"My friend Joyce Kim took this picture when we were shooting Putty Hill back in 2009. Looking at it now, I can't help but see a gesture symbolic of what many citizens of Baltimore (myself included) are feeling right now. If it's not clear enough, I'll volunteer a caption: FUCK YOU, WE'RE ANGRY." - Matt Porterfield

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Wednesday, April 29, 2015

Canadian Cinema : Summer 2015

We’ve got some

good directors in Canada. To make a short list there’s Jean-Marc Vallée, Guy

Maddin, David Cronenberg, Denis Côté, Sarah Polley, Stéphane Lafleur, Kazik

Radwanski, Igor Drljača, Matt Johnson, Yonah Lewis, Calvin Thomas, Pavan Moondi,

Luo Li, and Andrew Cividino. TIFF recently put together their Canada’s All-TimeTop Ten List which includes Atanarjuat,

Mon oncle Antoine, The Sweet Hereafter, Léolo, Jésus de Montréal, Goin’ Down

the Road, Dead Ringers, C.R.A.Z.Y., My Winnipeg, Stories We Tell and Les Ordres. All good films. They’ll be

organizing special screenings this summer at the Lightbox to correspond with

the list, which has just been published in the new issue of Montage. But these eleven titles are

just the tip of the iceberg in terms of note-worthy Canadian cinema. TIFF again

has an annual Canada’s Top Ten and there are the Canadian Screen Awards which

highlight some of the best Canadian films each year. There are exciting films

festivals in Toronto like TIFF, Hot Docs and Images where they even play a lot

more Canadian films. There are serious film magazines like Cinema Scope, Point of View, and 24 Images where these films are discussed and the directors

interviewed. I’m not one to necessarily be too patriotic but we have it pretty

good here and our national cinema is pretty impressive in its diversity.

There’s even now a National Canadian Film Day. There’s something to be proud of

in all of this.

We’ve got some

good directors in Canada. To make a short list there’s Jean-Marc Vallée, Guy

Maddin, David Cronenberg, Denis Côté, Sarah Polley, Stéphane Lafleur, Kazik

Radwanski, Igor Drljača, Matt Johnson, Yonah Lewis, Calvin Thomas, Pavan Moondi,

Luo Li, and Andrew Cividino. TIFF recently put together their Canada’s All-TimeTop Ten List which includes Atanarjuat,

Mon oncle Antoine, The Sweet Hereafter, Léolo, Jésus de Montréal, Goin’ Down

the Road, Dead Ringers, C.R.A.Z.Y., My Winnipeg, Stories We Tell and Les Ordres. All good films. They’ll be

organizing special screenings this summer at the Lightbox to correspond with

the list, which has just been published in the new issue of Montage. But these eleven titles are

just the tip of the iceberg in terms of note-worthy Canadian cinema. TIFF again

has an annual Canada’s Top Ten and there are the Canadian Screen Awards which

highlight some of the best Canadian films each year. There are exciting films

festivals in Toronto like TIFF, Hot Docs and Images where they even play a lot

more Canadian films. There are serious film magazines like Cinema Scope, Point of View, and 24 Images where these films are discussed and the directors

interviewed. I’m not one to necessarily be too patriotic but we have it pretty

good here and our national cinema is pretty impressive in its diversity.

There’s even now a National Canadian Film Day. There’s something to be proud of

in all of this.Tuesday, April 28, 2015

Hot Docs 2015: The Nightmare

Is Rodney

Ascher’s new documentary The Nightmare

essentially about Stanley Kubrick? The ostensible subject is sleep paralysis…

but I actually think it continues his previous doc Room 237 by looking at Kubrick’s lessons and how they apply to the

modern world. Even in Ascher’s description of his own sleep paralysis what he

describes is pure 2001. In The Nightmare Ascher explores the

subliminal messages behind Danny’s hallucinations in The Shining and the nightmare secret society of Eyes Wide Shut. What exactly was Danny seeing in the Overlook? What was Bill

Hartford closing his eyes towards? What was Kubrick trying to warn us of? The Nightmare, actually very similar to the recent It Follows, shows a

world under attack by these supernatural forces. Save yourself if you can.

Hot Docs 2015: Raiders!

“Did you get the shot?,” asks an explosive technician after he regains consciousness after being knocked out by a plane that blows up five-feet away from him. Growing up in a middle-class household in Mississippi in the Eighties two teenagers, both from divorced parents, escape the sadness and boredom of their lives by deciding to re-create shot-by-shot Raiders of the Lost Ark. What’s so incredible is, with the help of many other kids in the neighborhood, they actually manage pull it off, even though by the end of filming the two friends had stopped talking to each other. Now that they’re both older and they’ve have the chance to reunite they decide to take time off from their work and live to recreate the ending that they couldn’t have filmed at the time: a huge brawl in front of a plane and camel which involves some serious pyrotechnics.

It goes without

saying that Steven Spielberg has influenced countless people worldwide throughout

successive generations. What’s so impressive here is to see how even when his

earlier films were just getting released that they could so profoundly affect

these boys and affect them for life. For a few scenes alone this documentary is

worth seeing: after sending Spielberg a VHS tape the principal creators of the Raiders Adaptation are invited to

Universal Studios to meet the master. This is every Spielbergian dream and you

can live it vicariously for a few minutes.

Monday, April 27, 2015

Run for Sublet !

Lev Lewis

currently has a Kickstarter for his directorial debut Sublet. It’s about a young woman who wants to get away from her

troubled home and takes that opportunity when she meets a rich man. The cast

includes Melanie Scheiner (Soft in the

Head), Deragh Campbell (I Used to Be

Darker) and Claudia Dey (The Oxbow

Cure). It sounds like an interesting project. Lewis has already worked on

making films with his brother Yonah and friend Calvin Thomas. These three films

Amy George, The Oxbow Cure and the

upcoming Spice it Up stand out for their

originality and economic approach to filmmaking. Contribute if you can. We need

more Sublets in the city!

***

Wednesday, April 22, 2015

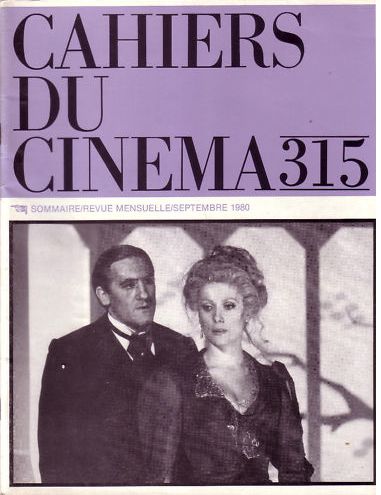

Positif on Cahiers in the Eighties

-->

It is worth

bringing up the magazine’s rival Positif

to have a better understanding of what was unique to Cahiers in this period. They had both been around since the early

Fifties and their collective archives provide an impressive film history of the

periods since then. In their early years, during the height of the Cold and

Algerian War, Positif defended social

films while Cahiers isolated cinema

to study their auteur and Hollywood

studio films of predilection. In the early Sixties, Gérard Gozlan at Positif would criticize the guiding Cahiers maxim of Bazin’s Christian-spirituality

and then afterwards Cahiers, while

also getting mobilized with the political fervor of the times, would go on to a

decade-long hiatus of films as popular entertainment. Even though Positif would evolve, through different

editors and publishers over the years, they never had this extreme of an

identity crisis.

Positif

never had like Cahiers superstar film-critics,

nouvelle vague directors and a decade

of political mobilization. But once Toubiana would start to run the magazine as

a regularly monthly film magazine in the Eighties it would slowly start to

resemble more Positif. As well Positif, which kept a regular activity

throughout the Seventies, had an advantage over Cahiers as they had a head start on covering many of the directors

that would start to rise to prominence throughout the Eighties. The two

magazines would both attend the major film festivals Cannes and Venice; and

this French and European art-house cinema would be the centerpiece for both

magazines, while still being able to appreciate certain new American auteurs.

The

differences between both magazines are subtler in this period. Cahiers had the Journal section, Jean-Paul

Fargier and his writing on video-art, special travel issues (U.S.A., China,

U.S.R.R.), and significant American contributors like Bill Krohn, Bérénice

Reynaud, Jonathan Rosenbaum and Todd McCarthy. Historically Positif always preferred British cinema

which they did a better job at representing. Their collaborator from England in

this period was Mark le Fanu who would write on the subject. But they also

shared different conceptualizations of what was the ‘Classic’ period of cinema

and what was its ‘Modern’ period. There was always a side ‘Tradition française’ at Positif

and this was illustrated in their taste for Alain Resnais and Bertrand

Tavernier while Cahiers was more nouvelle vague and had their own

directors.

But

their rivalry never descended into the maelstrom of fights and name-calling of

their early years. It seems like both magazines had a good amicable working

relationship in this period. The rivalry is never explicitly brought up either.

Some of the new Cahiers critics –

Nicolas Saada, for example – would have even studied cinema in university under

like Michel Ciment. Toubiana and Cahiers

would even come to the support of Positif when they had a quarrel at the beginning of

the Nineties with its publisher regarding copyrights.

But

even though Michel Ciment and Paul-Louis Thirard would say that their rivalry

is something of the past to look at Positif

a little more closely it would appear that they still held a grudge against

their more ‘popular’ counterpart. Positif

begins the decade still on some of their old fights with some of the older Cahiers critics like Skorecki and

Commolli. They would also ridicule their serious Marxist film theory and that of

other magazines like Tel Quel. While Thirard,

and others from Positif, would

criticize Cahiers for the ignorance

of Positif and the books by some of

its writers. In Positif instead of

addressing Cahiers they preferred to

use the space in their magazine to promote smaller, newer film magazines. It

appears that the guiding principal at Positif

in the Eighties was to just ignore Cahiers.

And any time they do bring them up it is usually just in passing and

sarcastically in their ‘Encyclopedie Permanente du Cinematographie’ and ‘Autours

du cinema’ section; or when Cahiers

authors published new books.

The

Positif critics in this period are

older and more mature and since some of them were somehow connected to the

university academy their critiques resembled more to university essays. The Positif critiques, which were all

extremely well-written and insightful, would highlight the film’s directors

reoccurring themes, motifs and etc. It lacked some of the more poetic and

polemical prose of some of the Cahiers critiques

of this period. But still the Positif

archive of this period is really rich and full of rigorous close readings of

the major films and auteurs of this period. Where Positif was more positive,

Cahiers always distinguished itself

by hating to better to be able to

appreciate what it liked. Positif

would resent and accuse Cahiers of

having, or attempting to, have ties with the film industry and for promoting

heavily the films of its own directors. Positif

would also accuse Cahiers of a

certain snobbism and of being trendy. Positif would reproach Cahiers

for saying how they ‘discovered’ all of these filmmakers when in actuality it

was Positif, as they like to proclaim,

had done it first.

But

there is also less of an evolution at Positif

than at Cahiers which really changes

and grows through its different periods. Where Cahiers seems to grow there is an impression of Positif still being ‘stuck’ or

‘cemented’ in its views from the Fifties, regardless that they are writing

about new films.

The

two important pieces for Positif in

this period are both by Michel Ciment (its current chief editor): there is one

on the tasks of film criticism and the other one is a polemic on Godard’s Soigne ta droite (N.324). Ciment, even

this early on in being at Positif (he

started in the Sixties) is starting to cement himself as a major figure at Positif. His then wife Janine would be

there too in this period – helping with translations – and is described as an

important collaborator.

Godard

would be the major opposition between both magazines in this period. Where

Godard at Cahiers is a major guiding

reference then at Positif they couldn’t

care less about him. His films were generally not even reviewed in this period.

This is why Ciment’s critique especially stands out.

In

Ciment’s critique Je vous salue Godard

he calls Godard out for some of his more obnoxious and untrue public

statements. Ciment wrote, “On the media scene Jean-Luc Godard incarnates the

modern buffoon but there’s no longer a king.” Ciment highlights Godard’s media

interviews and how he makes fun of everyone and is never contradicted. Ciment

finds it sad that at Cannes the reception is less on Godard’s films than his

press conferences. For Ciment, Godard “incarnates a period where creation is

only a pretext for a chatter of the social, political and the aesthetics.”

Ciment especially disagrees with Godard (and he has been repeating this ever

since) that cinema and storytelling is dead. Ciment does not see a personal

evolution in Godard’s films as he would see in Bergman in his contemporaneously

new book The Magic Lantern. Ciment wrote,

“By never being put into question, Godard has trapped himself in a vicious

circle and has refused to change since he’s convinced that there’s nothing to

change.” It is a significant essay for Positif

although unfortunately it is stylistically rough and has a lot of typos.

But

the Positif fight seems to be less

with Cahiers than with film criticism

in the popular press whether that is Le

Monde, Variety and Nouvel Obs. Their

aim is to try to improve film criticism in the general French film journalism

sphere. This is two-fold: there is a pedantic criticism towards lazy writing

and misinformation but there’s also a self-righteous ‘we’re right, and they’re

wrong’ attitude about it. Positif

never really had critics who became directors but instead they had a lot of

authors and cultural industry employees that would emerge.

Ciment’s

essay on film criticism is from the dossier France:

Des Deniers Critiques aux Premier Films and the title of his piece is De la critique dans touts ses etats a

l’etat de la critique (March 1987, N.313) which he dedicates to his wife

Jeannine, who would have just passed away (‘En

souvenir de Jeannine et de son exigence’).

In

it he argues with a popular press article by Michel Boujut (producer of Cinema Cinema) who complains that film

critics lacks the ability to appreciate films. The emphasis is on the

profession of critics/journalist. Ciment argues that film criticism matters and

that the importance of criticism is an old debate that goes all of the way back

to Balzac and Aristotle. Ciment reaffirms, “Criticism must not worry about the

public… The critic must be able to address what he felt and explain this

through his tools - knowledge and words.” Ciment even uses a Cahiers turn of phrase, “Le travelling n’est plus une affaire de

morale mais de tickets vendus.”

Ciment

is against this rush to be relevant. In this period Positif would have a lot of important dossiers on the history of cinema. Positif would publish dossiers on Frank Capra (to coincide with a

major new Cinémathèque Française retrospective) and early silent films like those

of the Lumière brothers (Positif’s

founder Bernard Chardère would also establish the Lumière Institute in Lyon).

Leos

Carax is also a site of contestation regarding a modern French cinema and how

to ‘publicitize’ films by making them ‘events’.

“Mauvias Sang, where there is an

undisputable talent, becomes one of the best films of film history, which we’ve

seen since Noir et Blanc by Blaire

Devers, which came out… only two weeks ago. New cinematographic film events

take place at such an accelerated rates. So the film by Carax, which Cahiers, dedicated numerous long texts

in two successive issues, and that is compared here and there to Murnau, Joyce,

Vigo, Picasso, Welles and Schonberg would then be in a few months in most of

the lists of the ten best films of the year in a lot of the publications,

especially by its collaborators in Cahiers

and their other outlets.”

Ciment

criticizes Telerama for being too

lenient (“four new masterpieces every week, they say” and he worries about the

temptation of journals to become less serious magazines to increase their sales

and reach a larger public. What Ciment is arguing for is the necessity to find

alliances to be able to put on exciting screenings and to publish serious film

criticism in France. This is what is necessary.

Toubiana's Eighties Editorship: French Cinema and Cannes

From

the time he became the chief editor of Cahiers

in 1981 until his departure in 1992 Toubiana wrote and published an estimated

230 articles which includes editorials, critiques, interviews and journal. What

stands out from his critiques is how they are able to canonize films and

directors into the Cahiers canon just

by the fact that he was writing about

them. The films that Toubiana wrote major critiques for stand out as ‘Événements’ as the film would usually be

featured on the cover and the director would be interviewed. They would also

later be cross-referenced as important films for that year. These critiques

stand out both due to the strength and interest of Toubiana’s writing but also

due to the fact that he was the patron

of Cahiers. As a journalist-critic

Toubiana usually cites interviews within his critiques and there is a loose

quality to them. He cites dialogue from memory and acknowledges that it might

not be exactly correct. It’s a writing that’s not always precise. There is also

a lot of gastronomical references in his critiques which is a trait that recalls

the earlier writing of Claude Chabrol. The critiques provide examples of what

were considered are the most important French and international films of the

year. There were two important areas of interest for Toubiana’s editorship of Cahiers in the Eighties – these are

French cinema and the Cannes Film Festival.

Of

the first area of interest, French cinema, Toubiana wrote “It is French cinema

that is our conjecture.” The French

film industry was the terrain that Cahiers

could most efficiently engage with and could help shape. The Eighties

marked the return of French cinema at Cahiers.

The important directors to spark

this return are the older nouvelle vague

directors with Godard and Truffaut at the forefront and then Rivette, Rohmer

and Chabrol. Even though Truffaut died early on in the decade he would still

retain an immense importance for Toubiana. There was a special Truffaut

memorial issue. His life and films would

be honored, in the culture at larger and at Cahiers,

with the re-release of Les Deux Anglaises

as well as by the publication of Truffaut-related books like Hitchcock/Truffaut and his Correspondences.

This

encounter with Truffaut also sparked a return towards an industrial French

cinema. Among Toubiana’s best critiques are the ones where he brings a new generation

of French directors into Cahiers pantheon.

Toubiana published major texts, whether critiques or interviews, on the

following French directors: Alain Corneau, Claude Miller, André Téchiné, Robert

Guédiguian, Claude Chabrol, François Truffaut, Robert Bresson, Raymond

Depardon, Jean-Pierre Mocky, Maurice Pialat, Bertrand Blier, Jean-Jacques

Beineix, Claude Berri, Louis Malle, Jean-Luc Godard, Michel Deville, Pascal

Thomas, Jacques Demy, Tonie Marshall, Georges Rouquier, Jean-Marie Straub and

Danièle Huillet, Marguerite Duras, Leos Carax, Éric Rohmer, Patrice Chéreau,

Jean-Claude Brisseau and Paul Vecchiali.

The

second important area of interest for Toubiana and Cahiers in this period was the Cannes film festival. It was

according to Toubiana “the grand window into world cinema” and through it the

magazine could encounter and analyze emerging directors and the trends of

contemporary cinema. By its coverage of the Cannes Festival, the biggest media

event on film, Cahiers could evaluate

the state of world cinema while at the same time improving Cahiers’ own visibility.

Toubiana

started to cover the Cannes film festival in 1981 and he continued to do so

throughout his tenure. In 1992 was even invited to the festival as a jury

member and this experience disillusioned him with regards to it. Toubiana also

covered the Venice film festival but which he saw as second-rate due the lesser

quality of the films. Italy film didn’t

benefit as much from government subsidies for culture which France had and

which Cannes benefitted from.

The

festival coverage stands out for being critical rather than sensationalist

publicity for the festival. The mediocrity of many of the films was mentioned

and a there was frustration about the festival’s disregard for smaller but more

difficult films. The directors favored by Cahiers

were put in opposition to negatively viewed academic directors showing at

the festival. The criticism by Cahiers of

some of the film festival practices made its relationship with the festivals a

little tendentious at times. This strong and dissident coverage towards the

festival was rare within the often self-congratulating cultural sphere.

Toubiana’s

first Cannes coverage, Un film-surprise

dans un festival sans, was critical of the festival. “It was a sad celebration,”

wrote Toubiana. “What bothers us the most this year are the films. There is a

nearly total absence of cinema, of the strong moments of cinema.” Toubiana

complained how the role of criticism was weakening in the face of the film’s

publicity and promotional machines. This demanded in response an increased

intensity in film criticism.

Toubiana

criticized a ‘dumb’ Mel Brooks film which received a popular reception and

instead highlighted Skolimowski’s Haut-les-main

which he discusses alongside Godard’s Ici

et ailleurs. Toubiana wrote, “It’s their secret. They are manifesto and

testament films about cinema. They pose Bazinian questions par excellence: What is this cloth which drapes over all of the

images? What motivates the movement of characters? What is a cinematic image?”

Serge

Daney had encouraged this dissidence. In a Journal contribution from 1987 Daney

brings up how the 40th anniversary of Cannes was over-saturated with

media. Daney sees the discourse of this over-mediatized festival as full of

clichés that ends up not doing it justice. This is a failure. The dissidence of

Cahiers is in opposition to the

popular press and the polite notes of many professional journalists reviewing

the festival. Daney argued that Cannes needs more criticism and less promotion,

It

will not be enough as long as the television media will only present a soft positive perspective on everything that

unfolds on the Cannes stages. What

is important is doubt, criticism and a negation. These taboos and criticism are

actually what makes a film festival. There needs to be dirt, debates, polemics,

proclamations and swoons because without these the festival would only be a simulacrum

and nothing but noise. The festival only works through its negative moments – through a process that denies it. This is

necessary for it to finally becoming itself. Through this negation there can

finally be an event at the festival.

***

Cahiers and Truffaut : A Reconciliation

-->

In the early Eighties

at Cahiers French cinema became a

renewed area of interest and this was celebrated in their two special 30th

anniversary issues (May and June 1981). Through these issues Cahiers were able to strengthen their

ties with the French film industry and its producers, directors and actors.

Even though articles on Godard had already been a standard feature since

Daney’s early editorship now finally the rest of the nouvelle vague directors would become a renewed area of

interest for the magazine.

In

1980 Daney and Toubiana met Truffaut in an effort of reconciliation as he had

been actively neglected from the magazine. They discussed the new philosophy of

the magazine and requested help with financing that Truffaut would help to

arrange. After their meeting Truffaut would say that he now had an ‘open

neutrality’ towards Cahiers.

As a result of this meeting, a lengthy interview with Truffaut would follow and

would be published throughout two issues in 1980. It builds upon the two

previous interviews with Truffaut. (This makes Truffaut the less interviewed nouvelle

vague director. The

other interviews include with Jean Collet, Michel Delahaye, Jean-André Fieschi

from December 1962 and with Jean-Louis Comolli and Jean Narboni from 1967).

The

Événement film that sparked the encounters with Truffaut was Le Dernier Métro. The film was publicized on the magazine’s cover and a

positive review, Une nuit au theatre

by Yann Lardeau, was printed

along with the interview. Truffaut, who represents French popular cinema,

received an equal amount of attention as Godard.

The

first part of the Truffaut interview by Daney, Narboni and Toubiana appeared in

the September 1980 issue. The Événement was prefaced by Toubiana, Truffaut ou

le juste milieu comme experience limite. The last interview the magazine had done with Truffaut was

in 1967 (which was entitled, Le juste milieu) for Fahrenheit 451, and since then Truffaut made 13 more

films.

Toubiana

wrote,

There

was thirteen years of silence or non-dialogue (there were some critiques of his

films, but no interviews) between us and Truffaut because of our attachment to

theory and our political chores. What we were looking for in the Seventies were

what you could call limit experiences – far from the ‘juste milieu’ which preoccupied Truffaut.

Toubiana then argued

that what Truffaut was doing at the juste milieu was a limit experience of the center of

French society and film production. The extreme qualifier is that Truffaut was

making the films that he wanted to make and he had the independence to

make them through his own production company. It’s a paradoxical and

contradictory proposition. Truffaut is not trying to distinguish himself from

the other professionals in the French film industry but he’s not part of the

Qualité française which he in the past denounced. Toubiana’s perspective offers

a different way to look at Truffaut’s more conventional works. Cahiers was in perpetual evolution and it

constantly tried to gaze beneath the surface of things.

In

the interview Truffaut was very frank and modest. On his work as a director he

said, “Finally, what makes me the happiest about cinema is that it gives me the

best job possible.” “I don’t

see an incompatibility between the terms auteur and professional.” “I work better

with director-producers that work hard - Rohmer, Mocky, Berri – than with those

that complain like spoiled children that deserve everything.” On Godard, who he

thought was ‘compulsively jealous,’ Truffaut undermined his more high-minded

statements by showing the simple, uncaring arguments behind them:

When

Rivette received one of the largest advances on receipts - 200 million for four

films - Godard went after him in Pariscope. ‘The pleasure of Rivette is the same as

Verneuil but it’s not mine. Rivette has no longer any humanity.’ And then it

was Rohmer’s turn when everyone admired La Marquise d’O, Godard criticized it. When Resnais won six or seven Césars for Providence, Jean-Luc, as you can expect, turned

against him saying ‘Resnais hasn’t

made any good films since Hiroshima.’

On

his distancing himself from Cahiers, Truffaut said

“I’ve stepped back from Cahiers

since the day where I made my first film. I had the sense of changing camps

[from critic to filmmaker].”

The

interview with Truffaut signaled a major shift at Cahiers from Daney’s often enigmatic editorial

stances to Toubiana’s more populist ones. Godard would not necessarily be

dropped but he would no longer be as fetishized. Truffaut and other

popular French directors would start to get equal coverage. Cahiers and Toubiana, drawing from Bazin,

Truffaut, Hitchcock, and Chaplin, would show how strong personal art works

could be created within the popular film industry.

Monday, April 20, 2015

RIP Manoel

“It was clear to Daney that a critic that

couldn’t tell the difference between a long-take for de Oliveira (the opera

scene in Francisca) and the

long-take for Angelopoulous (who shows everything right away to then not have

to do any more work) isn’t good enough to write at Cahiers.” – Charles Tesson

***

***

***

***

***

***

A Must-Have: Wild Blu-ray

Ouf! Putting

together a trekking-pack and then off to hike the PCT! It’s not going to be

easy for poor Reese but she’ll do it and it’ll be memorable. With the release of

Wild on Blu-ray you can now join her

either for a casual stroll or to closely examine each step. It’s well worth it

since there’s a lot that’s tucked away in Wild.

The location of the opening scene where Reese loses her boot took the crew a

whole morning to get to as they had to take two chair lifts and then walk

twenty minutes to get there! The fox, which is her spiritual guide for the

journey, has more appearances than you might think. The scene where Reese is

getting a martini the bartender is actually played by Vallée’s son Alex. Who

knew that with the visual effects technician Marc Côté that a lot of the

landscapes scenes were digitally altered? And the scene at the end when Reese

gets to the Bridge of the Gods it’s actually Cheryl Strayed’s husband and son

that wave to her. These are just a few examples of how Vallée meticulously

crafts his films and makes them personal. He’s the exception to the rule and

clearly illustrates how Hollywood can still produce great works of art. This Blu-ray of Wild is one of the best new DVDs of the

year just for Vallée’s audio commentary. It’s good to hear him talk about his

craft and to hear how he’s settling into Hollywood. The many making-of

featurettes, deleted scenes with commentary, and an impressive gallery section

also contribute to making this a must-have for all Valléeians.

Thursday, April 16, 2015

Hot Docs 2015: Searching for Charlie Mortdecai

“They said we couldn’t do it!” – Will Sloan

The local

Twitter-personality Will Sloan explores in Searching

for Charlie Mortdechai the cult phenomenon which is the 2015 action comedy Mortdechai. From its early theatrical

release (which was unfortunately cut short), to its special one-time screening

at The Royal, and its afterlife through its plethora of merchandise – Mortdechai had been with Sloan for quite some time. In this documentary Sloan explores the roots of

the character (who owes a lot to Johnny

English), examines his ethnicity (could he be Jewish?), and closely

analyzes the film that Positif described

as “It’s not that bad!” Sloan puts himself in the documentary and you get to follow him on a trip to London to explore the Mortdechai Mansion (they don’t let him in) and to

Mumbai for an exclusive interview on the film for the India Times. Searching for

Charlie Mortdechai is a hybrid doc that's somewhere between Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy and Rodney Ascher’s Room 237. Through Sloan’s

adventure to peel away the magic of the cinema screen the documentary presents a light-hearted

and complex examination of people’s relationship with movies.

Screenings:

- Hot Docs

Cinema – Sun April 28, 3:15 PM

- Scotiabank Theatre

5 – Mon April 29, 8 PM

- Royal Cinema –

Sun, May 3 3:15 PM

A Must-Read: Shelly Kraicer on Luo Li

"Over the last six years, Luo Li has established himself as one of the most interesting young Canadian directors on the international festival circuit, and one of the most promising Chinese independent directors to emerge in the last decade. Marked by narrative playfulness, implicitly subversive formal innovation, and elegant, beautifully crafted images, and pervaded by a remarkably gentle, unassuming confidence, his four features have already staked out something like a Luo Li universe."

Follow the link to read Shelly Kraicer's essay Of Time and the River: Mapping the Cinema of Luo Li in the new Cinema Scope.

Follow the link to read Shelly Kraicer's essay Of Time and the River: Mapping the Cinema of Luo Li in the new Cinema Scope.

Tuesday, April 14, 2015

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Les Fleurs Magiques

The only place

that you can find Jean-Marc Vallée’s Les

Fleurs Magiques on video is at the Cinémathèque

québécoise. It’s one of his early short films. What’s so impressive about it is

how it anticipates many of his later themes and stylistics. If Vallée speaks about an affinity for Les Bons

débarras it's in this film where it’s the most present. If there’s a

running theme throughout Vallée’s cinema it is of loving so much that it hurts just like Manon in the film of Francis

Mankiewicz. In Les Fleurs Magiques

there’s a little boy (Marc-André Grondin; fascinating to see just as a child)

who wants to help cure his father from being a drunk. The boy is also really

close to his mother, who he admires for her good nature and strong qualities.

The only place

that you can find Jean-Marc Vallée’s Les

Fleurs Magiques on video is at the Cinémathèque

québécoise. It’s one of his early short films. What’s so impressive about it is

how it anticipates many of his later themes and stylistics. If Vallée speaks about an affinity for Les Bons

débarras it's in this film where it’s the most present. If there’s a

running theme throughout Vallée’s cinema it is of loving so much that it hurts just like Manon in the film of Francis

Mankiewicz. In Les Fleurs Magiques

there’s a little boy (Marc-André Grondin; fascinating to see just as a child)

who wants to help cure his father from being a drunk. The boy is also really

close to his mother, who he admires for her good nature and strong qualities.

Let’s run Les Fleurs Magiques through the Vallée

checklist: Good use of classic popular music? Check! A Christian spirituality

and a faith in the world? Check! A subjective poetic point-of-view and elliptical

editing? Check! Artworks and creation as personal and carthartic? Check!

So you see all of what makes Jean-Marc Vallée’s work so singular is already there in one of his earliest short-films! I don’t know about you but I’m really impressed.

So you see all of what makes Jean-Marc Vallée’s work so singular is already there in one of his earliest short-films! I don’t know about you but I’m really impressed.

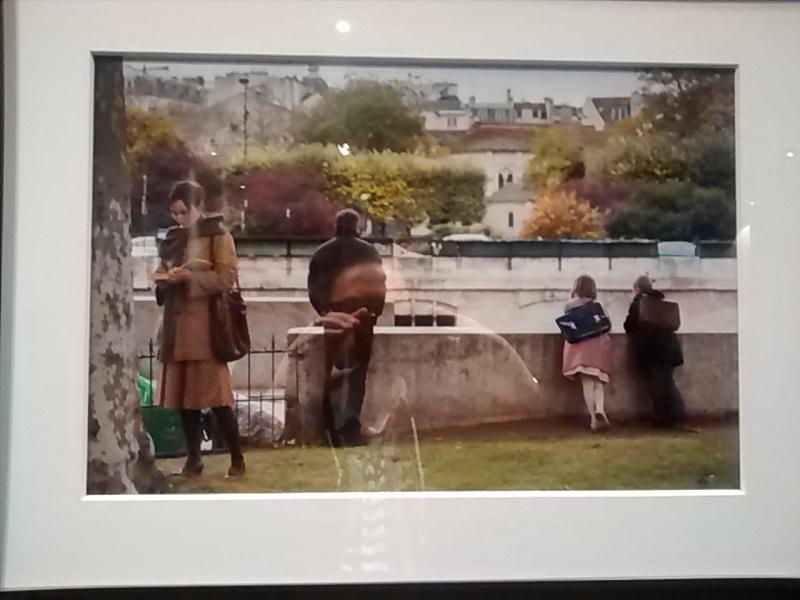

Also at the Cinémathèque

was a Sébastien Raymond photography exhibition Un temps d’acteur which included behind-the-scenes photographs from C.R.A.Z.Y.

and Café de Flore. What’s so

impressive about these is how they display Vallée’s process, contemplation and

precision. In one photograph he’s in a church standing behind Michel Côté and

analyzing its rhythm to best direct the scene. In another Côté is standing

outdoors by a trailer getting into character before an emotional confrontation

with his son. There’s introspection and personal drive that goes into making these

works and this comes across through the photographs. The ones of Paris for Café de Flore are especially

interesting to see the solitude and intimacy of a Vallée set.

Also at the Cinémathèque

was a Sébastien Raymond photography exhibition Un temps d’acteur which included behind-the-scenes photographs from C.R.A.Z.Y.

and Café de Flore. What’s so

impressive about these is how they display Vallée’s process, contemplation and

precision. In one photograph he’s in a church standing behind Michel Côté and

analyzing its rhythm to best direct the scene. In another Côté is standing

outdoors by a trailer getting into character before an emotional confrontation

with his son. There’s introspection and personal drive that goes into making these

works and this comes across through the photographs. The ones of Paris for Café de Flore are especially

interesting to see the solitude and intimacy of a Vallée set.

Though Vallée

has discussed later expanding Les Fleurs

Magiques into a new feature I don’t know if this is necessarily a good idea

(even though I’m sure it would still be amazing; it would further align him

with the Spielberg of E.T.). By

continuing to make new films and tell these new stories he’s multiplying his registers

and creating a fascinating larger universe. Les Fleurs Magiques would then be the seed to these beautiful

flowers that he’s now creating. Things are blossoming for Vallée.

Hopefully Demolition will play at Cannes or

another important fall festival (and get the reviews that it deserves – he was

just honored with a Governor General Award which is a good start) and then there’s

his Janis Joplin biopic and his adaptation of Dominique Fortier’s Du

bon usage des étoiles

(which I’m especially looking forward to), which seems like the best reference

to capture his ethos. He’s a lone adventurer sailing into the mysteries of the

world and more importantly: of the human heart.

Thursday, April 9, 2015

A Must-See: Gurov and Anna

The films of Rafaël

Ouellet are sad. In them the world is grim and people aren’t happy. This is a

given. If the working class characters in Camion

were depressed then Gurov and Anna

can reassure us that the middle

class also has its problems. It’s about an English professor Ben who,

obsessed with Chekhov’s The Lady with

the Dog, decides to have an affair with one of his students Mercedes. If

this story of a perverted old creep trying to get with one of his students

sounds familiar it’s since it is. Gurov

and Anna especially recalls the chamber dramas of a Bergman or an Allen. Luckily

there’s more to it. The filmmaking and its atmosphere are exceptional. Ouellet

is able to transcend some of the film’s clichés to get at the heart of things and to the human condition. Seeing Ben slowly loose control of his life and have his wife and lover, who become better writers than he is, leave him touches

upon the frailty and vulnerability of modern masculinity. There is a side Winter Sleep to Gurov and Anna. When Ben walks around Montreal in his awkward winter

coat and hat, creeping around street corners there is an air of Nosferatu about him. But what's especially

noteworthy is Sophie Desmarais as Mercedes. It’s a complex role and Desmarais gives her depth. Her sweet and artistic air within a

confusing and troubling modern life in Montreal especially recalls the earlier Carole Laure

performances in the films of Gilles Carle. There’s a couple of great scenes of

Desmarais on a stage at a café reading some Checkov. She gives the words a

whole new meaning through her interpretation and emphasis. If Québécois cinema already has

its musicians (Stéphane Lafleur), Hollywood types (Jean-Marc Vallée), and

outsiders (Denis Côté) then with Gurov and

Anna Rafaël Ouellet places himself as one of its foremost playwright director.

The films of Rafaël

Ouellet are sad. In them the world is grim and people aren’t happy. This is a

given. If the working class characters in Camion

were depressed then Gurov and Anna

can reassure us that the middle

class also has its problems. It’s about an English professor Ben who,

obsessed with Chekhov’s The Lady with

the Dog, decides to have an affair with one of his students Mercedes. If

this story of a perverted old creep trying to get with one of his students

sounds familiar it’s since it is. Gurov

and Anna especially recalls the chamber dramas of a Bergman or an Allen. Luckily

there’s more to it. The filmmaking and its atmosphere are exceptional. Ouellet

is able to transcend some of the film’s clichés to get at the heart of things and to the human condition. Seeing Ben slowly loose control of his life and have his wife and lover, who become better writers than he is, leave him touches

upon the frailty and vulnerability of modern masculinity. There is a side Winter Sleep to Gurov and Anna. When Ben walks around Montreal in his awkward winter

coat and hat, creeping around street corners there is an air of Nosferatu about him. But what's especially

noteworthy is Sophie Desmarais as Mercedes. It’s a complex role and Desmarais gives her depth. Her sweet and artistic air within a

confusing and troubling modern life in Montreal especially recalls the earlier Carole Laure

performances in the films of Gilles Carle. There’s a couple of great scenes of

Desmarais on a stage at a café reading some Checkov. She gives the words a

whole new meaning through her interpretation and emphasis. If Québécois cinema already has

its musicians (Stéphane Lafleur), Hollywood types (Jean-Marc Vallée), and

outsiders (Denis Côté) then with Gurov and

Anna Rafaël Ouellet places himself as one of its foremost playwright director. Wednesday, April 8, 2015

Nick and Sam

Cahiers had always approached American cinema from a detached European

perspective. In this regard two of Daney’s most important critiques from his early

Eighties period are the ones on Wim Wenders’ Lightning Over Water and Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One. These

were important films and critiques for bridging the classic Cahiers jaune era with the modern cinema

of the Eighties. Daney encouraged this external contemplation of Hollywood and

this is why his favorite American films also implicitly participated in this.

Other examples include the films of John Cassavetes, who made his home movies next door to the Majors in

California, and Barbara Loden and her only film Wanda.

There was always

a side film malade to Daney

(Truffaut’s term to discuss Hitchcock’s Marnie).

For Daney it is these sick films that

are more representative of cinema globally and Daney personally. The

documentary by Wenders met en place Nicholas

Ray’s frail and dying body which for Daney offers a surrogate for the status of

the Classical Studio era. Lightning Over

Water is seen as a film about the politique

des auteurs, where a director’s failure is seen as the more personal work

than the success, which for Daney has now become corrupted as a marketing tool.

The new European

director in this period that best addressed these concerns for Daney was Wim

Wenders. There was Lightning Over Water

but also before this The American Friend where Wenders would cast Fuller and

Dennis Hopper. There is a Godardian, Le

Mépris quality to these films in their reflexivity and criticality. Daney

in his critique of Lightning Over Water

highlights its perversity which is similar to Ray’s own cinema, “The subjects

of Ray’s films is less revolt than the impossibility of revolt.” Daney’s

description of the relationship between Ray and Wenders in Lightning Over Water can equally be read as a commentary on the

relationship between different generations at Cahiers. “It’s about this

alliance that is forced due to a filiation, where this filiation is experienced

like an alliance. This is the cinema of Nicholas Ray. But also, this

relationship, experienced at the

beginning of the Eighties, becomes a way to recount the history of cinema.”

Serge Le Péron

would pick up on Daney’s analysis in his critique of Wenders’s Hammett. Le Péron writes, “For another time it is a fiction about

filiation that Wenders is confronted with.” To make the film, Wenders had to

learn the old ways of studio filmmaking and the film, which is produced by

Francis Ford Coppola, can be divided, according to Le Péron, with its story that belongs to its producer and

its images that belong to its

director. This emphasis on the director, framing and mise en scène leads Le Péron to concluding on its modernity, “For

his tenth film, with its ancient narrative and retro production, Wenders’

preoccupations are never that far away from those of Godard and Antonioni.”

Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One, similar to George Cukor’s Rich

and Famous (which was also

featured in this period), is a late testimony film by one of the last old studio

directors. Even though Daney laments that the four-hour version will never get

properly released (which is no longer the case) he still describes Fuller’s The Big Red One as, “It’s the best film

by Samuel Fuller, and nonetheless the most personal and ambitious.” Fuller’s mise

en scène

and morality remained intact and there’s a serenity to the film that comes from

old age. Daney continues,

If Fuller was

adopted at Cahiers like a modern

filmmaker it’s because, more than any other American, he’s a filmmaker who is

obsessed with the idea of the contemporary…

Even when he was telling stories that were set in the past there was always the

sentiment of ‘the first time’. This was new to the cinema. It was as if nobody

had filmed before him… This came from how Fuller was both a wartime journalist and also a mad journalist.

Daney is

building upon Godard’s earlier legacy as a film critic and filmmaker. He’s

creating an explicit filiation with the author of one of the most famous Cahiers critiques which is that of

Godard on Bitter Victory (“Nicholas Ray is cinema…”) and of Godard

the director of Pierrot le Fou where he would cast Fuller in a small

role to discuss his wartime experiences and cinema.