon landing conspiracy film (Operation Avalanche). By skirting the line between

documentary and fiction (most of his work is labeled as being ‘documentaries’),

which coincided with a loosening of fair use laws, Johnson has been able to get away

with appropriating more commercial images than most others (who would have to pay large fees to include them). The web-series Nirvana:

The Band was about two young musicians, Johnson and Jay McCarrol (playing

versions of themselves), trying to book a concert at The Rivoli. This critique

of privileged cultural institutions is pursued further in Operation Avalanche (2016) against the CIA and will take on an even

more national dimension in Johnson’s proposed critical John A. Macdonald

biopic. Johnson, unique in this movement as an actor-filmmaker, has taken to

acting in the films of some of the Toronto DIY filmmakers, such as Pavan Moondi

and Brian Robertson’s Diamond Tongues (2015),

Radwanski’s How Heavy This Hammer, and

Calvin Thomas, Yonah and Lev Lewis’ Spice

it Up. (And some of them have

even returned the favor by having small roles in Johnson’s films). Johnson’s

production company Zapruder Films is best seen as a collaborative community,

all taking on other projects to stay active, but returning to Johnson’s films

for their originality and audacity.

* They include the

producer Matthew Miller, who previously directed Portage (2008), the co-writer Josh Boles, the assistant director

Matt Greyson, the cinematographer Jareed Raab, who is credited for the

Johnson-written The Revenge Plot (2011),

and the former co-writer Evan Morgan who has a new feature in the works.

Pavan Moondi, Brian Robertson ( – )

Films: Everyday is like Sunday (2013), Diamond

Tongues (2015), Sundowners (in

production).

After founding the online

video interview film magazine The Seventh

Art along with Christopher Heron, Pavan Moondi and Brian Robertson took to

filmmaking (with at first Robertson just producing, before they would start to

co-direct). So far they have been the best at representing Toronto as a young

party city (which is paralleled by some of their own production stories and

launch parties), even though it is still presented as a city leveled with a

frustration of unfulfilled ambition, difficulty of finding work and romantic

separation. With an attempt to maintain a true geography of the city,

recognizable locations such as the Dundas and Ossington blocks, the Queen

street strip of malls and other smaller neighborhoods are regularly in the

background or are used as exposition to be as faithful to the representation of

the city as it is lived through personal experiences. Through its specificity

the films allow for a stronger identification with its story. Everyday is like Sunday (2013) is

interesting, though flawed, due to a rushed and partly unprepared

pre-production. Inspired by the teenage melodramas of American television, such

as The OC (2003-2007), and also a

Morrissey song from where it gets its title, Everyday is like Sunday is about a few friends dealing with love

issues, friendship and trying to find work in Toronto. Moondi and Robertson’s

follow-up Diamond Tongues (2015)

about a struggling actress is more varnished and successful as it was made with

more pre-production and on a larger scale, with a better lead actress (Leah

Goldstein, from the band July Talk) and more financial resources. Diamond Tongues was generally well

received, which has led to bigger projects for the duo that includes Sundowners which will be set in Mexico

and will star the stand-up comedian Phil Hanley, Luke Lalonde from the band

Born Ruffians, and Tim Heidecker from Tim

and Eric.

Andrew Cividino (

– )

Films: I

Norbert (2007), Mud (2009), We Ate the Children Last (2011), Yellow Fish (2012), Anatomy of a Virus: The Making of Antiviral (2013), Sleeping Giant (2014), Sleeping Giant (2015).

The unexpected success of

Cividino’s career so far has been the selection of his first full-length

feature Sleeping Giant at the 2015

Cannes Critics' Week (a first for any of these filmmakers), which gathered it a

plethora of accolades, who were happy to see a good English Canadian film by a

young Toronto filmmaker finally playing at the prestigious and hard-to-get-into

French festival. The story is about three young boys spending their restless

summer in Thunder Bay. Cividino allowed the boys to just be themselves and to

improvise, which led to some really great and surprising moments in the film.

For his follow up Cividino will turning his earlier short-film We Ate the Children Last, based on a

Yann Martel story, into a feature. Cividino works closely with his producer

Karen Harnisch (who also produced The

Oxbow Cure and has an upcoming collaborative project in the works, Delta Venus) as they run their company

Film Forge Productions together. Cividino’s short films Mud and We Ate the Children

Last were both co-directed with Geoffrey Smart and he also made the

making-of Brandon Cronenberg’s Antiviral (2012).

Calvin Thomas, Yonah and Lev Lewis ( – )

Films:

Amy George (2011), The Oxbow Cure (2013), Spice It Up (2015), Sublet (production).

The feature film Amy George (2011) brought the working

pair of Calvin Thomas and Yonah Lewis to the forefront of young Toronto DIY

filmmaker movement. It is a film set in the Riverdale neighborhood where a

young teenager Jesse has trouble fulfilling an assignment of taking a

photograph that best represents himself. His teacher's advice is “you can find

something interesting anywhere… you just have to look around,” which gets Jesse

to explore his neighborhood and nearby parks to find something that meets this

description. Experiencing anxiety about not being able to be a true artist

without having experienced ‘true suffering’ (something which he read in the

library in a book on the subject of being an artist) Jesse becomes worried that

he might not be able to complete the project. With troubled relations with his

parents, since they do not trust him and think that he is odd, Jesse ends up

being closer with his younger aunt who he talks to bout his romantic affinity

for a classmate Amy, who after playing with would become a source of guilt.

Thomas and Lewis’ sophomore film The

Oxbow Cure (2013) is darker and more brooding as in it a young Toronto

woman retreats to a Muskoka cottage to recover from an illness and the death of

her father (perhaps as an answer to the notion of the necessity of suffering

for serious artists as mentioned in Amy

George?) and once there is haunted by fantastical visions. The Oxbow Cure is a singular film for

the Toronto DIY filmmaker movement as it is combines elements from an Ingmar

Bergman drama (The Passion of Anna is

said to have been an influence), experimental cinematography of nature à la Philippe

Grandrieux (Un lac) and a vintage style

hand-crafted movie monster (Swamp Thing).

Thomas and Lewis are perhaps the Soderberghs of the Toronto DIY filmmakers as

they work quickly and economically with a close team and Thomas and Lewis

operate their own cameras. Yonah Lewis’s brother Lev started working with them

as the composer of Amy George before

taking on more responsibility to the point of co-directing their latest feature

Spice It Up (which still has not

premiered) to now directing his own feature Sublet.

Fantavious Fritz (

– )

Films:

Kosmos (2011), Tuesday (2012), Paradise

Falls (2013), Lewis (2015).

A well-regarded

short-filmmaker, having his work play at Short Cuts Canada at TIFF and even

some getting on Canada’s Top Ten, but it was the audacity and warmth of Lewis (2015), which premiered at the

MDFF screening series, that brought Fritz a lot more local and critical

attention. Lewis is a story told from

a cat’s point of view as he gets lost from his owner and starts to be taken

care of by a senior woman. Lewis (the cat’s name) still gets to wander around

the neighborhood, seeing the sights and having fun with kids, but he returns to

her every night, where she discusses with him the sadness’s of her life and

lovingly dances with him. Unfortunately she passes away one night and Lewis is

trapped in the house, with very few ways to get out… Fritz moved to Toronto in

2011, and since then has formed a working team, who they share projects with,

such as making music videos, while also having day job working on commercial

media. In one of his earliest projects which he co-created with Austin Will, the bartender slides me a beer it runs down

the bar like an Olympic sprinter, (2011), which title comes from a Charles

Bukowski poem and whose voice-over is Bukowski reading a different poem Style, it is defined as “A fresh way to

approach a dull or a dangerous thing… To do a dangerous thing with style is

what I call art,” and, “Cats have it with abundance.” Stylish and cat-like, a

great way to characterize the beautiful work of Fantavious Fritz.

Nadia Litz (

– )

Films: How to Rid Your Lover of a Negative

Emotion Caused by You! (2010), The Frame with Adrienne Clarkson (2012),

The Good Escape (2013), Hotel Congress (2014), The People Garden (2016).

A popular Canadian

actress before becoming a filmmaker, Nadia Litz perhaps offers one of the best

models of how to remedy the gender disparity in feature filmmaking: for young

women to just go out and make films themselves. Litz’s first feature Hotel Congress (2014), which she

co-directed with Michel Kandinsky, was made as part of the Toronto independent

filmmaking veteran Ingrid Verninger's 1K Wave, which recruited a myriad of

younger Toronto filmmakers to make a film for under one-thousand dollars. This

DIY catalyst makes Hotel Congress even

more impressive as it was filmed at the real Hotel Congress (where the film

gets its title) in Tucson, Arizona. Hotel

Congress is a reflective, witty and funny comedy about a man and a woman

who are at the hotel to have an affair in which they promise to be

non-committal but where they inevitably fall in love. Perhaps a generation

older than the DIY filmmakers the ethos of Hotel

Congress definitively gives Litz a place within this movement. As well,

along with others like Simon Ennis (You

Might as Well Live, Lunarcy!), Daniel Cockburn (You Are Here), and Reginald Harkema (Monkey Warfare, Manson, My Name Is Evil), this generation of

filmmakers fills the transitional years between the Toronto New Wave and the

Toronto DIY filmmakers, through how they were able to express their youthful

new directorial voices through more industrially driven projects. Litz new

feature The People Garden (2016) is

screening theatrically in the summer of 2016 and includes an impressive cast, such

as Dree Hemingway and Pamela Anderson.

Rebeccah Love (1990– )

Films: Pitching for the Heights, (2013), Circles

(2013, as the writer/art-director), Abacus,

My Love (2014), Drawing Duncan Palmer

(2016), Props Girl (2016), Acres (in production).

Has there even been a

Toronto filmmaker as committed to showcasing the beauty of Regal Heights before

Rebeccah Love? Probably not, as since Love’s first short-film Pitching for the Heights (2013) about

two friends exploring the neighborhood, playing baseball, and nostalgically

recalling their youth; the neighborhood, its charm and slower pace has never

been as beautifully portrayed. Love’s films are a nice counter-point to some of

the more male-centric downtown work of a lot of the Toronto DIY films. A

feminine and intimate filmmaker, Love’s Abacus,

My Love (2014), her Ryerson graduating project, is a fairy tale of a young woman who finds the man of her dreams

to rescue her from a despairing life. It is impressive for its theatrical

effects and lavish production design. In a cinema filled with mourning and

sorrow (the boy and father missing their mother in Circles and the missing mother in Abacus), the belief in dreaming and for something magical proposes

the remedy to so much of life’s despair.

Drawing Duncan Palmer (2016)

still needs to have its premiere and Love has a new project Acres in the works.

Sofia Bohdanowicz ( – )

Films:

falling with force. (2009), Dundas Street (2012), A Prayer (2013), An Evening (2013), Another

Prayer (2013), Last Poem (2013), Never Eat Alone (2016), A Drownful Brilliance of Wings (2016), Maison du bonheur (2016).

Since the Consulate

General of the Republic of Poland gathered five of Sofia Bohdanowicz short

poetic films for a small retrospective Last

Poems in 2014 there has not been any more public screenings of her work,

even though since then she has made three more of them. Bohdanowicz’s greatest

claim to fame in the Toronto DIY filmmaker movement is her short film Dundas Street (2012), named after the

famous street that stretches across the city, which is inspired by one of

Bohdanowicz's grandmother Zofia Bohdanowiczowa’s (1895-1965) poems. Dundas Street is less a narrative than a

visual poem, which emphasizes striking scenes and visual beauty. Dundas Street, which is co-directed by

Joanna Durkalec, is set in the past (when Zofia would have first moved to

Toronto) and is narrated by an elderly Polish woman who is discusses being

unable to adapt to her new urban landscape. Dundas

Street follows her efforts to find meaning in an inhospitable and

unfriendly city. She speaks fondly of the fruit merchant Cornelius and in one

stunning scene as he is cashing out, the lighting brightens, and he sings a

sorrowful song. Hopefully more of Bohdanowicz’s newer work finally plays

publicly on Toronto screens.

***

First Generation Toronto DIY Filmmakers

Nicolás Pereda (1982 – )

Films:

Where Are Their Stories (2007), Interview with the Earth (2008), Juntos (2009), Perpetuum Mobile (2009), All

Things Were Now Overtaken by Silence (2010), Summer of Goliath (2010), Greatest

Hits (2012), Killing Strangers

(2013), The Palace (2013), The Absent (2014), Minotaur (2015), Tales of Two

Who Dreamt (2016, which he made with his partner Andrea Bussmann).

Igor Drljača (1983 – )

Films: The Battery-Powered Duckling (2006), Mobile

Dreams (2008), On a Lonely Drive

(2009), Woman in Purple (10), The Fuse: Or How I Burned Simon Bolivar

(2011), Krivina (2012), The Waiting Room (2015).

Albert Shin (

– )

Films:

Pin Doctor (2006), Kai’s Place (2008), Point Traverse (2010), In Her

Place (2014).

Luo Li (

– )

Films:

Fly (2004), Ornithology (2005), stills (__), I Went to the Zoo the Other Day (2009), Rivers and my Father (2010), Emperor Visits the Hell (2012), Li

Wen at East Lake (2015).

The First Generation

label is a sub-group of the Toronto DIY filmmakers that categorizes filmmakers

who immigrated to Toronto, Canada earlier on in their lives and studied, for

the most of them at the film production program at York University, and with

the skills, resources and community which they formed, took to filmmaking, with

some making Toronto or Toronto-related, films, back to their country of origins

to tell prescient stories affecting their own home country, while still

returning to Toronto afterwards, where many of them live the rest of the year.

The

term was coined by Radwanski who in 2011 programmed a First Generation series

at the Lichter Filmtage in Frankfurt. Radwanski describes the initiative,

We

were given carte blanche and told that we could program anything we like as

long as it related to Toronto. Frankfurt is Toronto’s sister city and one of

the festivals missions is to celebrate that fact. However, we soon found that

all of our favourite local filmmakers were from somewhere else.

The

focus of the program was on how the filmmakers could be informed by their city

and its inhabitants, while also removing this context from their films.

Radwanski define them as, “These temporary-residents play a role in Canadian

cinema: their films maintain a connection to Toronto, while defining their own

territories and landscapes.” Since this program in 2011 these First Generation

filmmakers, and others which includes also Second and Third Generation

immigrant filmmakers, have only rose in prominence. There is an emphasis on

international co-productions and funding for this group. For example, Nicolás

Pereda works closely with the Mexican production company Interior XIII and Igor

Drljača has received the Hubert Bals Fund for project development on a new film

Tabija. As well, these films have

easier access and international recognition to play at more and different

international film festivals and cities, whose mandate is to play more films

from those other respective countries.

From

this group Nicolás Pereda is perhaps the most prominent. Pereda moved to

Toronto from Mexico at the age of nineteen to enroll in film production at York

University. With his first feature film Where

Are Their Stories? dating from 2007, in interim he has created a dozen

films, ranging from full-length features to medium- and short-films, to pure

fiction films to hybrids and documentaries. Pereda’s films are typically set in

and around Mexico City, with a cast including his regular repertoire actors

Teresa Sánchez and Gabino Rodríguez (whom typically play mother and son), dealing

with themes of alienation and class disparity, and are characterized by motifs

of repetition and formal experimentation.

Pereda’s

low-budget minimalist form of filmmaking is also open to experiment with

narrative and structural patterns. The splitting of the films into two parallel

and contrasting parts regularly appears (perhaps an influence of Apichatpong

Weerasethakul?) to interrogate and dissolve certain ideas of representation. As

he discusses with Radwanski in a Cinema

Scope interview, “Maybe you watched the Dardenne brothers and I watched

Tsai Ming-liang or something like that…” These kind of hyper-conscious forms of

storytelling might at first glance appear to be jarring, but they allow Pereda

to interrogate his own motives and the filmmaking process. The films are

character driven, with minimal plots, with typical scenes involving characters

siting together in a slum-like room for long durations without any dialogue,

filmed in a fixed long take. Typically there are also retreats to nature, which

is never as utopian as the characters would desire.

Since the 2012 TIFF Cinematheque retrospective Where Are the Films of Nicolás Pereda?

(as the title seems to anticipate) Pereda’s recent films have not screened

publicly in Toronto, except for Minotaur in

the 2015 TIFF Wavelengths program. But this is not to suggest that Pereda has

not been busy as since then he has made Killing

Strangers (2013) with the Danish filmmaker Jacob Schulsinger as part of

Copenhagen’s DOX:LAB collaborative initiative; his own films The Palace (2013), The Absent (2014) and Minotaur;

contributed to Venice 70: Future Reloaded

(2013) and Gael Garcia Bernal’s omnibus film El aula vacía (2015); and finally made his first Toronto film, Tales of Two Who Dreamt, a documentary

with his partner Andrea Bussmann, about the Hungarian Laska family in a

low-cost housing complex as they await their day in court to confirm their

asylum in Canada. As well Pereda has returned, now as a professor, to York

University to teach a new generation of students film production.

Drljača and Albert Shin have had a close working

relationship since their time at York. Drljača was born in Bosnia and

Herzegovina and moved to Canada with his family due to the Bosnian War (the

subject of his autobiographical The Fuse).

Shin, a Second Generation immigrant, was born and raised in Ottawa, and went to

York for film production and has been living in Toronto since. They work

together at their production company Timelapse Pictures, balancing directing

and producing roles on each other’s films. Drljača’s two feature films Krivina (2012) and The Waiting Room (2015) are both partly set in Toronto (more so The Waiting Room) even though they both

primarily deal with the Sarajevo diaspora (in Krivina the protagonist returns there), which is also the subject

of many of Drljača’s short films. Krivina

stars Goran Slavkovic (who Drljača has worked with on his earlier short

films) who brings to the humble wanderer Miro a tough outer-shell with a buried

sensitivity. The story is about Miro, a Bosnian refugee who works in

construction, who returns to Bosnia and Herzegovina to search for an old lost

friend who has been rumored to have reappeared. His other friend Drago (played

by the Bosnian actor Jasmin Geljo) has many conversations with Miro as their

driving to work in which he complains about the Harper government’s immigration

policies.

Geljo would return as the lead in The Waiting Room (and so would Slavkovic in a bit role) as a

stereotyped working actor. He was prior a famous actor in Bosnia and now he is

making a film in Toronto on a production stage about the wartime experience (the

opening scene with its rear-projection is stunning). Geljo’s character has

fraught relations with his whole immediate family: estranged from his first

wife who is now in a terminal cancer ward, he is in what appears to be an

unfulfilled second marriage, gets in fights with his daughter and cannot always

relate to his son. The Bosnian psychic landscape that Geljo’s character left

over twenty-years ago is omnipresent throughout the film. He tends of find

solace in the intimate conversations in his own language with his closer friends,

re-interpreting his native comedic performances, over drinks, as a last bastion

of his previous life, which he can’t really express with anyone else. And even

these moments end up in anxiety, frustration and misery. There are some wounds

that cannot be healed – the psychic memory of the Bosnian war has left more

victims than just the casualties.

Formally the major influence on Drljača is Andrei

Tarkovsky from the oneiric narrative structure and temporal leaps, reality and

dreams seamlessly blending together to create something extremely hypnotizing.

Two particular big influences are The

Mirror (1975), for its flashback narrative structure and how it engages

with the fracturing psychological effects of wartime experiences, and also Solaris (1972) for its famous

highway-driving scene that leads into the city (Drljača’s films are almost all

prominently set in or around cars).

While Shin’s better well known for his feature In Her Place (2014) which is a critique

of South Korean affluence as it is about a rich woman from Seoul who goes to

the countryside to secretly, and exploitatively, adopt an unborn child. Filmed

in South Korea, with a technical crew from both countries, Shin’s filmmaking

approach blends Lee Chang-dong’s poetic realism with Luis Buñuel’s sarcastic

surrealism. The difficulty to access Shin’s earlier feature Point Traverse (2010) and his previous

short films Pin Doctor (2006) and Kai’s Place (2008) makes him a subject

for further research.

And

finally Luo Li, with four completed features in the span of six years, he is

one of the more proactive filmmakers in the group. On top of that they have all

had public and repeated screenings in Toronto. His graduate student film I Went to the Zoo the Other Day (2009)

onwards to Rivers and my Father (2010)

and Li Wen at East Lake (2015) all

played at the Images Festival, while Emperor

Visits the Hell (2012) played at the MDFF screening series, before they

would all return for a TIFF Cinematheque retrospective, You Can't Go Home Again: The Films of Luo Li, in the summer of

2015.

Born

in Wuhan, China, Li moved to Toronto to receive a BFA and MFA from York, and

now lives in Hamilton, while returning to China to make his feature films.

Perhaps his only true Toronto film is his first I went to the zoo the other day where two young Yugoslavian

immigrants go to the city’s zoo, to overcome their depression and to experience

the animal life. Made without any form of official permission, in an artistic

black-and-white cinematography, with dialogue in Serbian, dealing with themes

of alienation, an inability to communicate and personal reservations; it is one

of the more stunning Toronto films from this group. Li’s following films are

experimental documentaries set in China, that attempt to bridge the personal

with the political, as he interrogates his own motives for going there and

working while also examining the negative effects of the country’s rapid

capitalism. For their meditative tone, use of fantasy, raw social portraits,

and heightened and regular casting of the same actors they recall the films of

Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Tsai Ming-liang.