Consumed by David Cronenberg (Hamish Hamilton, 2014)

“I’m

a very sick woman. Does that turn you on?” Dunja, a Slovenian woman at the

Molnár clinic in Budapest, asks the New York journalist Nathan Math. “Well, I told you. I’m a failed medical

student. Now I’m a medical journalist. So, yes, I guess sickness does turn me

on in a way.” (Pg. 30). A sick woman, who is about to get an illegal

radioactive treatment for her breast cancer, tries to seduce a medical

journalist, and they end up having sex. She transmits to him a rare STD, the

Roiphes disease, which he ends up also passing to the women that he’s seeing,

Naomi Seberg. Naomi, also in the field, is researching to write a book on the

case of Aristide Arosteguy, a famous philosophy professor, who left his native

France for Japan, after being investigated for cannibalism, eating his wife

Célestine. The title of the book comes from Barry Roiphes, the now-retired

doctor famous for discovering the disease, who wants collaborate with Nathan to

tell his life story, work history, and his experiments on his daughter, Chase,

who is now dealing with some mysterious form of post-traumatic stress.

Surrounding all

of this is the ghost of the Simone de Beauvoir-like Célestine, who’s never

encountered because she was supposedly eaten (the description of the

photographic death scene is nightmarish), but who prior was sexually

promiscuous with her disciples, who Naomi is now interviewing. Célestine and

Aristide describe themselves as open to ‘philosospams’, episodes of obsessive

behavior involving sexual affairs or political activity. After the two

professors attend the Cannes film festival as a jury members, Célestine becomes

obsessed with a controversial North Korean film, The Judicious Use of Insects, which she suspects her former lover

Romme Vertegaal made under a pseudonym, specifically for her. This experience

causes in her a rare form of apotemnophilia, and she starts to believe her left

breast is infected with bugs and would stop at nothing to get it removed. (The

diagnosis scene appears in a slightly altered form in the EYE Film Institute

commissioned Cronenberg video, The Nest

starring the raw Evelyne Brochu).

What is it

about episodes like these – typical of Consumed

in their mixture of Eros and Thanatos – that draws people towards the

works of David Cronenberg? Sex, disease and death. Journalism, cameras, and

social media. This is the shadow world of Consumed.

It’s these taboo themes and obsessions, which are typically repressed in

everyday life, that are brought out into the open and freely indulged. In

Cronenberg’s world, more general human experiences like relationships,

education, professions, growing old, diseases and death are heightened towards

an extreme, parasitical level.

This theme of

the parasitic and infections is everywhere in Consumed. Nothing is safe from it. If something bad could happen,

then it will. No wonder Stephen King praises the book. But there is almost a

mathematical and scientific structure to how it unfolds, just like in a

Cronenberg films. After Cronenberg’s more recent gangster films (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises)

and probing the subconscious (A Dangerous

Method), now he’s returning to the original body horror of his early career,

but the world is different and its implications scarier. So similarly to Maps to the Stars, Cronenberg’s most

romantic film in the Goethien sense, or Cosmopolis,

in Consumed and in these recent

works, the worlds, both individual and social, end up falling apart. For

example, Agatha is scarred with burn wounds (among her other psychological and

physical problems), Eric Packer has an asymmetrical prostate, and in Consumed bodily mutations and deviations

are rampant. But even if the world is dark, there is still a beauty to this

gesture of showing it fall apart and disintegrate in its multifaceted forms.

There are many

episodes from Consumed that bring to

mind ones from other Cronenber films. The journalist protagonists and their

globetrotting adventure recalls Naked

Lunch, the medical setting and the procedures that go awry makes one think

of Dead Ringers, the carnal love

affair that takes place in Asia is reminiscent of M. Butterfly, and the mad scientist character could be right out of

The Fly.

Cronenberg had

always wanted to write. Originally, after his first two underground films (Stereo, Crimes of the Future) he moved

to Tourrettes-Sur-Loup, France to try to become a novelist. But he would return

to filmmaking, as he tells Serge Grünberg, because it was “a ‘modern’ way of

writing.” And with his filmmaking practice he would remain loyal to writing:

creating his own stories, writing his own screenplays, and adapting novels. And

in this period he would have close working relationships with many esteemed novelist

including King, William S. Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, and Don DeLillo.

It’s

worth noting Cronenberg’s popularity and relevance. Where other older directors

like Peter Bogdanovich or John Sayles can no fund their films and start taking

up other projects like film blogging or novel-writing, with Cronenberg there

isn’t the sense that he ‘lost it’ with the mass public. In the ten years since

the president of the publishing house Hamish Hamilton, Nicole Winstanley, asked

him if he wanted to write a book, throughout his sixties he was able to

artistically reinvent himself, working with some of the most famous young

stars, Robert Pattinson and Mia Wasikowska, on the two critical successes Cosmopolis and Maps to the Stars.

So the next

question: is David Cronenberg a good novelist? Yes. With Consumed, at a length of 284 pages, he crafted a gripping

page-turner, which isn’t clumsy in its prose, and in it he creates both a world

distinct to itself, and one that is in parallel to his body of work as a

filmmaker. Though let me said, if it wasn’t written by him it would probably

have received a lot less attention. But Cronenberg is still great at creating

interesting characters, atmosphere, dialogue, and intrigue. There are two

parallel stories that take place and the switching between them is never

awkward. Though there is a section where Aristide is describing what has

happened to Célestine, which goes on for too long at 50 pages, and lacks the

multi-character energy of the rest of the book.

The Nabokov

influence, which Cronenberg speaks of, is there, as they are both cerebral

writers that regularly bring up major ideas of continental philosophy and

psychoanalysis, along with a wider openness towards the arts and culture.

Cronenberg is especially fond of describing cameras and lenses, though maybe too much.

Naomi is as

complex and fascinating as Maxine Tarnow from Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge, both young women

investigators. And there are also similarities between Consumed with the world of Infinite

Jest, as in both works the authors critique the growing use of technology

to mediate interpersonal relations, and the role of entertainment in our

culture and its ability to become a gross obsession. As well Dr. Roiphes’

project seems similar to James Incandenza’s, and Consumed bleak and ambiguous cliffhanger ending also recalls David

Foster Wallace’s.

On a potential

adaptation of Consumed, Cronenberg

has said: “I’ll let David Fincher or Neil Jordan destroy my novel.” And he

presently does not have any new projects in the works.

***

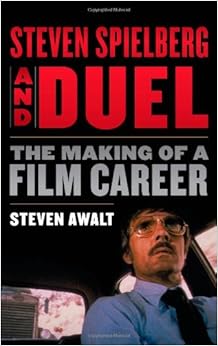

Steven Awalt's

new book, Steven Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film Career, is about a little-known period in the

director’s career. For an older generation, the film might be known for its

acclaimed television screenings, for a younger one it might not be that

familiar as Spielberg is now more associated with his classics like Jaws, the Indiana Jones films or

Jurassic Park. What is it about Spielberg’s early career that demands

re-evaluation? Even the author of Steven Spielberg and Duel doesn’t deny

that the film is “a somewhat forgotten work.” But according to Spielberg himself, Duel is “the key to unlock a career for me.” So with that, the book’s aims are two-fold:

it explores Spielberg’s early television career at Universal, and it tells the

equally gripping narrative of the film’s production.

While Spielberg’s early career is usually treated cursorily,

in Steven Spielberg and

Duel Awalt does it justice by making it the subject of his book.

Awalt, who is a scholar on this period in Spielberg’s career, focuses on

Universal’s television production and Duel’s

many collaborators that would lead to make the film a reality through its

different stages of production. The television dramas that Spielberg worked on,

and which are discussed in depth, include his episode Eyes starring Joan Crawford for Night Gallery, LA 2017 for Name of the Game,

and Murder by the Book for Columbo. In this period the economic

restrictions of the productions instilled in Spielberg a quick working

practice. Spielberg was working with a lot of older technicians, many from the

classical studio era (and was sometimes in conflict with them), which led to a

rich collaborative atmosphere. The many collaborators of Duel include its lead actor Dennis Weaver (Spielberg was a big fan

of his performance in Touch of Evil),

author and screenwriter Richard Matheson (whose screenplay is included in the

book), director of photography Jack Marta, stunt coordinator Carey Loftin (Bullitt), editor Frank Morriss, composer

Billy Goldenberg, producer George Eckstein, and studio executive Sid Sheinberg.

This

impressive group led to a creative atmosphere that gave Spielberg the

creative freedom to make Duel especially cinematic. It’s practically a

non-verbal sensorial experience as its story is told through ambitious

filmmaking techniques more so than the conventional ones associated with the

television of this period, which includes impressive mobile shots following the

car, a long-take into a café, and dramatic staging during the confrontations.

The origins of Duel begin with Richard Matheson who was

inspired to write the original short story after a similar experience happened

to him. The murderous truck of Duel,

which pursues David throughout the film, is a significant villain for multiple

reasons. First off, he is significant as a faceless antagonist, which is the

catalyst for the film’s Hitchcockian wrong man narrative. Secondly, the

chase story would become a regular structural trademark for Spielberg. And

thirdly, as a symbol of an environmental problem, as its petrol freight

reflects a natural resource that is constantly and recklessly exploited under

industrial capitalism.

Also related is Duel’s critique of patriarchy. The film begins

with a travelling salesman named David Mann driving down a desert highway. He

is listening to the radio where on a talk-show a caller is discussing a survey

where he admits that he’s no longer “the head of the family.” Shortly after the

driver stops at a roadside Laundromat to call his wife in which they continue

their argument from the previous night. Like the son Michael Brody from Jaws

who can’t connect with his father, or Roy Neary in Close Encounters of the

Third Kind who runs off from his family, or lonely Elliott in E.T.;

Spielberg is presenting the disintegration of the nuclear family. And as he

expands upon in his Suburban trilogy (Close Encounters, E.T., Poltergeist),

Spielberg in this early stage of his career is chronicling issues surrounding

Fordism and the growing class of American society and especially the complexity

of their emotional lives.

In the book,

Awalt engages with the discourse around Duel

by employing a close reading of every scene in the film. Awalt is especially

critical of Andrew M. Gordon’s contentious psychoanalytic reading of the film.

The side-bars and footnotes in the book offer a wealth of supplementary

information regarding the film. There are side-bars that focus on the swearing

that had to be censored, harbingers, its class consciousness, and

how some of its footage

would be used in an episode of Hulk

(to Spielberg’s chagrin). Awalt debunks the myth of a young Spielberg escaping

the Universal Bus Tour and setting up shop, as the truth is that his father

knew a librarian that sponsored him as an intern. And there is a fascinating

footnote of Spielberg’s rare cameos in his own films.

In terms of

Spielberg making-ofs, Awalt’s book isn’t as richly illustrated and colorful as

some of the other ones (The Complete

Making of Indiana Jones, Memories from Martha's Vineyard). But it’s as

gripping and informative as either Carl Gottlieb’s The Jaws Log or any of Laurent Bouzereau’s special features. There is a charm to the modesty of the

project, in comparison to more theoretical film books, and Awalt’s sense of story-telling

is open, fun and generous. For

example, if in Ray Morton’s book on the making-of Close Encounters of the

Third Kind he makes the argument that it’s Spielberg’s first personal film

because it owed to his earlier teenage film Firelight. (Spielberg

himself typically identifies his first personal film as E.T.). Awalt

pushes this intertextuality even further by arguing that Duel owes to

Spielberg’s earlier train-crash home movies that he’s famous for bringing up.

It’s the casualness and insight of observations like these that reflect a deep

knowledge and contemplation of Spielberg’s cinema, which makes Awalt’s analysis

so pleasurable to read.

Steven

Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film Career stands alongside the other note-worthy

recent Spielberg books that includes: James Kendrick's reconsideration of

Spielberg’s oeuvre which argues for the persistence of his pessimistic themes

and the complexities of its ideological incoherence (Darkness in the Bliss-Out), Richard Schickel's general overview and

interview with the director (Spielberg: A

Retrospective), and the official book on Schindler's List and the USC Shoah Foundation.

No comments:

Post a Comment