-

Raging

Bull (1980). La Solitude Sans Fond, by Pascal

Bonitzer. Cahiers du Cinéma N.321. March 1981. Pg. 5-8. *Cover

-

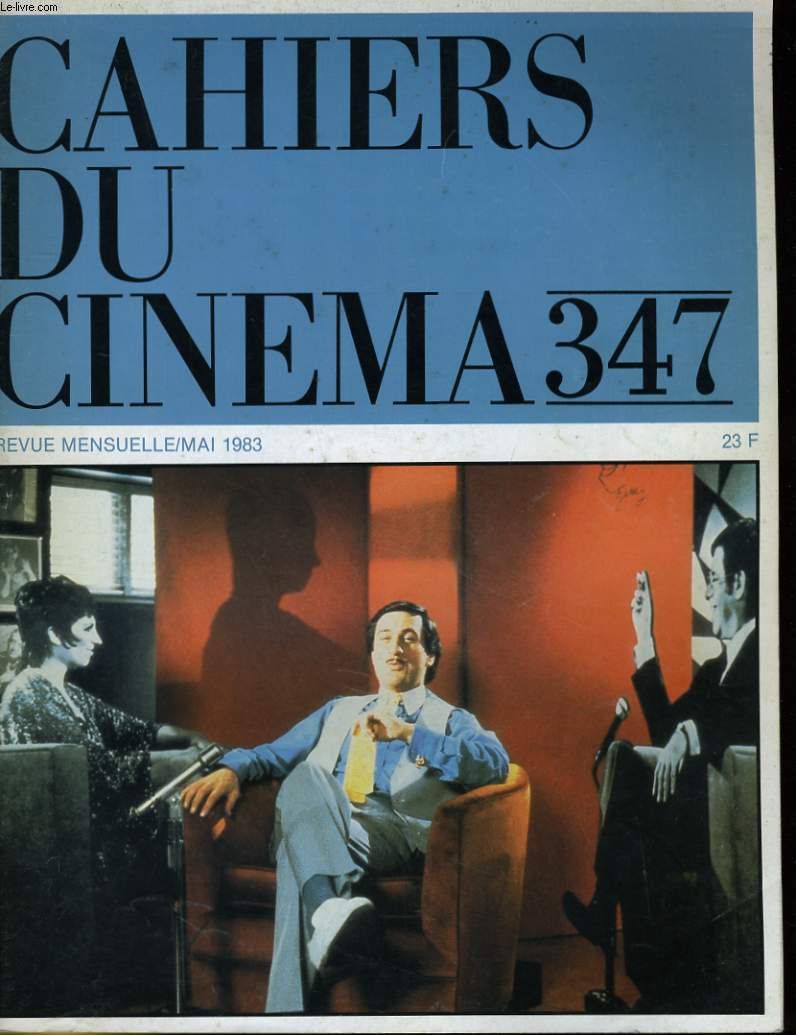

The

King of Comedy (1982). De l’Autre Coté des Images, by

Olivier Assayas. Cahiers du Cinéma N.347. May 1983. Pg. 5-8. *Cover

-

After

Hours (1985). Mâchoires, by Pascal Bonitzer. Cahiers

du Cinéma N.383-84. May 1986. Pg. 43-44.

-

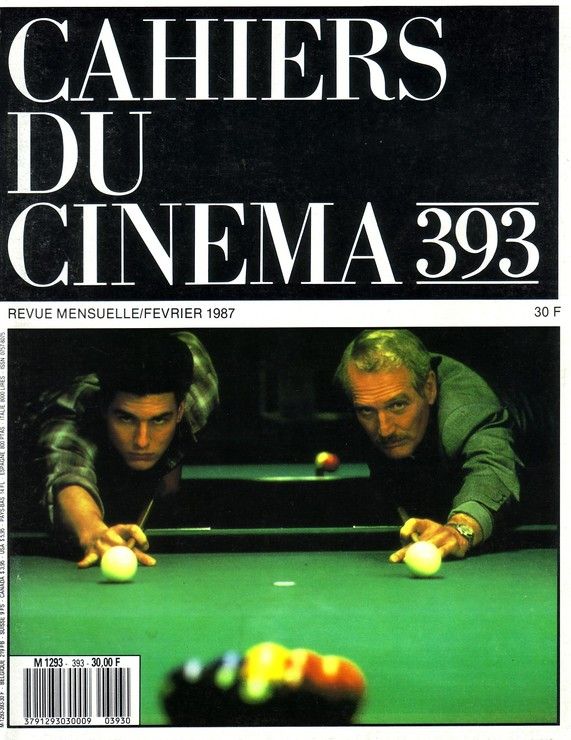

The

Color of Money (1986). Le Maître du Jeu, by Alain

Philippon. Cahiers du Cinéma N.393. March 1987. Pg. 5-7. *Cover

-

The

Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Portrait de Jesus en Héros Scorsesien,

by Antoine de Baecque. Cahiers du Cinéma N.412. October 1988. Pg. 5-8. *Cover

***

Raging Bull would be the introduction of Martin

Scorsese at Cahiers after their

political-theoretical period. Prior to this first Critique by Pascal Bonitzer

(one of Daney’s critics), Scorsese might have been mentioned only in passing.

Scorsese was part of this new generation of American directors, along with Coppola, De Palma, Spielberg, and Allen that Cahiers was discovering and catching up

with. Raging Bull offered them their first opportunity

to write a Critique on the director and it

would be the start of their relationship with the American director who they

would give the most covers (4) throughout the Eighties. Along with the review

there’s an interview with its producer Irwin Winkler and its editor Thelma

Schoonmaker in the Journal section to correspond with the Critique.

Bonitzer’s

review proceeds in three subtitles:

The Aesthete, The Priest,

and The Thug

“The

life of Jake LaMotta, based on his own autobiography. We could have expected a

sort of retro-fresco, with one side The

Godfather and the other side Fat

City, grandeur and misery, lost illusions, sports and the mafia, a social

truthfulness and an auto-critique of American society etc. The film which is in

black-and-white (except for a few brief exceptions), we could have thought that

it would resemble Bob Fosse’s Lenny,

an evocation of the Fifties and the portrait of an artist as struggling and

neurotic. This isn’t the film at all.

“Martin Scorsese is an artist with a

Dostoevskian sensibility, and not Balzacian. A description of social or

historical facts doesn’t interest him as much as the life of the human spirit.

There is three personalities in this filmmaker: a priest, a suicidal thug, and

an aesthete (which were already all there in his first experimental 16mm film, The Big Shave). The priest is behind

the camera, the thug is in front, and the aesthete is in between. Each of his

(their) films is its own rendition, the deployment of this trinity.*

As it happens

there is a women who witnesses this, who becomes the object or the cartelist

for this tri-partition, but this always leads to (or well, most of the time)

these films where one or two characters are analyzed very closely. This brings us

to Raging Bull.

“Boxing has the same metaphoric and

metaphysical role as the taxi: it expresses identically this solitude, the

tragic identity of this character which the character can’t escape. The boxer

boxes against his shadow, against walls (c.f. the prison sequence). Sugar Ray

Robinson isn’t a black opponent, but his shadow.

“Broadly speaking, Raging Bull is a study in a wide-shot

of the implications of love, sexual desire and jealousy. La Motta is an avatar

of Othello in the era of competition.

“Raging Bull is then maybe also a beautiful love story. Vickie,

or/and Cathy Moriarty, are who inspire Scorsese. She is what’s carnal, the

medium of a passion of cinema, which edges towards a fetishism of the filmic

material. Scorsese is (with Godard) one of the rare directors to possess this

sensual taste for filmic material, which overflows into an abstraction, and

that leads to his experimentation with this black-and white and Super 8 film

stock. This pseudo-amateurish footage troubles the film, and through these

moments of family happiness, breaks the heterogeneous fabric of the film, like

in a painting by Rauschenberg or an atonal composition.

“By the end, and regardless of the

punctuation of its evangelical finale, the Catholic God and this creature resolves

their problems through lighting, in a pure affirmation of cinema, like how in Mean Streets, Harvey Keitel’s puerile

hell concluded in a fascinating explosion of flames.

* This trinity shouldn’t be confounded with the triangle Scorsese-De Niro-Schrader (where Schrader played the role of the priest and De Niro the thug). It is necessary to watch that De Niro and Schrader do elsewhere to understand that they constitute here moments, in the dynamic sense, of Scorsese. And why they’re so good makes Scorsese the auteur. (It’s curious how this notion of an auteur in the cinema is still polemic today). The solitude of the white male protagonist: this is what connects Raging Bull to Taxi Driver, they are both variations on a similar character.

***

With The King of Comedy comes another Scorsese

dossier, which includes a Critique by Assayas, an interview with Scorsese by

Barbara Frank and Bill Krohn (who also has another essay). It’s a generally

impressive issue: Serge Daney reviews Jerry Lewis’s Smorgasbord, Serge Toubiana reviews Robert Bresson’s L’Argent, and there’s an homage to André

Bazin (for the publication of the Dudley Andrew biography in French).

Oliver Assayas (again,

also a Daney critic) in his review of The

King of Comedy illustrates a few qualities of what makes a Cahiers Critique unique: their extreme

movie love, a prose that borders onto the purely interpretive and nonsensical,

a refined understanding of the film and its relationship to the director’s body

of work, the work of the director’s collaborators and what they bring to the

project, a large knowledge of film history, and how the film documents certain

social trends in American culture. Assayas’ review also references the Cahiers Made in U.S.A. issue (which

Assayas participated in the making) where they published a conversation between

Scorsese and Schrader.

“There

isn’t a satire nor a parody and its scrupulous realism is what makes it so

powerful. In his recent films, Scorsese has strictly stuck to genres and the

formal rules of Classical Hollywood. On a subject like this one, we would have

expected to see an approach inspired by Capra. But it’s exactly the opposite! The King Of Comedy doesn’t resemble

anything by the fact that it is a film by a cinephile: it’s a contemporary

film. It’s a new kind of film, and

this is rare.

“The

America of The King of Comedy is in

effect an acclimatized nightmare, a

superstore that has the dimensions of a nation, a system with the essence of

socialism or of a uniformity of individuals, like those of ideas, they are no

longer created. The process has been completed.

“The way that Scorsese and De Niro

make the films they choose to make, which are relatively commercially

unsuccessful, have led them to realize something clearly: that the American society had been solidly

armed to reject this supplement of the spirit that they were proposing. Just as

much with Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, New York, New York and Raging

Bull. These are films impregnated with a belief, full with a moral and a

spirit, and with the mission of the artist to defend these spiritual values in

face of uncaring contemporary society. This is why a film like The King of Comedy is just as much an

artistic film as it is a film noir,

destructive and somber in its discouragement.

“The film is unacceptable for being

so profoundly subversive. It touches upon, in effect, really closely what today

it means to create an image. This is America. This is Hollywood. This is the

system and these are the individuals that it creates. This is how they reproduce.

“There isn’t any content, there’s

only this form. Regardless of what’s the nature of what we do, the only thing

that counts is the energy that we put into it. A figure like Jerry Langford

holds on to his scar regarding this, in his silences resides something of his

spirit, he’s a being who’s suffering. While Rupert Pupkin is, himself, already

ready to assume everything: from the other side, the spectacle is not his

mirror, he’s the mirror of the television. He only sends back to Jerry Langford

his own image. Rupert Pupkin is the horror of the man without a spirit; he’s

the pure emanation of the man who succumbed to the media. He was born into a

generation where everything is the same thing as its image, and through this

his substance is the same thing as his essence: he isn’t more than what we see,

but he’s the incarnation of his

appearance.

“Rupert Pupkin dreams of passing

through the image: that’s where he belongs. And, just like in E.T., he wants to go back home. But in

reality there isn’t anything on the other side. And this nothingness, which is

carpeted in red, is literally hell. And for this The King of Comedy, without a doubt Scorsese’s most audacious work,

is a horror film. Founded on a nightmare logic, it reminds the viewer of an

adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial that

Welles directed. This makes us regret the fate of K.: at least he had a future.

***

After Hours would be the only Scorsese film to not

get a cover in this period. It’s part of their Cannes Événement, France-USA.

Bonitzer returns to write his second Scorsese Critique. It’s a lengthy and serious

review of one of the director’s lighter films. It shows Cahiers’ loyalty and dedication towards Scorsese. The issue also

includes an essay by Michel Chion, Forma

Dolorosa, on a Scorsese retrospective at the Festival de Strasbourg (“Martin

Scorsese is one of the best working directors, one of the most important artists.”) and there’s an interview with

Scorsese, Into the Night, by Bill

Krohn.

“After The King of Comedy, Martin Scorsese

found himself alone and rejected. After

Hours brings him back into the circuit: it was a requested project, like we

know, by its principal comedian, Griffin Dunne, the co-producer on the film… After Hours, in its nightmare style, is

a light film, which doesn’t have the troubling qualities of Scorsese’s other

films, the deep anguish that weighted down his other films. The King of Comedy was a film that was profoundly

horrible. After Hours is only that

superficially… Anguish and fright, which are at the heart of the story, are

especially treated with a virtuoso direction. It is this virtuoso

demonstration, this grand style in itself, in this small subject, which is what

After Hours is putting forward.

“There is always an ecce homo in Scorsese’s cinema. So few

directors know how to transmit this deictic power, this value of an index of

one’s destiny, to the camera… After

Hours is a comedy of panic, just how like Topor and Arrabal defined it.

Despite its allusions to Kafka (its characters and the punk bar, for example), it

is actually more like Polanski’s The

Tenant in its use of the fantastic.

“After Hours is in reality, lastly, a satire on misogyny, which is

literally anarchic, where it’s through the character of Paul that it incarnates

its terrorizing expression.

“It’s the art of Scorsese to work on

two different levels, to take and squeeze us, existentially, in what is just a

diversion that is pretty dark. It’s a diversion, to repeat, but in a grand

style: what’s there to complain about?

***

Even The Color of Money gets a cover! This a

film that even one of Scorsese’s biggest American defenders Roger Ebert

publicly disapproved of. In the issue Scorsese is highlighted along with Clint

Eastwood’s Heartbreak Ride (a

director that was also taken more seriously earlier on in France).

In Alain

Philippon’s Critique (again, not necessarily a Toubiana critic) he describes

how in the Eighties Hollywood auteurs were experiencing an identity crisis, which forced them to make sequels and to take on more ‘commercial’ projects (e.g. Spielberg’s

episode of Amazing Stories). This led them to experiment with these new forms. It was Paul Newman that asked Scorsese

to make this sequel to Robert Rossen’s The

Hustler (1961).

“More and more the standards of the

American production system are tending to regress. It’s making more ‘series’,

remakes or even sequels (like how we

would describe a sickness). Their alternative American cinema is being quickly

reduced. It’s up to their few great directors to affirm their personality and

grandeur.

“The situation isn’t being played

exactly as a simple rupture, say on one side the ‘standard cinema’ against that

of the ‘auteur cinema’. To prove this: in The

Color of Money, Scorsese remains totally loyal to his own line and it’s

actually one of his richest films, even though it could have looked like a

triple handicap: a sequel, a major production, and an order.

“This

is the spiritual crisis that we get to see in The Color of Money. It’s another work that follows Martin

Scorsese’s questioning of ambition and self-destruction (Raging Bull), success and the trauma towards depressives (The King Of Comedy), and the desire for

a purification (Taxi Driver). In

short: the way that for a while now Scorsese has been able to examine the value

of the American society through its most recent incarnations. A fall, crisis, a

new start, and a comeback: this is the itinerary of Eddie, which is almost like

a religious conversion.

“Here Scorsese itinerary crosses

that of Eddie Felson’s. (There was equally for Scorsese a crisis and then a rebirth

with After Hours after the

commercial failure of The King of Comedy

and the forced abandonment of The Last

Temptation of Christ). Before the two of them can be rejoined in their ‘I’m back!’ finales, there needs to be a

decisive last game of pool, with its round balls on this green carpet.

***

So for

Scorsese’s last film of the decade, his personal project, The Last Temptation of Christ, it is Antoine de Baecque that would

write the Cover Critique (one of his first few, along with Yeelen and The Unbearable

Lightness of Being). It needs to be said: Even though Scorsese is the

American director to get the most covers throughout the Eighties he doesn’t

necessarily reflect a growth at the magazine. He was imposed in the Daney

period and was generally reviewed by his critics. As the decade was progressing

he would be aside from what Toubiana would bring to the magazine and he would

not necessarily reflect the more contemporary American cinema that the younger

new critics were championing.

The Last Temptation of Christ would get its own dossier. Toubiana

brings up the religious controversy surrounding it in his editorial, De Baecque

reviews it, Frédéric Strauss has an essay on Scorsese, Todd McCarthy discusses

its American release, Bérénice Reynaud analyzes Willem Dafoe, and Bill Krohn

has an essay.

De Baecque starts

his Critique with a François de Sales quote,

“As long as we

have two sides to our spirit, one inferior and the other superior, and that the

inferior side never takes over (…), it arrives sometimes though that the

inferior side sometimes succumbs to the temptation and tries to overcome the

superior side.”

“Martin

Scorsese wanted his passion. It has been almost seven years now that he’s been

carrying this cross, sometimes succumbing to temptation (commercial projects,

like After Hours and The Color of Money), but all the while

doing research, accumulating notes, documents and an archive. Today, the

process that he takes, the media attention that he creates, is really

contradictory. This religious polemic against the film displaces its merits as

an exercise in cinematographic theology, it’s a master-work, the key to his

universe.

“All

of his heroes, are forced into a destiny that is thrown onto them in the first

images of the film (After Hours),

Scorsese believes in pre-destiny: This suffering Christ that he pursues

throughout the film, he finishes by catching up to him.

“The

essence of art, for Scorsese, has always been deadly, the stigma (in Raging Bull how De Niro disfigures

himself), these martyrs who find these miracles in Christ… It is due to this

imperative regarding the index of destiny, which is why Scorsese had to be the director of this crucifixion.

A nail digging into flesh is even the synthesis representation of his own

style. But, behind this style, Scorsese wanted to film Christ like an ordinary

man

De Baecque

highlights how Scorsese incorporates a carnal quality in his Christ as he

builds on the writings of Leo Steinberg,

“Scorsese discovers Jesus, gets rid

of his magnificent halo like how he had in the Zeffirelli film. He’s searching

for the most primitive illustration, an expressionism of the counter-reform,

which refuses the baroque pieta, which is reproached by the contemporary integrationist

movement.

“Rarely has a film ever felt to ‘feel’

so profoundly human flesh, to render it in such simple and precise images. This

double transformation of the flesh, which accompanies the voyage of the Christ

figure, this voyage that Scorsese accomplishes through emotions, which he does

while still letting the material speak for itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment