For Andréa Picard

For Andréa Picard

“And there will be poets like this! When the eternal slavery of Women is destroyed, when she lives for herself and through herself, when man – up till now abominable – will have set her free, she will be a poet as well! Woman will discover the unknown! Will her world of ideas differ from ours? She will discover strange things, unfathomable, repulsive, delightful; we will accept and understand them.”

-- Arthur Rimbaud in a letter to Paul Demeny, May 15, 1871

I have had many experiences viewing films that have expanded my consciousness. The films of Paolo Gioli and Joseph Cornell come to mind, as do Welles, Warhol, Rivette, Antonioni, and, of course, Rossellini. These artists have all offered me tremendous experiences. The most important experiences I’ve yet had, however, have been through the work of women filmmakers. The films of Catherine Breillat, for example, have impacted me immensely. From her I learned, among other things, that feminism could be as faulty as chauvinism. By that I mean that within chauvinism, a woman must be a man’s version of a woman, but within feminism, a woman must often be a woman’s version of a man. (To this I’ll add that from her films I learned that the only thing I truly know about women is that I’m not one.) From that I understood that all things and all circumstances must be viewed with respect for their own individual content. This, I find, is achieved nowhere better than in the films of female directors.

Films with this approach that immediately come to mind are Glimpses of the Garden and Lights by Marie Menken. In these films there is a sensitive observation and respect for the inherent content of the subjects of these films, in this case a garden and lights. These things do not have their own consciousness, of course, but they are still accepted and respected by Menken if only because they exist. The presence that permeates these films can also be sensed, in relation to performers this time, in the films of Agnès Varda and Ida Lupino, particularly in the climactic scenes of the latter’s The Bigamist and The Hitchhiker. Chantal Akerman and Tacita Dean, too, take this approach to beautiful extremes with the huge, spiritual gulps of time and subject in their work. To elaborate on this further, however, I will touch on what I find to be one of the finest examples of this particular kind of filmmaking, the films of Joyce Wieland.

Films with this approach that immediately come to mind are Glimpses of the Garden and Lights by Marie Menken. In these films there is a sensitive observation and respect for the inherent content of the subjects of these films, in this case a garden and lights. These things do not have their own consciousness, of course, but they are still accepted and respected by Menken if only because they exist. The presence that permeates these films can also be sensed, in relation to performers this time, in the films of Agnès Varda and Ida Lupino, particularly in the climactic scenes of the latter’s The Bigamist and The Hitchhiker. Chantal Akerman and Tacita Dean, too, take this approach to beautiful extremes with the huge, spiritual gulps of time and subject in their work. To elaborate on this further, however, I will touch on what I find to be one of the finest examples of this particular kind of filmmaking, the films of Joyce Wieland.

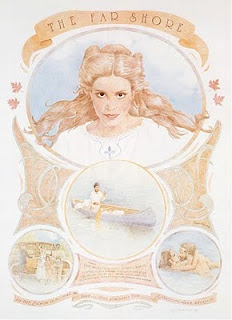

In her short work, such as Sailboat, Birds at Sunrise, or Rat Life and Diet in North America, there is a constant presence of acceptance. Even in Barbara’s Blindness, there seems to be an acceptance of the found film footage she is editing. In terms of acceptance itself, anyone who has experienced either side of true acceptance knows the courage the act takes. It calls for a steely nerve and a concrete, dignified sense of self. This authentic sense of acceptance is very present in her one feature length film, The Far Shore, although in this case with several other elements also at play. Too “normal” for the avant-garde and too “weird” for the mainstream, The Far Shore is a generally unknown and unseen film that easily stands beside her greatest accomplishments as an artist. Like her quilt works, it intelligently and subversively reclaims something dismissively relegated to the domain of the woman. In the case of the quilts, it is “woman’s work” and in the case of The Far Shore, it is the “woman’s film” – the melodrama. Within the structures of this genre, she speaks to the nature of the artist in Canada, the relationship between Anglophones and Francophones, but most importantly, the place of the Free Woman (in a mental and emotional sense, at least) in modern society. She does this in a number of ways – through abstraction and satire and through her tremendous compositions – but mainly through that very essential and fine edged acceptance. Most notably, it is visible in the performances, or more accurately said, the performers. This is due to a very intricate relationship that, I think, lies at the heart of these films. In The Far Shore (and in many of the other films mentioned here), there are often infinitesimally small gestures visible in the performers that are very affecting. They are of such consequence because they are not emanating from the performers within the artificial construct of the film, but from the person, the human, reacting to the artificial construct of the film. This is very complex, and would be regarded by less sensitive and perceptive artists as mistakes, whereas they are, in fact, triumphs. The main thing this approach accomplishes is that it renders the elements of the film as subjects rather than objects. This permits them dignity, autonomy and true vitality. These acts are not of forcing things into existence, but of being aware of what will exist and permitting it to by creating the proper conditions. It’s the reverse of the typically assumed direction; backward, like Ginger Rogers to Fred Astaire. It’s similar, too, to that tremendous, almost Franciscan effort that it takes to actually see the sky – to look up and allow the sky to exist and not have it blotted out by your assumptions. It’s a very selfless act, a sublimely passive one, and, I will say, an importantly feminine one.

I am, by no means, implying that only women are capable of this approach. The films of Rossellini in both film and television could easily be said to have these elements; as can works like Maurice Pialat’s L’Enfance Nue, Jacques Demy’s Model Shop or certain works by Nathaniel Dorsky, like Summerwind. All people have these capacities within them -- like Lorca said, “Mi alma de niña y niño” (My soul is both male and female). Though, in my experience it seems that directors who are women can most wholly and organically accomplish this effect. Experiencing works like these that take such an independent mind have been extraordinary for me. This is in part because they are so delicate, and in part because they are so rare. Until Rimbaud’s statements on the female poet are true to a greater extent, however, the last word will come from one of these rare, courageous and important Free Women: “There should always be a giving to the senses and an enrichment of the soul.... It's a way to tell the truth but it's also a way to open vision, how to see.” (Joyce Wieland).

Daniel Gallay

Further Reading: Johanne Sloan’s recent Canadian Cinema monograph on Wieland’s The Far Shore is an invaluable resource for information on the film. Cinematheque Ontario’s monograph on Wieland is also an excellent source of information on the artist’s work in film. Both are available at the TIFF.Shop at the TIFF Bell Lightbox.