“There’s a scene I would

like to have in a film. About an elderly and prominent man. A young man comes

to see him, to get something from him, to learn how achieve prominence and

success. The old man is facing him this young man – virile, healthy, ambitious.

All the old man tells him is ‘Play golf. Sleep eight hours a night. Do not

smoke. Do not eat too much. Be sure not to put on weight.” - François Truffaut

The new book François Truffaut: from The New Yorker,

1960-1976 published by The Film Desk consist of five short featured

interviews with the French director, and as the title indicates, they start in 1960

when he’s at the start of his filmmaking career all the way to 1976. Lillian Ross,

who is best known for her book Picture

on the making of John Huston’s The Red

Badge of Courage, writes in the signature The New Yorker cosmopolitan writing style, which is attuned to larger

cultural descriptions such as close details to diets, appearances, fashion, and

social life just as much it does to art. These interviews make a nice counter-point

to Antoine de Baecque and Serge Toubiana’s exhaustive biography and to the

excited interviewer in the Hitchcock book – Truffaut’s criticism is too

literary and polemic to reflect the casual generosity of these other texts or

his rare media appearances.

On the Hitchcock

interviews,

“From the third day on, his sensitivity emerged. He became self-critical. He described scenes in which he thought he had done something that was foolish or pretentious or careless. I was struck by the contrast between the public man, so sure of himself, so cynical, and what seemed to me to be a very vulnerable man, very emotional… And I learned what I needed to know… the principle, extremely important, that an emotion must be created on screen and then must be sustained – on the technical level as well as on the scenario level.”

Truffaut becomes

just as open in these interviews with Ross. Some of Truffaut’s fascinating

comments include: Morris Engel’s Little

Fugitive is quoted as being a big influence on the New Wave for teaching

them about the benefits of smaller, more independent productions. There are

interesting remarks on his youth and childhood in general. The five films about

childhood that Truffaut admires the most are Zéro de conduite by Jean Vigo (“who has had the greatest influence

on my work”), The Road to Life, Germany Year Zero, Little Fugitive, and The Two

of Us. (It’s a shame that he never got around to The Night of the Hunter and Moonfleet,

films that would only be reevaluated after his time). Truffaut

discusses his literary taste: he’s a great admirer of Henri-Pierre Roché, whose

two novels Jules et Jim and Les Deux Anglaises et le continent he

would adapt. Truffaut prefers the American society and their media landscape to

that of the French, even though he acknowledges that it’s from the position of

a visitor (his remarks of the French during the occupation and the post-68

depoliticization are especially scathing). In Paris he prefers snack bars to haute cuisine: he recommends Manny’s Bar

on Rue Washington street. On Close

Encounters of the Third Kind, “Spielberg telephoned him in Paris and told

him he liked the way Truffaut wore an old-fashioned wristwatch and always wore

a necktie.” It almost appears that he learnt English, which he speaks about at

length, to read more film books as the two books he describes as Extraordinaire! (which is quoted

phonetically) are Memo from David O.

Selznick and Vincente Minnelli’s I

Remember It Well both which he procured at the “best shop for film,” Larry

Edmunds Cinema & Theatre Bookshop on Hollywood Boulevard. There is also an

indelible anecdote of Truffaut going to Cinemabilia at 10 West Thirteenth

Street in New York where he scours through their books. On academia, “Their

interest in movies is fine, he thinks, but intellectuality about movies without

enthusiasm may not be such a good thing.” Truffaut is also critical of some of

his projects, and there is surprisingly little talk of Jean-Pierre Léaud or any

of the other New Wave directors.

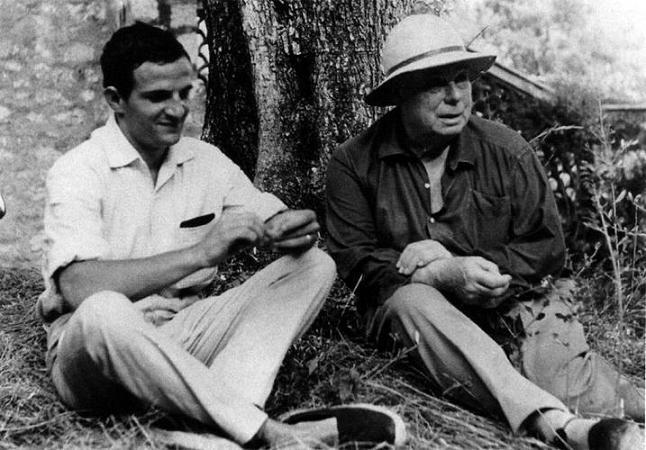

There is almost

a Groundhog Day repetition at the

start of each piece as Ross repeatedly describes Truffaut, his current project that brings

him to town, the magazine’s relationship to him, and how many movies that he’s

seen in his life. From the age of eleven to twenty-eight he’d seen 3000 films

and by the last trip at age of forty-four he would have seen 2450 more, which

adds up to 5450. The life of a cinephile! There is an ambivalence for Truffaut

between this enthusiastic film love with a melancholic solitude. His travels

are described to be lonely and he seems to really cherish his friendships,

especially with Jean Renoir. There is the impression of Truffaut growing older

through the sixteen years of these interviews. He becomes more mature, ages

physically, learns English, and directs more films. It seems like it could be

right out of Domicile Conjugal when

he talks about his two daughters,

“They don’t live with me, because I am divorced, but I see them constantly. And I constantly take them to see movies. Luna is eleven, and I took her with me to see Gone with the Wind. She said, ‘It’s the most beautiful movie I have ever seen.’ Eva is eight. She compelled me to see Mary Poppins twice. Because I saw it through her eyes, I loved it. Most of the time, I wind up liking the same movies they do.”

Knowing that

Truffaut died of cancer too young at the age of 52 shadows the book and

makes casual observations of life, growing old and death even more melancholic. Because of this the small moments of enthusiasm and joy come off as even more important and what makes life worth living. In 1973 Ross describes him as, “He is getting more and more lovable

with age (by the time he’s eighty he’ll probably be a cross between Mr. Chips

and Jean Gabin).” Life is short. Make the most of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment