Jean-Marc Vallée on Friday October 9th for the Festival

du nouveau cinéma held a commented projection of Ishii Katsuhito’s The Taste of Tea. After a 30 minute

delay in starting due technical reasons (the adjuster on both his microphone

and the film weren’t working properly), a huge crowd walked into Cinema 1 at Cinéma

du Parc for what turned out to be a very special night.

But Vallée’s special event was a little uncalled for. Why do

a commentary on someone else’s film, and why at this year’s edition of Festival

du nouveau cinéma? Why this bizarre Japanese film? Is it even a ‘DJ’ set or a

Master class, as he described it? And, more to the point, was it even entirely

successful?

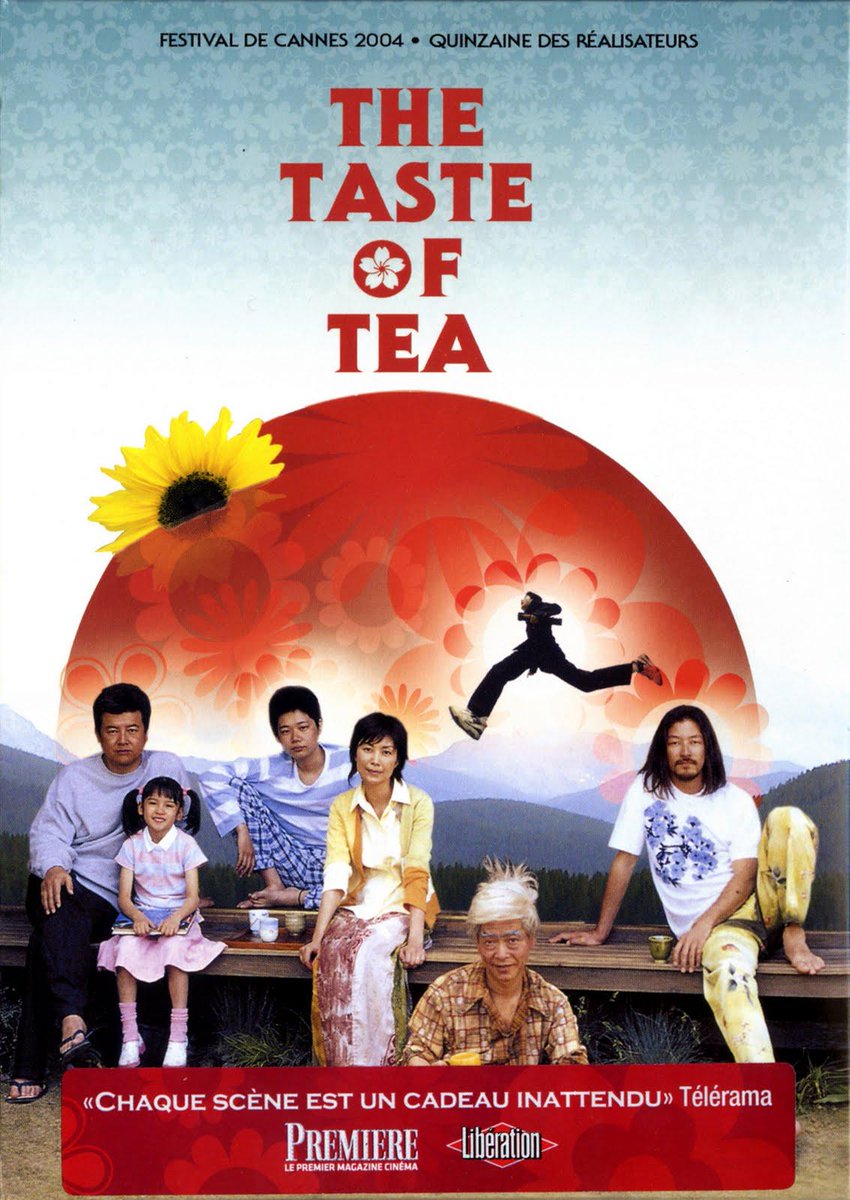

The Taste of Tea…

Tea… Dominique Fortier’s Québécois novel Du

bon usage des étoiles about John Franklin’s 19th century voyage

to North America, which Vallée is planning to adapt, has tea as a major subject

– so could Vallée be preparing, and sharing, some of his inspiration for the

film that he’ll be making in a few years? The answer is: no. The Katsuhito film

has very little, if anything at all, to do with actual tea.

So why do a commented projection? Why right now? And why get

a crowd to wait a lengthy period of time just for the minute details of the

technical equipment to be set up properly and work to his requirements? The

answer: For the beauty of the gesture.

There was no real reason for Vallée to put on this event, except for his desire

to experience the film in a social setting and to share it with his neighbors,

friends and public. This was reason enough to put on the show.

Vallée’s commentary wasn’t too talkative (especially later

on in the film), as he would let the scenes play out (the audience also had to

focus on the French subtitles) before pointing out what he liked about it. But

what he did say had a lot of meaning. For example, Vallée’s comments on Ishii

Katsuhito were almost those of a self-portrait as many of the observations

could also be used to describe himself. Vallée spoke of Ishii Katsuhito as a

director of total liberty and experimentation, and with that, success and

failure.

Vallée said one thing about The Taste of Tea that seems important: how he didn’t think it was

perfect and how he thought some scenes, and the film as a whole, were too long.

Vallée would add, in a humbling modesty, that he didn’t think his own films

were perfect either. But the point was, how these flaws can contribute to the

charm of a film. And through Vallée’s discussion of some of the film’s scenes

and their duration (“I would have cut it here,” “this scene is 10 seconds too

long” etc.), what comes across is a conviction in what’s visually essential to

get to the heart of a scene, which can make a film come alive.

But why choose to do a commentary on The Taste of Tea? The obvious choices would have been Les bons débarras and The Ice Storm, two films that he’s

publicly spoken highly about. Or with his upcoming Janis Joplin film to look at

films around that similar topic and period like Almost Famous or Taking

Woodstock. The answer: So not only is Vallée interested in the beauty of the gesture but also the gesture to surprise.

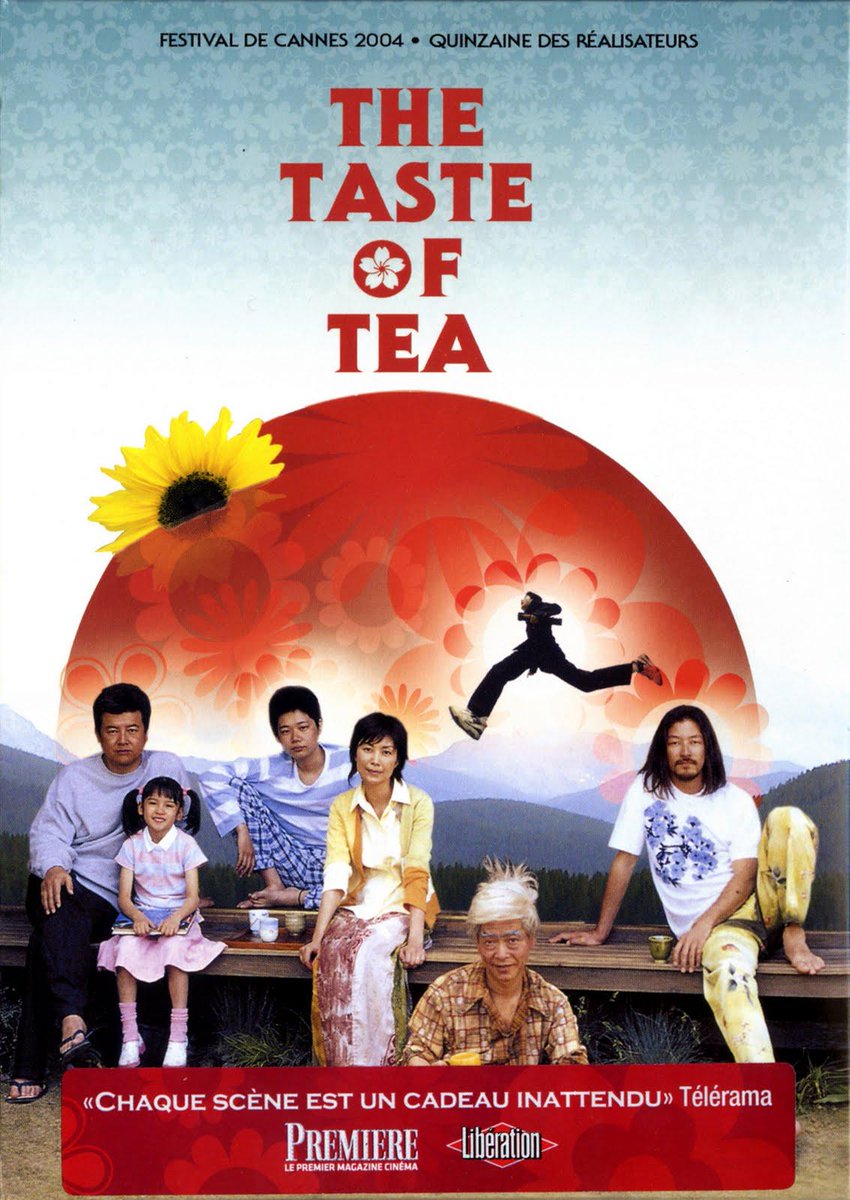

The Taste of Tea,

which premiered at Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 2004, Vallée discovered at

that year’s edition of the Fantasia film festival (around the time of the

production of C.R.A.Z.Y.), and since

then he has seen it over a dozen times. Vallée spoke of even meeting Ishii

Katsuhito who told him about working on the animated fight scenes for Quentin

Tarantino’s Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (it

goes without saying that the animation and drawing scenes in The Taste of Tea are great too).

The connections between The

Taste of Tea and C.R.A.Z.Y. are

worth exploring since there many striking similarities between the two. The

obvious connection is the emphasis on the family and the children and how

through their very specific stories there can be something universal that

emerges. There is also the films’ blend of fantasy and reality which give both

of them their surrealist tone. The two directors also both edit their films in

striking and poetic ways. But perhaps the most Valléeien aspect of The Taste of Tea is the character of

the older brother and grandfather. The older brother in the film is a

music-recording technician (which parallels Vallée’s own sonic perfectionism)

and the grandfather was always testing his tuning fork. There’s even a

psychedelic music video for a song about mountains sung by the parents which

recalls Gervais Beaulieu passionately singing Charles Aznavour songs in C.R.A.Z.Y.

And there’s something Japanese about Vallée’s films in terms

of their spirituality through his emphasis on ghosts, which in Japanese

folklore are called Yūrei. These are wandering ghosts that still need to accept

their situation – this can be seen in Japanese films as diverse as Ugetsu, The Taste of Tea and Journey to the Shore. And in the films

of Vallée through the reappearance after death of Raymond Beaulieu (C.R.A.Z.Y.), Rayon (Dallas Buyers Club), Cheryl Strayed’s

mother Bobbi (Wild), and most

recently Davis Mitchell’s deceased wife (Demolition).

So much that was said throughout the two-and-half hours

contributed to a better understanding of Vallée’s cinema and to Ishii

Katsuhito’s mysterious film. Through this innovative commentary Vallée

continues to explore his contemplation of cinematic images and their potential.

Even though he wasn’t saying much by the end, as it progressed his voice emoted

more as he was being affected by the film. And by the end as he was left only whispering

a few key words, he was able to do it again: to invisibly put himself into a film. It’s one of his best audio

commentaries, up there with the ones on C.R.A.Z.Y.

and Wild (here’s hoping the

rumored Café de Flore commentary one

will one day emerge). Every movie should have a Jean-Marc Vallée

audio-commentary track!