Some quotations from A Third Face where Sam Fuller discusses John Ford. – D.D.

***

“Thanks to Herbert Brenon

and his patronage, I met members of the “old school” – veteran directors like

John Ford, Raoul Wlash, Howard Waks, Leo McCarey, Todd Browning, Frank Borzage

– the guys who created Hollywood out of a bunch of fruit orchards and dusty

lots with a burning desire to tell great stories.”

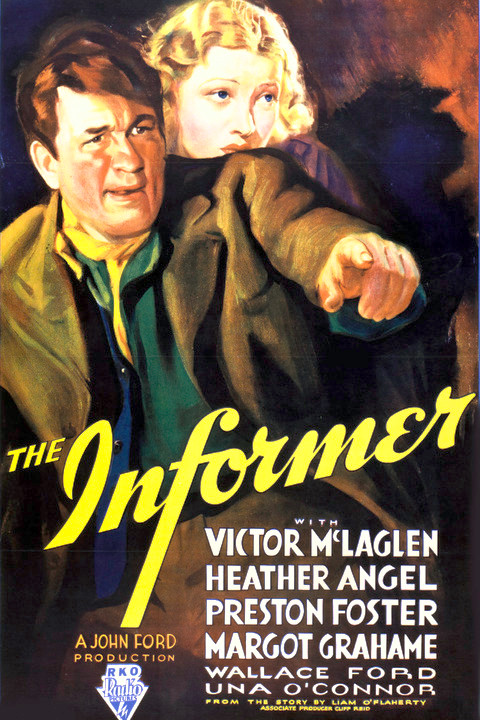

“My favorite film of those

formative years was The Informer

(1935) by John Ford. It is truly a masterpiece. Of all the wonderful directors

I met in Hollywood before World War II, I paid special attention to John Ford.

John had a vision up on the screen. John was very supportive of me in the early

years when I needed it. He became a friend and a mentor. Ford invited me onto

his sets, and, when I started directing, he’d drop in on mine. I cherished the

times we were together.

Some critics, looking for a

catchy tag line, have called me “the Jewish John Ford.” It was a ridiculous

thing to say, though I understand people needing reference points. But let’s

face it, next to the monumental Ford, I’d always be a neophyte. To understand

the scope of John’s career, you have to remember that he began as an actor way

before the talkies, with a small role in Birth

of a Nation, in 1915. Over the next sixty-odd years, John Ford would direct

about 140 films. John was a giant, having done it all in Hollywood. I learned a

helluva lot of stuff from Ford, but one of the most important lessons was

modesty. Ford was the most self-effacing of guys. When asked what brought him

to Hollywood, he replied, “The train.”

Because he wanted complete

artistic control, Ford started producing his own pictures. The desire to shape

every aspect of his movies resulted in some of his finest work: She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Rio Grande (1950), The Quiet Man (1952), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence

(1962). His mastery of the entire process was always an inspiration for me.

I’ve never tried to imitate his work – nor anyone’s, for that matter – but to

be mentioned in the same breath as the great Ford will always be a profound

compliment. I remained close to him until his death, in 1973. For me, John Ford

was everything I loved and respected about Hollywood.

“Each society has its own

way of taming young people so they won’t destroy themselves and can mature into

useful citizens. By focusing on bad boys, I wanted to thank my mentors for

helping me stay on the high road. I was lucky. At critical moments in my life, role

models like Arthur Brisbane, Gene Fowler, Terry Allen, George Taylor, Herbert

Brenon, and John Ford took me under their wings and kept me from derailing,

showing me how to be a mensch.

“My statuesque stripper,

Cathy, needed beauty, sex appeal, and intelligence. I picked Constance Towers

because se had all three, in spades. John Ford had introduced me to Constance.

She’d appeared in Ford’s Horse Solders

(1959) and Sergeant Rutledge (1960).

A trooper all the way, Constance became a good friend.

“We shot Shock Corridor in

about ten days. Once, John Ford stopped in for a surprise visit. It was a

tremendous morale booster.

“Sammy, why’re you shooting on this

two-bit set?” he asked.

“No Major would touch my yarn, Jack,” I

said. “It’s warped. It’s about America.”

“You’re going to stir things up again,

like Steel Helmet.”

“Maybe. I’ve just got to do this movie.”

I strolled with Ford down the long, white

corridor, both of us puffing cigars. Something jarred his memory.

“Here was the church,” he said, pointing.

“There was my set for the prostitute. Woy over there was the IRA

interrogation.”

Was it possible that he’d shot one of his

greatest movies, The Informer, on

the same miserable soundstage? Yes, he explained, back in 1935 RKO was upset

about his plans for a pictured based on a Liam O’Flaherty’s proletarian novel

about the Irish Republican Party rising against the British. They gave him an

embarrassingly small budget, forcing him to rent that very space to shoot the

picture. I was stupefied that the great John Ford had been treated

disparagingly. He read my face.

“Me too,” he said. “I had to make that

movie.”

“A young director named Bertrand

Fèvre asked me to play a part in Bleeding

Star, his debut short film. Télérama, a widely read TV magazine, hired me

to write a children’s book entitled Pecos

Bill and the Soho Kid, a Western based on an idea I’d had for a TV show.

Like the treatment for the show, the book featured an adult who’d never grown

up and a kid with a Cockney accent and mature beyond his years, who took

imaginary trips together, catching clouds with lassos. Illustrated by Belgian

artist Frank le Gall, my little book was dedicated to John Ford. I was thrilled

when my publisher received hundreds of enthusiastic letters from young French

readers.

No comments:

Post a Comment