The primary research question for this paper is how does the

French sociologist Latour and his theories put pressure on cinema and cinema

studies? This question can be interpreted a few different ways. What

relationship does Latour have with cinema, in terms of the directors that he

has written about and has expressed an affinity towards? Has he been an

influence on any specific directors in terms of his mentorship as a professor?

Has he himself made any films, or acted in any? Does Latour’s cultural writing

in general offer an idea of the aesthetic that he would value in terms of the cinematic?

What about his own artistic and cultural practices? Do they have any cinema-related

value? And finally, does ANT offer a useful concept for analyzing films?

This paper will try to answer those questions by discussing

how Latour has intersected with cinema throughout his career. For example, he

developed personal connections with some filmmakers (Paravel and Green) and his

theories may have had a potential influence on them or vice versa. Latour

himself has made a film, The Tarde

Durkheim Debate (1903/2008), or at least conceptualized it and acted in it. Latour’s writing, curation and

creation (for example, of Paris:

Invisible City) has provided a model for his aesthetic theory as metaphors

for his social theory. Furthermore, ANT offers an interesting perspective to

the analyses of films, most notably the documentary.

Véréna Paravel and Eugène Green

In

recent years, Véréna Paravel, a PhD in Anthropology and one of Latour’s former

students at the École Nationale Supérieure des

Mines, with Lucien

Castaing-Taylor, the director of the Sensory Ethnography Lab (SEL) at Harvard

University, made an experimental documentary on a fishing ship, Leviathan (2012). This was the most

direct connection between Latour and cinema and film studies. Scott MacDonald in American

Ethnographic Film and Personal Documentary wrote, “Leviathan is surprising – its immersion of its audience within the

audio-visual surround... feels not only overwhelming, but quite new in the annals

of modern theatrical cinema.” The film would also receive the cover of Cinema Scope magazine and numerous conferences

and lectures on it at Society for Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS) and Visual

Evidence. It marked something new and exciting for cinema.

This immersive documentary on a fishing ship in New Bedford,

Massachusetts stands out for being the cutting edge of the radical emerging style

of the SEL movement and its content and form display certain tenets of ANT. MacDonald wrote,

“these films exemplify the commitment of the SEL to a sense of culture as

continuous transformation, interpenetration, and imbrication.” Latour’s theory of a sociology

of associations, of circulation and movements, the animating of non-human

actors, like marine life or a fishing ship, found in Leviathan is a compelling illustration.

Paravel even, in an interesting anecdote on the French

radio-show Hors-champs, spoke to

Laure Adler about a unique Skype conversation that she had with Latour. During

it he gave her a tour of his apartment room through his computer, as an

illustration of some of his ideas. One could even detect certain parallels

between this gesture and that of Leviathan’s

with its digital cameras that are always in motion and how the film evokes the

fascination of the sensory world.

Another example of Latour publicly supporting a filmmaker

was in January 2010 at the Centre Pompidou where Latour gave a series of

conferences titled Selon/Salon Bruno Latour. There Latour met with other philosophers

and artists to discuss eloquence and demonstration and how they come together

through articulation and composition. In the description of the series, Latour

highlights the oratory arts and how they allow for movement and a liberating potential.

The arts are a form of articulation and they relate to knowledge and science.

Latour wrote, “Each intellectual discipline learns how to articulate the world

in its unique method, to multiply its knowledge, to differentiate itself from

other disciplines, and, to facilitate its expressions and representations.”

This articulation leads to a need for composition and to understand how to

group its varying elements. The archaeologies of these conferences on the

social sciences, philosophy and the arts share a more subjective empiricism. Among

the conferences the early Einstein-Bergson debate was recreated; Latour, Donna

Haraway and Isabelle Stengers spoke on the potential of cyborgs; and surprisingly

the filmmaker Eugène Green discussed the Baroque and L'âge de l'éloquence.

Latour in his introduction spoke about how Eugène Green inspires him. The focus of the conference is on the eloquence of Green’s dialogue most notably in his theater work, but also in his novels and films. Green’s method, he claims, has its roots in the Baroque period, between the Renaissance and an emerging Rational Age, at the intersection of science and religion. Latour wrote,

Latour in his introduction spoke about how Eugène Green inspires him. The focus of the conference is on the eloquence of Green’s dialogue most notably in his theater work, but also in his novels and films. Green’s method, he claims, has its roots in the Baroque period, between the Renaissance and an emerging Rational Age, at the intersection of science and religion. Latour wrote,

Through his Theatre of Sapience, founded in 1977, the

metteur en scène Eugène Green already was searching to revive an art of the

baroque theater through utilizing his declaratory means and proper visuals: pronunciation,

accentuation, rhythm, frontal acting, candle lighting, and gestures: Everything

was codified by very specific rules. Today as a director and writer, Eugène

Green develops in his books and in his films, with the most recent one being La Religieuse portugaise (2009), a new

reflection on eloquence and the incarnation of the parole. How to re-find parole

by a return to the artifice of the elocution, framing and eloquence?

How to bring together rhetoric and demonstration, Latour

asks? These two concepts, which are major preoccupations for Latour, are

elaborated by Green through the importance of dialogue and cinematography in

his work. This interest in language parallels that of Latour’s in his emphasis

on descriptive language for ANT studies. One of the topics that Green brings up

comes from his 2009 book Poétique du

cinématographe. In it he distinguishes between ‘bougants’ (‘move-ies’) and ‘Cinématographe’. This division into two

categories parallels that of Latour’s division between a sociology of the

social and that of a sociology of associations. For Green ‘bougants’ represent

the commercial, non-artistic movies and the ‘cinématographe’ its more artistic

and spiritual potential. Green elaborates in regards to how he films objects,

people, geography and architecture which, he posits, allows for their material

self to truly emerge. This parallels some of Latour’s concepts of how non-human

objects can also have agency.

The Tarde Durkheim Debate

Another

example of how Latour intersects with cinema is his role in the recreation of

the important social theory debate between Garbriel Tarde and Emile Durkheim.

This reenactment of the 1903 debate has Latour in the role of Gabriel Tarde,

Bruno Karsenti as Emile Durkheim and Dominique Reynié as the Dean. It was

filmed in Paris in 2007 in a conference room, filled with an audience, with its

vintage stage by Frédérique Ait-Touatti, research by Eduardo Vargas and recording

by Martin Pavlov.

The film illustrates the importance of their theories for

Latour and a potential interest in the medium. Émile Durkheim, one of the

founders of a scientific sociology, aimed at defining generalizable social

facts like, for example, through statistics the general suicide rates in a

particular Catholic community. Gabriel Tarde, on the other hand, argued for an

emphasis on the microanalysis of actors and networks as, “every thing is a

society and that all things are societies.” Latour prefers Tarde’s theory of

associations and through this recreation aims to recall and call into question

one of the problems with the social sciences.

It is an interesting film as the actors are not necessarily aiming

for physical or oratory verisimilitude, and the debate itself has been

reconstituted (the original whole is no longer available), but what stands out

are the competitive ideologies of the participants, the rationale behind their

ideas, and the confrontation between the hardened ‘scientific’ reason and a

more abstract ‘subjective’ empiricism. The difference is that of a broad

understanding of how society functions through generalizable facts, against

that of an attempt to find the truth-value of a situation by a close analysis

of the actors within a particular site. Through Latour’s identification with

Tarde he is aligning himself with an undervalued tradition in the social

sciences. The underlying gesture is to not pass over this monumental event, but

to better listen to Tarde as his ideas are revelatory and effective ways to

analyze society.

This gesture for a philosopher to recreate an important

theoretical work has a precursor with Michel Foucault who participated in the

recreation of the facsimile document of Moi,

Pierre Rivière, ayant égorgé ma mère, ma sœur et mon frère (1976) by René

Allio. Where Latour’s writing on the Tarde-Durkheim debate can appear to be too

historical (why is this relevant today?), through its current re-creation the

historical event is brought to life and is given new relevance. The debate also

demonstrates Latour’s eloquence, as per his discussion with Green, and turns Latour

into a cinematic screen persona. With his recognizable long face and stern

expression, big black glasses, sharp suit and tie; he is giving his body to

cinema as a visual expression for his ideas. The Tarde Durkheim Debate (1903/2008) is a fitting cinematic

memorial to Latour’s importance.

Latour’s Art Writing and Paris:

Invisible City

Some

of Latour’s art and cultural writing offers interesting ways to bring his ideas

to cinema. In Latour’s essay, Some

Experiments in Art and Politics he discusses Tomas Saraceno’s Galaxies Forming along Filaments, Like

Droplets along the strands of a Spider’s Web (2008) which he sees as a

metaphor for social theory. The work, which was on display at the 2009 Venice

Biennale, creates through organized wires an infrastructure similar to how

Latour conceptualizes ‘networks’. Latour wrote,

What Saraceno’s work of art and engineering reveals is that

multiplying the connections and assembling them closely enough will shift

slowly from a network (which you can see through) to a sphere (difficult to see

through). Beautifully simple and terribly efficient… Namely of explicating the

material and artificial conditions for existence.

For Latour, this artwork offers a great amount of freedom for

understanding connections as a thought experiment. Latour further elaborates on

his artistic sensibility in the exhibition catalog essay From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik, or How to Make Things Public,

where he addresses the need to think of the political beyond necessarily human

and temporal categories to look at people in relation to objects to create a

cohabitation between the two. There are a plethora of artworks, photography and

installations from this Making Things

Public exhibition at the ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe that

attempt to illustrate this aesthetic.

Another good example

of Latour’s engagement with artistic practices is his digital media online

project, Paris: Invisible City, which

is described as a ‘Sociological Web Opera’.

It was first launched in 2004 as part of the Airs de Paris exhibition at

the Centre Pompidou. In Reassembling the

Social Latour wrote, “This somewhat austere book can be read in parallel

with the much lighter… Paris ville

invisible, which tries to cover much of the same ground through a

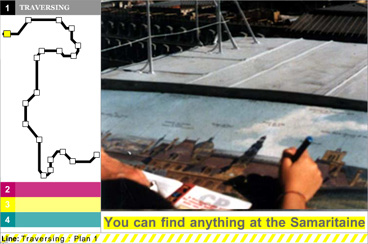

succession of photographic essays.” There are four stages to this tour: Traversing,

Proportioning, Distribution and Allowing. It begins at a department store on

its rooftop panorama of Paris. Through this limited view Latour theorizes that

there cannot be only one Paris (e.g. a bird’s eye view of the city, does not do

justice to its local specificities or how it’s actually operated) but through

many isolated representations of it, there can be a better understanding of it

as a multiple, invisible (Latour’s word, referencing Italo Calvino) and virtual

city.

Anne Friedberg’s conception of the virtual window is useful in

relation Latour’s Paris: Invisible City.

Friedberg description of the screen is that of both a surface and a frame. The

screen becomes a reflective plane onto which an image is cast and the frame limits

its view. This idea relates Paris:

Invisible City towards the cinematic as, building upon Henri Bergson and Gilles

Deleuze, Friedberg argues that computer screens in general have replaced previous

incarnations of screens, from the architectural window to the cinema screen, and

their specificity is the virtual quality of their representational images. Friedberg

wrote,

The term ‘virtual’ serves to distinguish between any

representation or appearance (whether optically, technologically, or

artisanally produced) that appears “functionally or effectively but not formally’ of the same

materiality as what it represents… Virtual images have a materiality and a

reality but of a different kind, a second-order materiality, liminally

immaterial.

The world that Latour recreated with Paris: Invisible City depends on the computer screen in a novel way,

which reflects Friedberg’s conception of the virtual screen, as it finds new

ways to describe a society and in its own way tell a story.

ANT and Film Analysis

ANT as a model to analyze films has its benefits and

drawbacks. Where it is probably correct to assume that Paravel had been

influenced by Latour’s conception of ANT it is more difficult to broadly use it

as a tool to analyze documentaries. Though one possibility would be to look at

certain documentaries and then make a general taxonomy of how they animate some

of ANT’s major tenets. But this can be limiting as well as in then how to

interpret these scenes and their meaning? There are a few documentaries such as

Silvered Water, Syrian Self-Portrait (2014),

The Iron Ministry (2014) and 88:88 (2015) which are worth exploring

as case studies for ANT’s usefulness for film analysis and to illustrate its

potential.

Wiam Simav Bedirxan and Ossama Mohammed’s Silvered Water, Syrian Self-Portrait is a

documentary on the atrocities of the Syrian civil war. It is a hybrid film made

from the directors’ personal footage and found footage from the Internet of the

atrocities plaguing Syria. The military regime that rules the country does not

allow for filming (if caught filming the person is typically killed) and the

violence of Silvered Water’s imagery is

typically is not reproduced in Western reporting on Syria. In the documentary there

is a scene of the ruins of an old building where a broken outdoor faucet is

dripping. It is a lengthy scene as Bedirxan decides to focus on this one

mundane activity. This broken faucet can take on what ANT describes as the

agency of a non-human actor. ANT wants to distribute agency as broadly as

possible. The social and historical trajectories of the country with its recent

military violence take the specific form of this faucet as an actor in this

scene. Even though the city is being destroyed there is still this

micro-activity occurring. But the problematic aspect of focusing on this scene,

solely to compare it to ANT, would be to take away from the overall project of

the film with its message of urgency about the violence of the Syrian military on

civilians and the destruction of Homs.

Another example is Isiah Medina’s experimental documentary 88:88. Through its portrait of a working class neighborhood in Winnipeg, Medina captures these interactions between nature, people, and community in a striking and unique way. If ANT posits that everyone and everything is profoundly relational then this experimental form of filming and editing can be seen as heightening the performative nature of these interactions and the networks connecting them. ANT presumes that a person’s identity is not prefigured by the moment of analysis (or filming) so in 88:88 brief shots of figures and lack of psychology have condensed the actants in enacting their relationships. These parallels offer some insight but perhaps a more helpful reference in understanding Medina’s film would be to compare it with works that it is most likely directly citing, such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010) and Adieu au langage (2014) or other diary and structural films.

Another example is Isiah Medina’s experimental documentary 88:88. Through its portrait of a working class neighborhood in Winnipeg, Medina captures these interactions between nature, people, and community in a striking and unique way. If ANT posits that everyone and everything is profoundly relational then this experimental form of filming and editing can be seen as heightening the performative nature of these interactions and the networks connecting them. ANT presumes that a person’s identity is not prefigured by the moment of analysis (or filming) so in 88:88 brief shots of figures and lack of psychology have condensed the actants in enacting their relationships. These parallels offer some insight but perhaps a more helpful reference in understanding Medina’s film would be to compare it with works that it is most likely directly citing, such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010) and Adieu au langage (2014) or other diary and structural films.

The same would apply to J.P. Sniadecki’s The Iron Ministry. Similar to the SEL Leviathan, The Iron Ministry is a

condensed trip through the major Chinese rail-road system. It offers a

fascinating glimpse to its busy activity, myriad of passengers and interviews. In

one scene the camera is recording a young child criticizing American ideology late

at night on the train. This scene recalls Latour’s focus on description without

interpretation. But then what? The fact that parallels can be drawn between ANT

and certain filming techniques used in specific documentaries does not confirm

that it is necessarily a useful tool for the analysis of film. More research on

the subject is still necessary.

ANT, Documentary and Media

There has also been scholarship on ANT and its relation to

media and documentary which gives a better understanding of how other scholars

have imagined this relationship. Here are two examples of scholarship on ANT’s

relation to media and documentary: Ilana Gershon and Joshua Malitsky’s essay Actor-Network theory and documentary studies which discuss how

science studies and ANT can inform documentary scholarship; and Nick Couldry’s Actor Network Theory and Media: Do They

Connect And On What Terms? which elaborates on ANT’s relation to media in

general. These two essays offer interesting methodologies on the subject.

Gershon and Malitsky’s essay is perhaps the better of the

two to bring ANT to the analysis of documentary and its para-textual objects.

Instead of asking how the film animates certain ANT tenets they attempt to use ANT

to discuss the larger narratives surrounding the films, the films’ possible

truth claims, and the broader social response to them. Gershon and Malitsky are

reacting to the post-modernist critiques of ‘claiming the real’ and its recognition

that truths are socially constructed. Instead they are claiming a similarity

between ANT’s distrust of dichotomies in scientific practice to that of how

documentaries construct truths. For this they propose to study the extra-textual

information around the film as a method to interrogate its own truth claims.

Gershon and Malitsky, cite John Law, who “delineates how ANT

is fundamentally a theory of relationality, the analytical task of figuring how

these relationships condense in various people and objects.” ANT allows for

techniques to reveal how truths are socially constructed and how interactions

are transformed into representations. Gershon and Malitsky propose four

conceptual consequences in bringing ANT to documentary: everyone and everything

contributes to how interactions take place; not all actants are the same; ANT

insists on the performative nature of relations and their forms; and actants

are all network effects. This would lead to,

The ANT perspective makes the

circulation of putative truth a question of how different actants contribute to

shaping a network through specific interactions. What ANT scholars provide are

techniques for sidestepping the ontological question of truth entirely and

focusing instead on truth-value. In other words, what the ANT perspective

offers are techniques for understanding how representations might be

transformed into facts through the labour of specific networks.

For documentary the ANT perspective would involve bringing

all the aspects of the documentary from production, distribution and reception

to see how the documentaries themselves are actants, which each convey their

own information. This would make the study of them more reflexive as analytical

moves provide ways to think about how truths and facts are constructed. For Gershon

and Malitsky, “That is, ANT provides a way of imagining documentary

pre-production, production, post-production, distribution and exhibition

practices as an integrated network for circulating knowledge.”

In his essay Actor

Network theory and Media: Do They Connect and on what Terms? Nick Couldry describes

ANT as an attempt to explain the social order. Couldry elaborates,

through the networks of connections between human agents,

technologies and objects. Entities (whether human or non-human) within these

networks acquire power through the number, extensiveness and stability of the

connections routed through them, and through nothing else.

Couldry uses ANT to generate a

theory of connectivity that brings together the social and nature, which

includes the potential of media. Within these relations, it is the networks

that set the agents in positions relative to other agents. Building on Roger

Silverstone, Couldry argues that,

Networks (and therefore ANT)

tells us something important about the embeddedness of social life in media and

communications technologies, but they do not offer the basis for a completely

new theorization of social order, nor even a new way of analyzing social

action, in spite of claiming to do just that.

ANT is interested in humans and

their entanglement with technology. Couldry argues that “ANT’s insistence on

the necessary hybridity of what we

call ‘social relations’ remains a valuable antidote to the self-effacing,

naturalizing potential of media discourse and of much discourse in media

studies.” Couldry citing Tarde elaborates on the increasing simultaneous conversations

spread over a vast geography as one of the major important developments, which

has grown exponentially since Tarde was discussing newspapers. Couldry instead

of seeing technology, media or even the Internet as a faceless mechanical

entity prefers ANT for being able to localize the specific relations entangled

within it.

But Couldry also sees a limit to ANT and has his own

critiques of it: ANT has a problematic relation to time since it neglects it. Couldry

sees in this neglect of the long-term consequences of networks as overlooking

of social power and the possibilities of resistance. He does not view ANT as

successful when analyzing texts that are meant to be interpretative. As well

Couldry argues that ANT has little to say about the processes that come after the establishment of networks.

Althought Couldry sees a

relationship between ANT and media theory, he argues that it is both

significant and uneasy. It is an antidote to the more functionalist versions of

media theory but its problems of an insufficient attention to questions of

time, power and interpretation are still serious. But it is a good base for more

research around these questions.

Conclusion

Bruno

Latour, even without directly being involved in film studies, has still managed

to put pressure on the cinematic in interesting ways throughout his career. This

influence is seen through his teaching relationship with Véréna Paravel, who

would bring many of ANT’s tenets to the radical approach of the ethnographic documentary

Leviathan, and also through his

participation in the recreation The Tarde

Durkheim Debate, which has him casted as Garbriel Tarde to eloquently

debate some of the social theory ideas that contributed to shape him. His art writing,

curation, and creations like the virtual Paris:

Invisible City have theorized some key concepts in the aesthetics that he

would privilege, which would enact his social theories by bringing together

objects and humans with the goal of creating new relations. And finally

actor-network theory allows for an interesting new approach to study the documentary,

which still needs to be further developed. Latour’s intellectual work has

provided cinema and film studies with many stimulants and his ideas still need

to be further explored for a better understanding of what they have to offer.

No comments:

Post a Comment