Jean re-watched these films from 2007 to 2014 and the

commentaries are all up-to-date from these recent viewings. It’s impressive to see significant entries on films that just came out last year, like Tu dors Nicole, Que ta joie demeure and Mommy.

Jean’s an expert on the subject - having worked in the

industry, is a film critic and the author of numerous books on the subject - and

the book’s historical depth, diversity and taste benefit from this. Québécois

cinema has a richness to it in its representation of its unique culture, and it

has been able to create a stable radio and television industry, which allows

for the rise of smaller, more artistic films in its periphery. The book goes

back to its earliest output in the Forties and then progresses all of the way

to the present.

Jean’s comments can be both positive and negative. Jean

appreciates originality and innovation, as well as works that are rich

historically or anthropologically, while he dislikes simplifications, emotional

manipulation, and miscasting. It’s also impressive for his openness and generosity

towards typically overlooked forms like the short-film, animation and the

experimental genre.

All of the films by the big name auteurs are there, along

with many lesser-known figures and oddities. There are great entries on Denys

Arcand, Louise Archambault, Michel Brault, Gilles Carle, Denis Côté, Donigan

Cumming, Sophie Deraspe, Xavier Dolan, Bernard Émond, Philippe Falardeau, André

Forcier, Simon Galiero, Pierre Hébert, Claude Jutra, Stéphane Lafleur, Jean-Claude

Lauzon, Robert Lepage, Jean Pierre Lefebvre, Arthur Lipsett, Francis Mankiewicz,

Catherine Martin, Norman McLaren, Robert Morin, Rafaël Ouellet, Pierre Perrault,

Sébastien Pilote, Léa Pool, Chloé Robichaud, Daïchi Saïto, Theodore Ushev, Jean-Marc

Vallée, and Denis Villeneuve.

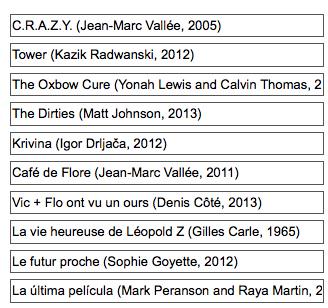

Some of what are considered the best Canadian films are included,

like Mon oncle Antoine, Les Bons débarras, Léolo, Jésus de

Montréal, and C.R.A.Z.Y., which

are relevant to re-watch and to read about, especially with TIFF’s best of

Canadian film poll around the corner (cf. my list, on the right). It includes their popular cinema, as well. Louis Saïa is in

there with Les Boys I, II and III, which are dramatic comedies on Québécois

masculinity and the attraction of hockey. There are also two entries on Jean’s

own films (modestly written about in the third person).

The contemporary generation of directors is present and

there is an impressive inclusion of their early short films. One gets the

impression that Denis Côté, Stéphane Lafleur, and Xavier Dolan are Jean’s

favorite directors of this movement: Côté’s full filmography (except maybe for

some shorts) is analyzed and so is Lafleur’s, whose early shorts Karaoke and then Snooze sound especially interesting.

There are some up-and-coming young directors, like Anne Émond (Sophie Lavoie,

Nuit #1) and even Sophie Goyette makes it in with an entry on La Ronde. Jean writes, “With its solemn

tone, its narrative economy, the unsaid, and its fascination with death,

Sophie Goyette’s film is representative of a major trend in Québécois cinema,

along with Nicolas Roy.”

There are some interesting choices and exclusions too, which

it would be interesting to hear more about their reasoning. The films by its

directors that are made outside of Québéc are typically not included. This is

sometimes strange, as, for example, a film like Café de Flore, which is set in both

Montreal and Paris, isn’t included. While David Cronenberg’s The Brood to Videodrome are included (Jean mentions they got Québécois funding),

even though they are set in Toronto and the broader Ontario area. Dušan

Makavejev’s Sweet Movie starring

Carole Laure is included as one of its most controversial co-productions. It’s

interesting to remember that Don Owen started his career in Montreal (The Ernie Game, Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr.

Leonard Cohen, Notes for a Film about Donna and Gail). Ted Kotcheff’s

important The Apprenticeship of Duddy

Kravitz is there. But so is surprisingly Sylvain Chomet for La vieille dame et les pigeons and Les triplettes de Belleville, which I

guess must have been Québécois co-productions. One would have also liked to have seen more First Nations entries

- Alanis Obomsawin, their most representative figure, only gets one for Incident at Restigouche.

The book traces how the Québécois cinema evolved throughout

its history, what were the films that influenced the subsequent generations,

and what were the connections between its artistic collaborators. In the

entries there is a strong emphasis of the contributions of the National Film

Board in Québécois production, especially as they were based in Montreal. (A

lot of these films you can find on the great NFB website). This accounts for a

big influence of cinema vérité, which Perrault and Brault helped to define with

Pour la suite du monde, on their

fiction films and documentaries. The French New Wave was a big influence in the Sixties, and it’s odd not to see more exploitation films, which blossomed in

English Canada in the Seventies due to Tax Shelter benefits.

The book doesn’t hierarchize the films, though, which, I

think, it could have benefited from. Though Jean has longer entries on the

more important films, I think, an evaluative hierarchy or even a list of their

best films (which, would have gained by more voices) could have added to its

project. But Jean’s evaluations seem to be on point. La vie heureuse de Léopold Z, which I consider the best and one of

the most important Canadian film, Jean writes, “Carle’s use of fantasy, his lightness, and sense of humor

make this film the summit of Sixties young Québécois cinema.”

But, I think, one must say, because not enough people do, that Gilles Carle is the best Québécois, and Canadian, director of all time; and his heir, for sharing many similar preoccupations, Jean-Marc Vallée, the best working Québécois, and world, director living today.

But, I think, one must say, because not enough people do, that Gilles Carle is the best Québécois, and Canadian, director of all time; and his heir, for sharing many similar preoccupations, Jean-Marc Vallée, the best working Québécois, and world, director living today.

Either way, those are only some minor qualms, Dictionnaire des Films Québécois is a major new book for Canadian cinema, and it's rich in insight, fun to read, and accessible to the

general reader. This dictionary is a

must-read for anyone interested in Québécois cinema, along with the regular writing on the subject at 24 Images.

***

Let’s take this review further and look closely at one of

the directors that it features. Why not, for example, examine Jean’s entries on

Jean-Marc Vallée.

Of note are the two entries on two of his short-films, Les fleurs magiques and Les mots magiques. (Though there is nothing on Stéréotypes). The summaries they

include on these films are great since both of these are impossible to find.

Jean describes the two works as family dramas, whose theme is that of the

father-son relationship, and that they are done in Vallée’s impressive

magical-realism style.

At the end of the Sixties, a ten-year-old boy wants his father, whose an alcoholic and violent, to recover from his illness. From his room, where he observes his mother’s anguish and his father’s crisis, he prays to Jesus, observes his flower and wears his good-luck hat, to conjure a better fate for his family.

On the film, which came out the same year as Liste noire, Jean notes that it’s

‘remarkably masterful’, especially in its period detail and use of music (Dinah

Washington’s What Difference A Day Makes),

and it marks Vallée’s first encounter with Marc-André Grondin (who he would

star in C.R.A.Z.Y.) and originates

many themes and style that the director would later develop.

On Les mots magique Jean

describes its story,

Nearing Christmas, a young man visits his father with the intention to give him a letter where he tells him the deepest feelings in his heart. He finds his father unexcited, drinking his beer in front of the television. He imagines telling him his feelings, with the hope of a reconciliation.

Jean writes that these two shorts announce C.R.A.Z.Y and it pursues Vallée’s

interest in father and son relationships, his theme of predilection. Jean is

especially generous towards it, as he describes it as “the richest short

fiction film in all of Québécois cinema history, which explains Vallée’s immaculate

progression, where he plays with emotions but without ever falling into

pathos.”

There are also entries on Liste Noire, which Jean describes as a classic genre film (which

was something rare for its time), and C.R.A.Z.Y.,

which for some reason Jean describes as his second full-length film (it’s

actually his fourth). Jean discusses Vallée’s impressive visual innovation and

use of the soundtrack, along with the autobiographical contributions by its

screenwriter François Boulay. Jean concludes,

“Finally, we are in front of a rare example, in Québéc, of a truly

popular cinema with an ambitious aesthetic dimensions, and which consequently,

also rare, found a unanimity with both the public and the critics.”

***

Since Vallée is going to give a Master Class at the Rendez-vous

du cinéma québécois on Friday, February 27th at 7:30PM it’s worth bringing

some recent news about him.

Éditions Somme toute (again), one of the great publishers of

Québécois cinema books, in 2013 published the script of Vallée’s C.R.A.Z.Y. It’s interesting in it to read

its editor Raymond Plante’s preface, the script, Vallée’s working methods, as

well as to see some of the rare photographs from its production.

On the film Plante expresses his affection for it nicely,

For the most of us, C.R.A.Z.Y. was the film of the summer of 2005, the one that reminds us of memories of a past that wasn’t too far away, it awed us, made us laugh. We saw ourselves in the film. Like how certain songs can mark a season, we hold on to this memory, we believe C.R.A.Z.Y. is unforgettable.

It’s a similar sentiment to what Mathieu Chantelois

describes in his Vallée piece in Cineplex Magazine, “When I told my French-Canadian mother I was going to see a

screening of Wild, a movie directed by Jean-Marc Vallée and starring Reese

Witherspoon, she asked, “Who’s Reese Witherspoon?”” There is something extremely local about Vallée and the personal responses that he gets in Canada are really strong.

The script of C.R.A.Z.Y.

is great (I now want to see an annotated version!) especially as one can

see how much of the film and story is there on the page. It’s interesting to

note, again, that Vallée gets his son Émile Vallée to play his younger self

(just like he would get Cheryl Strayed to do with her own daughter in Wild) as well as to look at the scenes

with the young priest character, who is played by Vallée himself, especially in

light of all of his own following films’ religious themes. It’s also interesting to see what he cut

out, like a scene between Zachary Beaulieu and a psychiatrist. Vallée has

always been a director of understatement.

In the Approche du réalisateur, which is a must-read for any

Vallée fan, he writes, “No matter what the

film, my approach is always the same: to tell a story with the sincere desire

to present the best spectacle possible.” He mentions how for him, a good film, can instill a reflection to see the beauty of life and the world. There is so much on Vallée's methods here regarding every element of the filmmaking process. I can't recommend it enough.

Just to conclude: With the promotion of Wild finished it's worth highlighting some of the best pieces and interviews with Vallée that came out. There is now a confirmation that he's going to adapt The Proper Use of Stars on Sir John Franklin's 1845 Northwest passage, Agnès Gruda had a great piece in La Presse on him L'homme qui pleure, in Variety he discusses his collaborators, there is a great interview with in in MovieMaker, Kevin Laforest put up an old piece where they discuss the influence of Yves Lever on both of them, and the L.A. Times posted a great Oscars roundtable (Wild has a few nominations) with Vallée alongside Miller, Linklater, Marsh, and Chandor.

Vallée's at the heart of things.

No comments:

Post a Comment