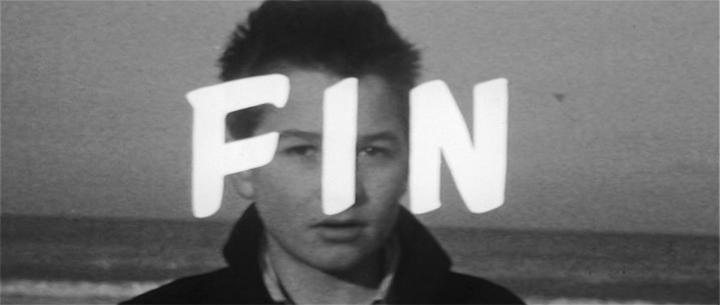

To coincide with their recent François Truffaut exhibition

the Cinémathèque française put together an amazing website where they compiled

a variety of Truffaut quotes. It’s described as “a website in the form of an

intimate journal” and the quotes come from a variety of classic essays and interviews,

which includes text, audio and videos (some of this rare footage is also

embedded in the site). They’re full of fascinating insights on all of his

films, how they were made, his personal obsessions, and the work of his many

collaborators. The mise-en-page of Truffaut par Truffaut is gorgeous as the

site, building upon the Cinémathèque’s extensive Truffaut’s Films de Carrosse

archive, is full of rare pictures of the director, annotated documents, and

interesting promotional material. Each new entry, which was slowly launched

over a couple of months, opens with a unique banner and a brief resume of the

previous chapter. It’s wide reaching as it goes from his beginnings and his

disadvantaged childhood through to his early years as a film critic at Cahiers du Cinéma to his emergence as an

innovative filmmaker alongside his nouvelle

vague peers and finally to his steady career at Les films du Carrosse. The

15 sections of Truffaut par Truffaut are:

L'école buissonnière, Premiers souvenirs de cinéma, André Bazin ou l'initiation

à la critique, La passage à la réalization, Nouvelle vague, Les Films du

Carosse, Série noire, Série blême; Antoine Doinel, moi et mon double; Fahrenheit 451, un tournage difficile;

Cinéaste des passions, Acteur, Tournages, Filmer les enfants, Musique et

chansons, and Truffaut/Hitchcock.

In it you can read about Truffaut’s troubled childhood and

skipping class as a youth to go to the cinema (material he would draw from when

he would make Les quatre cents coups).

On these matinee screenings in the Forties Truffaut describes how the first movie

theater that would open would receive a large group of kids who just wanted to

get out of sight and off of the streets since they were skipping class. It

would be in this period where Truffaut and his friend Robert Lachenay, through

their film club Cercle cinémane, would get to know Henri Langlois and Bazin. Truffaut

discusses how he first read Bazin in Revue

du Cinéma – a critique of Monsieur Verdoux – and when Truffaut’s

stepfather discovered that he ‘borrowed’ funds to run his film club and he brought

him to prison (a similar experience that created guilt to what happened to Hitchcock) and that it was Bazin who got

him out and who he would stay with afterwards, and who would get him a job at Travail et Culture. Bazin, and Jean

Genet surprisingly, would also help Truffaut when he was trying to get out of

his military service. Truffaut would dedicate Les quatre cents coups to Bazin.

On his youthful cinephilia, Truffaut discusses seeing Citizen Kane around 20 times by the age

of 13, and that, “Suddenly, I realized

that a film could be written like a novel,” and that in this period, he

denounced French films (“a little excessively”) in contrast to the star power

of the American actors. He started writing serious film criticism in 1953 and

his famous essay on the politique des

auteurs (Cahiers N.31), which

emphasizes the director’s worldview as illustrated through his body of work,

and a certain extremity in taste, would be an important early influence at the

magazine.

On what makes a good critique, around this time, Truffaut

writes,

“It has to be intellectual, since it necessitates a reflection on the films. To comment upon them. But what to write! One can’t just be washed over by the images, you really had to analyze its scenario. This was a real important step for me: I started to search for why a film wasn’t entirely interesting, why the first half was good and the second went into these weird directions. For the first time, instead of saying ‘it’s good!’ or ‘it’s bad!’, I started to ask myself why.”

On Bergman’s Summer

Interlude, “it’s the film that gave me the impression that anyone could

write dialogue, or at least that I could.”

Meeting Rossellini in 1951, and working with him for two

years on scripts (which were never made) greatly contributed to Truffaut

wanting to become a filmmaker. It was Rossellini who would turn Truffaut a

little away from American films in favor of simplicity, clarity, and logic.

Truffaut made his first film at the age of 27. His first short film, Une visite (there is a picture of its

script on Truffaut par Truffat), is a

lost film and is described as being ‘not good.’ Alain Resnais even proposed to

re-edit it. But as Truffaut says his first official work is Les Mistons working with Gerard Blain

and Bernadette Lafont. Truffaut describes this short-film working best when it

was closer to a documentary on the boys. Truffaut got money from Pierre Braunberger to make

a documentary on a flood, which would become Une histoire d'eau and would be edited together by Godard. It was

“copiously mocked!”

Truffaut’s definition of the nouvelle vague,

“The nouvelle vague never had an aesthetic program, it was simply a tentative to renew a certain independence that was lost around 1924, when films became to expensive, a little before the talkie. In 1960, for us, to make a film, it was to imitate D.W. Griffith, who made his films under the California sun, even before the birth of Hollywood. In this period, the directors were all really young. It’s crazy to know that Hitchcock, Chaplin, Vidor, Walsh, Ford and Capra all made their first films before the age of 25. It was the work of youthful boys, as it should be. Therefor the youth need to take over, like Guy Gilles or Lelouch, or even younger people, cameras in hand, ready to get in a helicopter or even to trek the Amazon.”

On Tirez sur le

pianiste,

“In one way, I made Tirez sur le pianiste against Les quatre cents coups. For my second film, I felt there was a lot of expectations, from this public who only go to the cinema twice a year. I wanted to please those are really passionate about the cinema and only them, to re-route those who liked the earlier one. I refused to be the prisoner of this success, I avoided the temptation of making an ‘important film’. I turned my back on what was expected from me, and I took up as a rule to follow my own desires… And Tirez sur le pianiste also gave me the occasion to show that I was formed by American cinema.”

On Jean Renoir’s influence,

“I dedicated La Sirène du Mississipi to Renoir because, the way I improvise with the actors and dialogue, it was always him that I thought about. In front of each difficulty, I always asked myself: “How would Renoir get out of this?” I don’t think that a filmmaker should ever feel alone if he knows the thirty-five films of the auteur of La Règle du jeu and La Grande illusion.”

On growing up,

“Up to L'Enfant sauvage, when there were children in my films, I always identified with them, and then, for the first time, I started to identify with the adult, the father, all the way to the point, that while I was finishing editing it, I decided to dedicate it to Jean-Pierre Léaud, because this passage for me, starting to become clearly evident. I thought a lot about him and our earliest work while I was making this film. For me, L'Enfant sauvage, it’s also my passage towards adulthood. Up to then, I always considered myself an adolescent.”

On Hitchcock and their interview book,

“I told myself that if he accepted – for the first time – to answer systemically my questions on his art and his productions, that this book could produce a positive change in how American intellectuals see him… His oeuvre is both commercial and experimental. It’s as universal as Wyler’s Ben Hur and as confidential as Anger’s Fireworks. A film like Psycho, which was incredibly popular, is just as free and savage as certain youthful avant-garde films made on 16mm. The scale of North by Northwest, the tricks of The Bird have the poetic qualities of an experimental cinema as practiced by the Czech Jiří Trnka with his marionettes. I’m convinced that Hitchcock’s work, even on those that refuse to acknowledge it, influences, for a while now, all of world cinema. This influence, direct or subterranean, stylistic or thematic, well-done or badly assimilated, has been exercised on varied directors.”

The Cinémathèque, also to coincide with the exhibition,

organized a series of fascinating conferences and published a new catalogue.

Serge Toubiana, the director of Cinémathèque, speaks of his 1980 interview with

Truffaut as a redefining experience, for himself and Cahiers, in understanding cinema’s potential to be both personal

and industrial. This reconciliation with an important figure of the Cahiers project would become a decisive

feature of Toubiana’s Cahiers editorship

starting in the Eighties and it would continue onwards through his editorship, eventual side-projects and his responsibilities at the Cinémathèque. Toubiana would also publish a magnificent Cahiers issue on Truffaut after his

death (Le Roman de François Truffaut),

co-write a biography, and make a documenaty (Portraits volés) on him. In the new Truffaut catalogue (Flammarion) Toubiana also seems to be

continuing a youthful Truffaut tradition by going out with an audio-recorder to

do interviews with Truffaut’s past collaborators on their experiences and how it affected them.

Also there’s great new dossier on Truffaut on the website Feux

Croisés. There Chloé Beaumont, who did a great job writing and putting together

these texts, has an interview with Toubiana, and of note is Oriane Sidre’s

article Truffaut l'acteur.

Truffaut’s spirit is still with us.

No comments:

Post a Comment