How can a film magazine be challenging? Who

is their readership and what do they want to hear? How to fulfill a demand

without getting trapped in a schema? What movies should be emphasized and how

to write about them? Should there be a fidelity to what has already been published? What should their relation to film history be? And how should print media correspond with digital websites?

So far, to counter this, here at Toronto Film Review, I’ve provided

translations of their recent assessments of the filmmakers Brian de Palma and

Paul Verhoeven. To add to this list here is a new survey of the complete films

of M. Night Shyamalan.

*****

Unbreakable (Cahiers, Jan ’01, N.553),

w/ Cahier Critique by Emmanuel Burdeau, Mon

père ce héros.

The first review of a Shyamalan film in Cahiers was for Sixth Sense, which was rated negatively and relagated to the Critiques section. The

review by Olivier Joyard talks about the platitudes of Bruce Willis, the film's dullness, its inferiority to the work of his contemporaries (Resnais and Egoyan are brought up), and its lack of intellectual merit. This is not a good start for creating a rapport with Shyamalan.

Emmanuel Burdeau, on the other hand, in his review of Unbreakable praises the director. “It

is of no use anymore to asks what is cinema (to answer this question, simply: the

domain of ghosts) but instead one should ask what can cinema achieve: what is the destiny

that it can reserve to these already-deads, to these still-living people whose troubles are on the screen.” And that, “In Unbreakable we find the same religiosity that we found in Sixth Sense. But here it slowly takes

on one of the greatest subjects: progressive disbelief by someone whom the

belief comes from.” Burdeau revises the opinions of Joyard’s

original review: “Sixth Sense,

already, is a response against those that say cinema is dead. Unbreakable takes up this argument and

refines it. First proposition: cinema isn’t dead, because death is

spreading everywhere. Second proposition: it isn’t dead because this death

(life, actually) doesn’t even recognize itself; ghosts in fact still think they're alive (Sixth Sense) and the heroes

are already dead (Unbreakable).” And because of the film's emphasis on the body, Burdeau compares Unbreakable to New Rose

Hotel, Matrix and Mission to Mars.

With this review Burdeau confirmed that Shyamalan is a

filmmaker to look out for and to defend at Cahiers,

and which he would write about on a couple more occasions at the magazine.

*****

Signs (Cahiers, Oct. ’02,

N.572), w/ Cahier Critique by Charles Tesson, Sainte trinité.

Like Bong Joon-Ho’s The Host and J.J. Abrams’ Super

8, Shyamalan's Signs is a film in the shadow of Spielberg’s E.T.. But where with E.T.

the alien came to befriend (at the time, Spielberg expressed that aliens would

not harm), in these films and in Spielberg’s own War of the Worlds aliens are not only unfriendly but

dangerous and violent. Where in E.T.

the alien can be viewed as a cinematic metaphor for growing up and dealing with

the sadness of divorced parents, the presence of vicious aliens in the recent films reflects a darker post-9/11 mood.

Signs

is about Graham Hess (Mel Gibson), a former priest who lives on a farm with his younger brother and two children. He is widowed, his wife

having died in a tragic car crash. There is something supernatural in the air at his Pennsylvania farm; crop circles appearing late at night in

the surrounding cornfields.

Charles Tesson, the reviewer of Signs, is one of the rare older generation Cahiers

writers who still contributes today (eg. Naissances

du Cinéma Indien, N.686) and who is also now the Artistic Director of the Semaine

de la Critique at Cannes. There is also a great article by Burdeau about Signs in the Shyamalan book, Critical Approaches to the Films of M. Night Shyamalan: Spoiler

Warnings.

Tesson begins his review, “The latest film of M.

Night Shyamalan, unlike Unbreakable,

is a movie that is on dangerous grounds, which is about to rupture.” Tesson

describes the filmmaker, “a cineaste rather gullible, skilllful, and blessed in

regards to showing our proposed universe. Shyamalan is the opposite of a naïf

in regards to his usage of special effects and especially that of his mise en scéne. He believes in cinema’s

ability to create tricks and their capacity to fabricate frights.” Tesson

continues, “This great alliance between a real talent of mise en scene and a theoretical understanding of American cinema’s

fictional ability contributes to what makes Shyamalan’s cinema so unique.”

Tesson begins his review, “The latest film of M.

Night Shyamalan, unlike Unbreakable,

is a movie that is on dangerous grounds, which is about to rupture.” Tesson

describes the filmmaker, “a cineaste rather gullible, skilllful, and blessed in

regards to showing our proposed universe. Shyamalan is the opposite of a naïf

in regards to his usage of special effects and especially that of his mise en scéne. He believes in cinema’s

ability to create tricks and their capacity to fabricate frights.” Tesson

continues, “This great alliance between a real talent of mise en scene and a theoretical understanding of American cinema’s

fictional ability contributes to what makes Shyamalan’s cinema so unique.”

Tesson speaks about the use of the

television in Signs,

“The television is the primary character in

Signs: at the beginning of the film,

the little girl complains that the TV is not working, without understanding

that all of the channels are playing the same image – September 11th.

In front of these flaming towers, any child could have had the same reaction.

[…] This presence reveals the starting point of Shyamalan’s project: after

9/11, the new cinematic fictions are to be created in the reflections of a

turned-off television screen; this is when cinema will be able to regain all of

its rights."

Tesson compares Shyamalan to Spielberg,

“Shyamalan’s universe, like that of Spielberg’s (in this respect, his twin

brother), relies on the denial of sexuality. We have to believe in these

characters that no real libido.” Tesson concludes,

“So what are the signs are sign of? A first

step towards sexuality. A new trinity in the name of the father, the son and

the extraterrestrial where the family can recompose itself and the paternal function

can regenerate. And where are the women in all of this? Between the daughter

who places her glasses of water all over the place and the mother who dies and

looses all of her blood, the liquid hypotheses is quickly consumed.”

*****

The

Village (Cahiers,

Sept. ’04, N.593) w/ Cahiers Critique by Jean-Pierre Rehm, Le village est-il damné?, and a Contrechamp by Emmanuel Burdeau, Stupeur et enchatement.

There was a documentary that came out to

accompany The Village, which

is The Buried Secret of M. Night

Shyamalan. It is strange because one are never quite sure if it is

meant to be taken at face value (the press material makes it especially

confusing), but either way, it highlight many themes that are apparent

throughout Shyamalan’s films, and brings up relevant biographical

points.

The

Village of the film's title is a nineteenth century

community whose inhabitants are horrified by a murderous monster living in the surrounding forest. There is something about the production design

and its isolated community that is haunted by mysterious spirits, which is similar to Lars von Trier’s Antichrist and Carlos Reygadas’ Silent Light and Post Tenebras Lux.

Jean-Pierre Rehm, like Tesson, is another

old Cahieriste who now programs at the

FIDMarseille film festival. In his close reading of the film, which

references the Greek classics, he sees the film as a work of social criticism.

“To be a professor of American history,

what filmmaker’s ambition today is to do that?” Rehm asks at the

start of his review, “The one, as it seems, who

claims it the least.” The Village

with its love story, production design, costumes, casting, and cinematography

is, “evidently and slyly, grand and understated, Shyamalan’s latest fairy tale.”

On the use of horror in the film Rehm

writes,“The Village is economic when

it comes to creating terror: no special effects, little is hidden, nor does the

narrative stall, in it the Grand Guignol remains in the background, and the story reveals itself in scenes of expeditious explanations.” Rehm

continues,

“The

origin of the fear, which is revealed to the audience simultaneously as it is

revealed to the blind heroine, is fear itself. It is the red berries that are

part of this conspiracy theory, that bring about this danger which is a

creation of the Ancients, these Amish actors, as a way to preserve their

project: to isolate themselves in a clearing of innocence and to isolate

themselves from the world and its corrupt cities.”

“The

origin of the fear, which is revealed to the audience simultaneously as it is

revealed to the blind heroine, is fear itself. It is the red berries that are

part of this conspiracy theory, that bring about this danger which is a

creation of the Ancients, these Amish actors, as a way to preserve their

project: to isolate themselves in a clearing of innocence and to isolate

themselves from the world and its corrupt cities.”

The

Village's setting is a fictionalized spatial and temporal one that

becomes a “lesson in dramaturgy.” For Rehm, “Brecht, has finally landed in

the American culture industry, and teaches about the necessary critical

distance.” And he continues,

“Here it is, placed at the heart of suspense,

that he tells us: the tale the most sober and poignant is only an illusion

destined to create a change. To substitute a real violence for a fabricated changes everything. Because to

substitute an uncontrollable violence for another one, real and controllable, that is why the Ancients decided to escape. The real world that is

discovered at the security booth when the chief is reading the newspaper is even more violent.”

For Rehm,

“The fiction is an enclosure, not because

it is real but because it is presented as the actuality. But do we know this?

Since Aristotle this has been said. Does it scare people? Not necessarily. If

it is like the difference between The

Manuscript Found in Saragossa or Brigadoon

or other baroque novels, the fiction is less menaced by the commonplace

violence of the surrounding world, but instead comes from the suffocation of

its utopia, the falsity of its magic, and the disintegration of faith itself.”

Rehm brings up the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben to speak about the

politics of the film,

“This is why even though the village is

supposed to be a model of the real, as the chief security speaks about, there

are no planes allowed to fly over the forest, this is nothing but a zone of

non-rights. This territory has become an invisible backstage and with its

surveillance it becomes a sort-of Guantanamo in the rural country. It is no

longer against the exceptional, but a territory constantly in a state of

exception. A state that ceases, like is written by Agamben, “d’être ramené à une situation extérieure et

provisoire de danger réel et tend à se confondre avec la norme même.””

Rehm brings up contemporary events in

relation to his reading of the film,

“The

Village is a bittersweet account of an American seized within its origins

mythology that is completely artificial and that is trying to understand the

reasons why the state incarcerates. Where someone like Michael Moore heavily

plays the Zorro character, Shyamalan prefers the plasticity of a strong fable:

set in 1897 (which can be seen on the tombstone in the opening sequence) to

today, from the stories to its origins, from the western to the pitiful scenario created to

invade Iraq for weapons of mass destruction. These arms, each spectator must

understand are their own and it is the world outside of the village.”

In Rehm’s conclusion he tries to tie

everything together (admittedly, in a complex way, and I’m not sure if I’m

doing his rhetoric justice),

“What kind of boss is then the filmmaker?

Here like before, Shyamalan needs to mystify the options to then pick an

intermediate location. His chief security character, a modest role but an

important one, puts a sense of scale to what Jacob is doing. The Walker

professor teaches history and all of the children listen to him. But there is a

troubling wind that is abounded. The wind continues to agitate the trees of this

Pennsylvania forest where the leaves on their branches can no longer grow. This

troubling atmosphere blows with it a renewed complexity, and where the

particulars are in front of us to see.”

***

Burdeau in Stupeur et enchantement begins, “A major filmmaker: M. Night

Shyamalan, revealed himself to be when he released The Sixth Sense. Since then this evidence is evidently confirmed in

Unbreakable, Signs and now The Village.”

“In

four films, Shyamalan has reignited the beauty, which has for a long time has

been neglected, of decoupage,” writes Burdeau, “But if this was it, grammar and

story-board, Night would only be a master of an art, which isn’t that

important, that of a competent craftsman. But, to our surprise and happiness,

there are two elements that are important to the logic of his “pure cinema.””

These two qualities are, “wild comedy and dry irony but which is understated and where the summit of this

is the jeweler scene in Sixth Sense,”

and, “an extreme slowness. In Shy’s films there is a petrified burlesque, a

terrible weight that belongs to his creatures and somnambulist, more so than

his ghost […] These are films that are dressed in heavy cotton, and it is a

cinema which is slowed down. The suspense is decomposed with each new image.”

What is the function of the comic and the

slowness? “It is to highlight but to wrong, accentuate and to delay revealing

its complex mystery. We have learnt that with Shy, especially when his films

are starting to reveal themselves, and then when they start to shine, that he

organizes each shot like a clue within a larger enigma where only the outcome

will reveal its true purpose.” Burdeau continues, “Let’s call what he does stupor, a word that brings together his

comic tendencies and the slow-burn. Double stupor: a camera that lingers upon a

devastated landscape, the people that are looking out at it: eyes wide open,

standing still, in awe.”

Burdeau’s great conclusion,

“With Shy, this stupor is everywhere, and

it is with it that his cinema carries the promise of being about more than just

mise en scene. It renders the viewer

weak as a way to save them; we can feel it as we watch the screen. And just

like the fake costume-drama of The

Village this common interest, which asphyxiate and seduces, which brings us

closer and farther apart, talks about something extremely precise: this weird

gathering, talks about the intimate trouble that connects us today to images."

*****

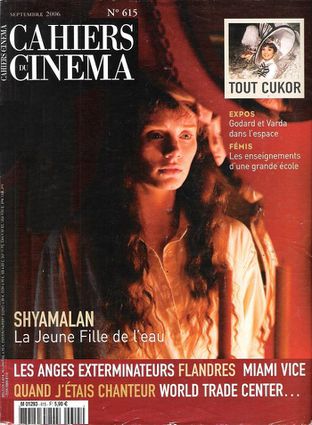

Lady

in the Water (Cahiers,

Sept. ’06, N.615) w/ Événement Cahiers Critique by Jean-Philippe Tessé, Rire et ravissement.

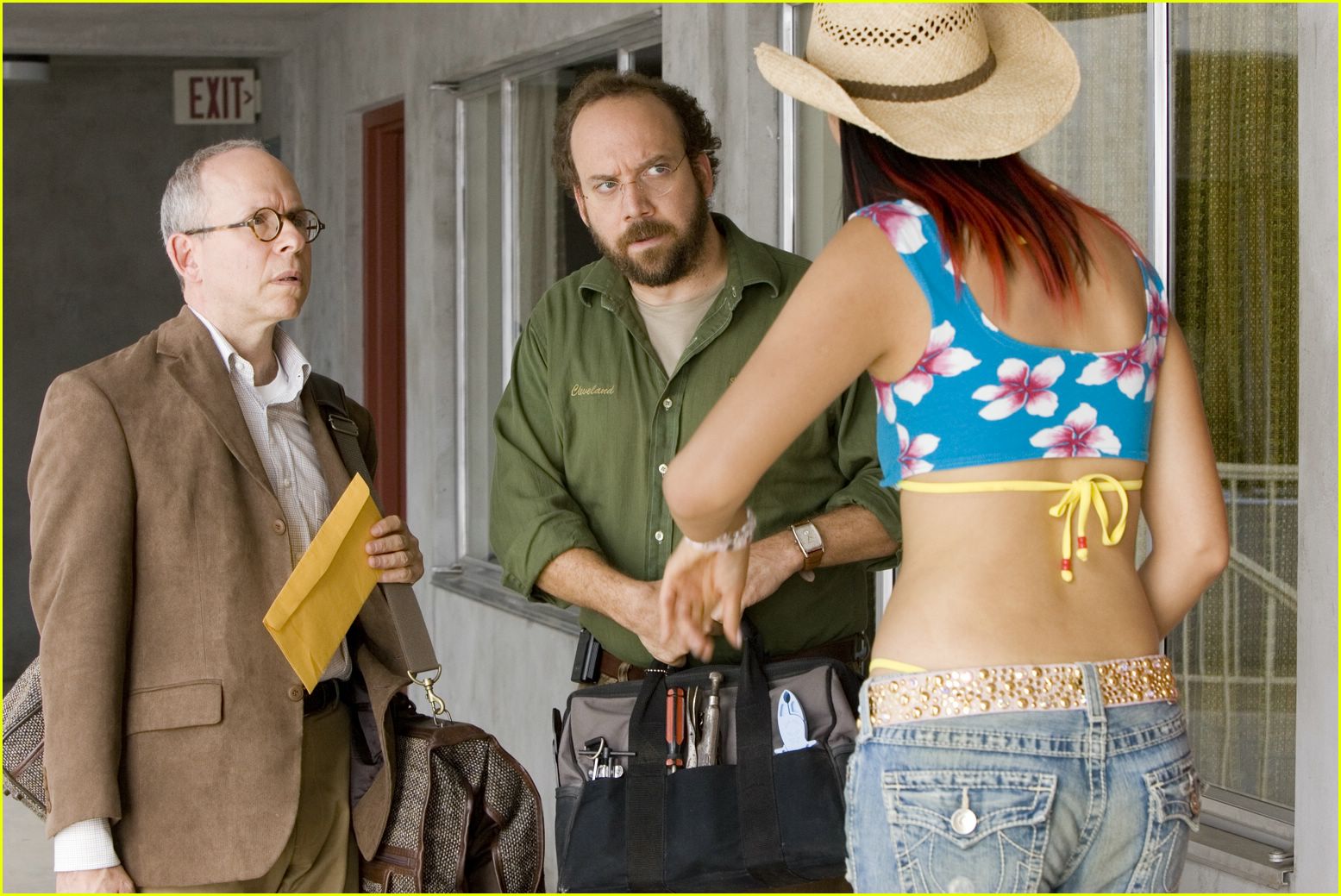

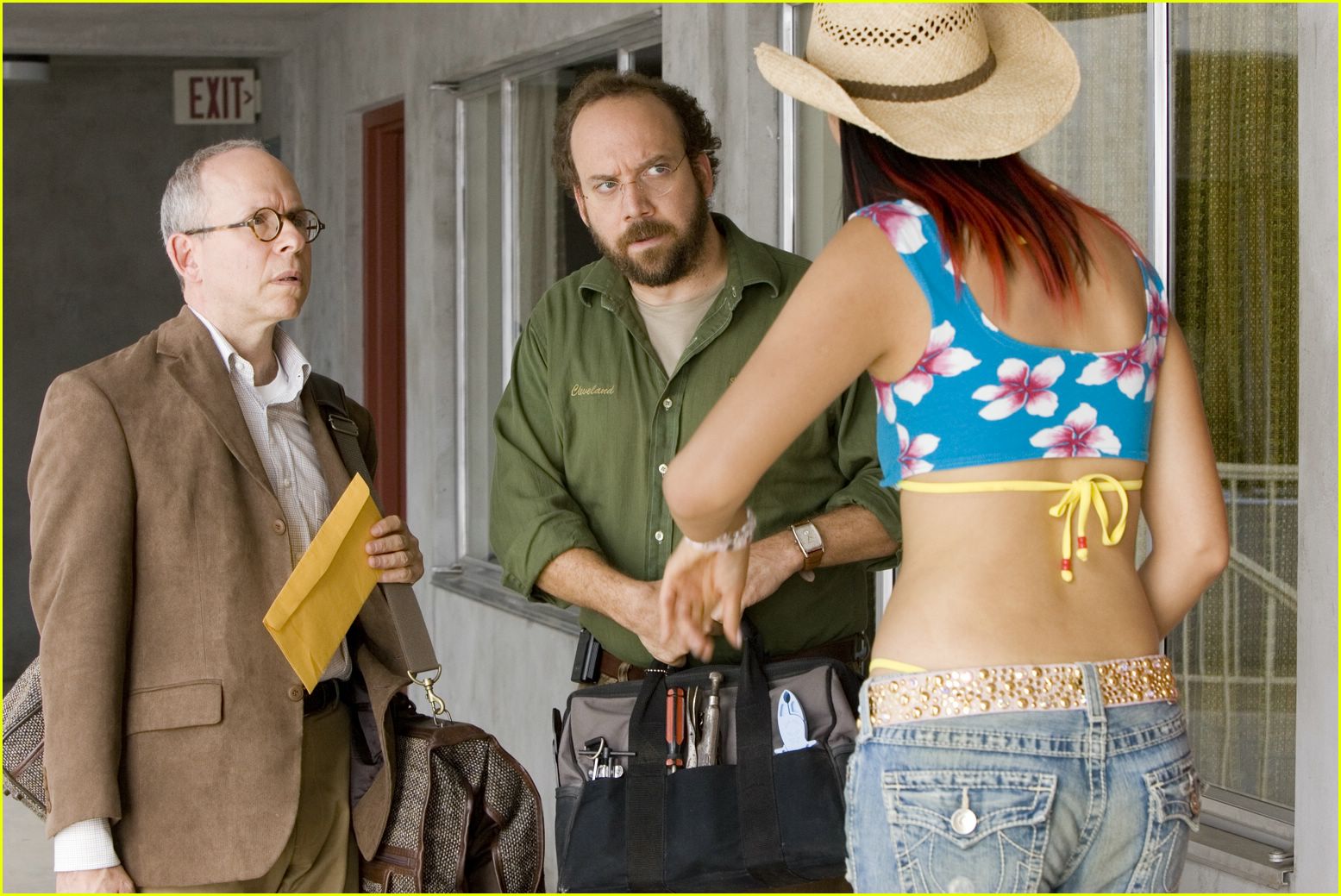

Lady

in the Water is perhaps the most clear and unpolluted

Shyamalanesque vision and the most representative of his imagination and burlesque. Inspired by a childhood

fairy tale he invented for his daughter (and which he would also produce into a book)

it is perhaps his funnest and most entertaining film. And amongst the

impressive special features on his DVDs (which includes his early teenager

short films, and lengthy making-of docs) the behind the scenes of Lady in the Water is maybe his best

(with Sixth Sense, The Village and The Happening following).

Lady

in the Water is the only Shyamalan film to make it

onto Cahiers’cover page and its

review by Jean-Philippe Tessé, who is now the joint chief-editor, clearly

articulates what the magazine admires in Night's films. Tessé contextualizes

Shyamalan’s place in the magazine in his intro:

“The enthusiasm we have at Cahiers for the cinema of M. Night

Shyamalan since his breakthrough into Hollywood will not diminish with Lady in the Water. The laughing at it

by some people will not change what we think.

Simply because it confirms the certitude of finding in Night’s films a

cinema of constant action. Just because it places this within a grotesque fable

with crazy theories, we can’t help but be ecstatic because we place Shyamalan

as the cineaste le plus farfelu de son

temps. His use of comedy is the key to enter into his films.”

In the review the impressive set (the swimming pool motif which was anticipated in Unbreakable) and décor are acknowledged. But

more importantly Tessé writes,

“The encounter with an entity that is so

radically strange is for the filmmaker the privileged motivation for him to

make these fictions. That which comes does not bring with it order, but comes

in the marvel of itself to create these new connections, they are strange

unknowns. Shyamalan films this encounter like nobody else, the moment of pure

newness, and he does it in the most simple of ways, by letting things just be

there, framing the shot in its after-moments.”

For Shyamalan, “there is something that you

need to be ready for his films, which is that of amazement, if you want to enter his game.” Tessé

continues,

“It is by replaying indefinitively this primitive scene of amazement

that Shyamalan was able to find a style. He hasn’t really reinvented

storytelling (though his storytelling grammar is unique to him alone) but

instead he has redefined the fantastical. To say it differently: there is a

pact between the spectator of a Tourneur film, that believes in supernatural

forces, and the person who doesn’t, or who hasn’t adjusted their belief system

to allow for it [...] Nothing else interests Shyamalan, not the ravaging

twists that end some of his films, nor metaphors that we want to read into some

others, nor the ways that the fantastic is manifested: Nothing else interests

him then this opening, this brutal change of coordinates, a total upheaval of

perspective.”

Tessé also writes about how “the scene

captures this stunned response, that dictates everything: these scenes of

action, that go in unexpected new directions, time which is standstill, and the

tone of the scene is infinitively comic.” And after bringing up some

farfetched scenes in the film, Tessé acknowledges their ludicrousness, “You

would be right, they are aberrant. Welcome to M. Night Shyamalan, cineaste and

joker.” And this combination, as Burdeau also elaborated on, Tessé sees as “the

alliance stunned-comic can be described in one word: burlesque.” Tessé expands, “Shy is a burlesque, which is a primitive category, who dreams of

being a fabulist full of humor and that is when he is at his best: when he is

being comic.”

Tessé also writes about how “the scene

captures this stunned response, that dictates everything: these scenes of

action, that go in unexpected new directions, time which is standstill, and the

tone of the scene is infinitively comic.” And after bringing up some

farfetched scenes in the film, Tessé acknowledges their ludicrousness, “You

would be right, they are aberrant. Welcome to M. Night Shyamalan, cineaste and

joker.” And this combination, as Burdeau also elaborated on, Tessé sees as “the

alliance stunned-comic can be described in one word: burlesque.” Tessé expands, “Shy is a burlesque, which is a primitive category, who dreams of

being a fabulist full of humor and that is when he is at his best: when he is

being comic.”

To also note about Lady in the Water, the book The

Cookbook by the Night character in the film which he describes as “it is

actually about my thoughts about all of our cultural problems,” and along with

the child psychiatrist character in Sixth

Sense, seems to anticipate the book Shyamalan is about to publish Schooled: The Five Keys to Closing

America's Education Gap about the high-school educational institutions in

Philadelphia.

*****

There are some other think pieces about

Shyamalan that have appeared in Cahiers

aside from their reviews. The important piece is Années

Hollywood: Shyamalan, Sodergergh, Penn, Mann, Spielberg, Eastwood

(July-August ’06, N.614). In this issue the editor of the time Jean-Michel

Frodon has a good editorial, Bouger les

lignes, Stéphane Delorme has a good overview of contemporary Hollywood, Sur Les Auteurs d’Hollywood, and Hervé

Aubron has an article, Shy en miroir avec

Mann, which compares the films of M. Night Shyamalan with the films of

Michael Mann.

There are some other think pieces about

Shyamalan that have appeared in Cahiers

aside from their reviews. The important piece is Années

Hollywood: Shyamalan, Sodergergh, Penn, Mann, Spielberg, Eastwood

(July-August ’06, N.614). In this issue the editor of the time Jean-Michel

Frodon has a good editorial, Bouger les

lignes, Stéphane Delorme has a good overview of contemporary Hollywood, Sur Les Auteurs d’Hollywood, and Hervé

Aubron has an article, Shy en miroir avec

Mann, which compares the films of M. Night Shyamalan with the films of

Michael Mann.

Another good article appeared in

their Les Meilleurs Films des années 2000

issue (Jan ’10, N.652) in the Cinq

cineaste pour les années 2000 section and it is written by Bill Krohn (I

will hopefully translate that in its entirety at a later date).

I’m not going to discuss the films that Shyamalan

only contributed the story too, or screenplay, since he did not direct them so they do not

reflect accurately his temperament. Stuart

Little has Shyamalan’s water motif and his outsider figure is literalized

as a mouse, and Devil has elements

of the supernatural and family trauma (and a great Joshua Peace performance as Detective

Markowitz) but they are minor works and Cahiers

sees them as such.

*****

The

Happening (Cahiers,

June ’08, N.635), w/ Cahier Critique by Emmanuel Burdeau, Tombée de la nuit.

Each time a new film by a director the review in Cahiers reevaluates them by

highlighting what made their prior films good, evaluating the new film, and criticizing their flaws. They are

building upon the earlier reviews written about the director in the magazine and the writer's review is distinct for their own unique writing style.

In Burdeau’s review he acknowledges that Cahiers is a minority when it comes to

appreciating Shyamalan. He then brings up the difficulty Cahiers had to watch in advance The

Happening so that they could review the movie. There was an interview with Shyamalan that fell through, the film was

not playing in the US, so Burdeau ended up having to catch a plane to Spain

to watch it.

And the film deceived him… But regardless,

Burdeau still found interesting things to say about it,

“The spectator is warned,

this new film is another exercise in reading: less an explanation of a text

then a favorable plea for the never-ending activating of reading […] The films

of Shyamalan have no other concerns. Nor other messages. The mysteries in them

cannot be resolved, only translated and retranslated to no end from one

language to another, now in the thickness and within the oscillation of so many

voices.”

“The tone is Shyamalian,” says Burdeau,

“which means that it is hard to pronounce with usual language. Wonderful and cryptic.

Exotic and comic. Cryptic and spiritual. Mischievous and furiously

intellectual. This is a weird kind of structuralism: the film does not

construct an intrigue, it’s happy to measure an advance towards dread and also

the pleasure that goes into action when there is an intelligence to the

happenings that are put forth into action.”

Burdeau: “I insist: this isn’t a spectacle,

it’s a lecture; it isn’t about the action, it’s about thought; it isn’t a

screenplay, it is a fable.” And, “like in The

Birds which is the inspiration for all of Shyamalan’s films, the

catastrophe is like the magical resuscitation for the dysfunctional family.”

Burdeau also compares the haunted house scene to Indiana Jones.

But Burdeau sees a fault in the film, “The

decision to not give an explanation to the happening as anything but nature is

the films biggest problem, the biggest rupture with Shyamalan’s other films.”

He goes on, “What is lacking in The

Happening is not an explanation or even more action scenes. What is lacking

is dialogue that would resonate with the smallest of detail and the whole.

Shyamalan is a grand painter of the everyday because he saw the larger picture,

the text of all the other texts.” And that the environmentalist message of the

film is simple.

Burdeau gives Shyamalan the benefit of

the doubt, “This disaster of a disaster film might have something to do with

its production that went through several producers.” Burdeau hopes that

Shyamalan’s next film will be better, and as the little girl on the bus turns

around, her backpack reveals a graphic for Avatar:

The Last Airbender.

*****

The

Last Airbender (Cahiers,

Sept. ’10, N.659) w/ Répliques by Vincent Malausa, Une Page Blanche, and an interview, Air Shyamalan, by Malausa and Jean-Sébastien Chauvin.

This is an important issue in the

development of Cahiers since its new

chief editor took the role late in 2009. There was at first an uncertainty of how to direct the magazine (e.g. small

polemics: an anti-Fellini stance, destroying Funny People etc) but with each passing year the magazine's positions became stronger. The most vocal stance is

perhaps their railling against the petrification of severity in contemporary art-house films,but

they are also known for their championing of American films and world cinema.

What makes Cahiers N.659 so special, with a still of Antony Cordier’s Happy Few on its cover, is

its Événement, Nouvelles utopies du

cinema francais. In the issue Delorme speaks of and is critical

of the trend in French cinema of “mettre

en scene des utopie.” Where he sees in these idealist utopias an escape of

the urban and its realities, which for a long time has been the emphasis of

French cinema. Delorme asks, “What direction are these fictions going in? Why a

closure, which takes place in the form of a denial, to substitute for another

closure, that of the social?” Delorme

prefers Des homes et des dieux

against Homme au bain and Happy Few.

This idea of the utopia of French cinema is

going to be something the magazine will return to. The idea of taking a position and then being commited to it will start to be more important in Cahiers after this issue. This is articulated through the magazines stronger emphasis on their use of meta-textual references. By referencing other articles and other issues

there is a stronger interconnection between each issue and this

bond is making the magazine more dense with connections, more clear and

thorough with its argument, and more convincing and interesting.

In Cahiers N.659 the magazine praises Uncle Boonme by Apichatpong that would make it on their Top Ten Films of 2010. There are also similarities between the Apichatpong film and Shyamalan's The Last Airbender

with their use of nature and spirituality. Apichatpong

has also acknowledge his admiration of Shyamalan. Through how the directors in them present folliage there is a connection between Boonme,

The Happening and John Boorman’s The

Emerald Forest.

To return to The Last Airbender: Malausa isn’t necessarily convinced that it is

a major work and describes the film as a “visual kitsch cocktail that mixes the

wuxia with the teenage film and Lord of Rings

to create a digital cosmologic folly.” Some highlights of the film include:

“its opening in the radiating clarity of Greenland that can be seen as the blank

canvas that Shyamalan will unleash his imagination,” and Malausa compares the energy of

the child to that of Tintin. The film has some other interesting qualities

like the dichotomy between Aang and the son of the fire god, which can be seen as two sides of

Shyamalan’s character: one wants to create magic and mystery while the other wants

to fulfill his duties (ie. commercial imperatives). Malausa ends the pieces by

highlighting Airbenders tragic quality that connects it to Shyamalan’s other

films, “The Last Airbenders

articulates around this idea of tragedy which is that of children, who are condemned to

carry the weight of the world of their shoulders, and have to start acting like

adults.”

To return to The Last Airbender: Malausa isn’t necessarily convinced that it is

a major work and describes the film as a “visual kitsch cocktail that mixes the

wuxia with the teenage film and Lord of Rings

to create a digital cosmologic folly.” Some highlights of the film include:

“its opening in the radiating clarity of Greenland that can be seen as the blank

canvas that Shyamalan will unleash his imagination,” and Malausa compares the energy of

the child to that of Tintin. The film has some other interesting qualities

like the dichotomy between Aang and the son of the fire god, which can be seen as two sides of

Shyamalan’s character: one wants to create magic and mystery while the other wants

to fulfill his duties (ie. commercial imperatives). Malausa ends the pieces by

highlighting Airbenders tragic quality that connects it to Shyamalan’s other

films, “The Last Airbenders

articulates around this idea of tragedy which is that of children, who are condemned to

carry the weight of the world of their shoulders, and have to start acting like

adults.”

Air

Shyamalan is the first interview with Shyamalan

in Cahiers. The interview is interesting as Shyamalan talks about the minimalism of filming nature, how The Happening was inspired by Village of the Damned (“I saw this film when I was twenty and it has never left me.”), about the special effects in the film, faith in the medium, his multiculturalism, that his favorite filmmakers are Hitchcock, Kubrick and Kurosawa; talks about courage and terror, and his admiration for Agatha Christie and Planet of the Apes.

Even though Night is a championed director

at Cahiers they acknowledge the flaws in some of his films, when they deserve it. What

is the big difference between Cahiers

and how most other critics view Shyamalan’s work is that Cahiers approach his films with a generosity instead of

condescension. Shyamalan's films necessitate the viewer to take a leap a faith to best appreciate their unique and mysterious vision.