Everything good

comes to an end. And there’s always something next. Serge Toubiana, who

miraculously re-launched Cahiers in

the late Seventies, and then spent over twenty years there as the chief editor,

sometimes with others, spearheaded it to the forefront of relevance,

reconnecting it to is past glory, and successfully made it more international.

His legacy is important there today in the Stéphane Delorme years even though

this influence is invisible. It is one of unabridged cinephilia, generosity,

seriousness and criticality. As the director of the Cinémathèque he brings the

heritage of the magazine and of cinema to a national and international level. As his recent

interview in Cahiers (N.699) attests

he continues a tradition started with Henri Langlois. Toubiana might be less

known for his criticism (though some of his critiques are amazing, the one on Deconstructing Harry comes to mind)

than for the guiding and composing of the issues, evolving with the times, and

recruiting and refreshing a good team of film critics. He imposed himself on

the issues through his pressing editorials, Cannes coverage, and by the

implementation of the Le Journal section. Serge Daney would be his intellectual

and spiritual counter-part. So where Daney kept on the Godardian tradition of

cinema as a tool of social protest where images held a Bazinien ontology that

interrogated the world, Toubiana kept the Truffautian tradition of spectatorship

reverie, biting polemics, and of an optimism mixed with melancholy. The

book Postcards from the Cinema (unfortunately out-of-print), which is a lengthy interview between them, concludes their

beautiful friendship. When the magazine updated it’s format in the early

Nineties and they featured Jacques Doniol-Valcroze it was a subtle reminder of

this mise en page tradition that

Toubiana himself was keeping on. As well with Antoine de Baecque’s two-part

history being published in this period this was when a Cahiers

self-consciousness was emerging.

If one looks at

the subsequent chief editors one can make certain assumptions of their guiding

taste by the representative American directors they most associate with: For

Thierry Jousse (‘91-‘96) it is David Lynch, Antoine de Baecque (’96-’98) it is

Tim Burton, Charles Tesson (’98-’03) it is Martin Scorsese, Jean-Marc Lalanne

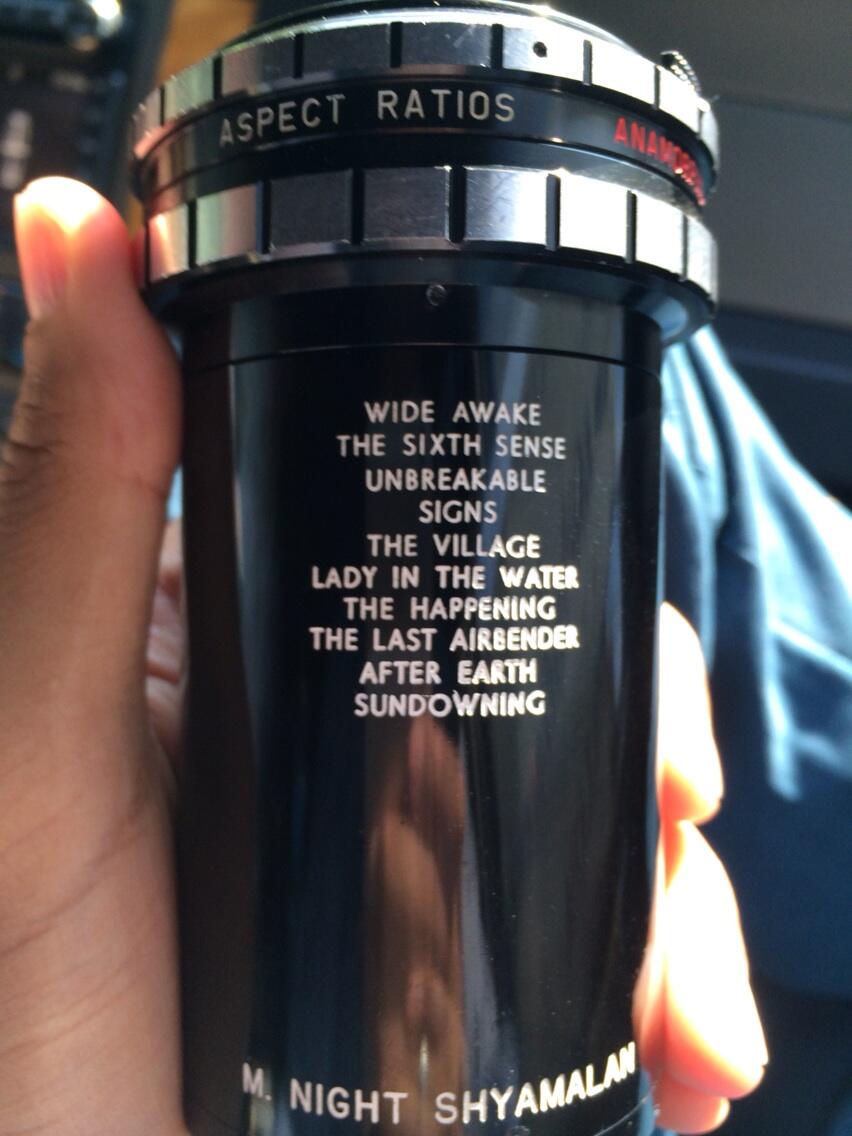

(’01-’03) it is James Cameron, Emmanuel Burdeau (’03-’09) it is M. Night

Shyamalan, Jean-Michel Frodon (’03-’09) it is Clint Eastwood, and for Stéphane

Delorme (’09-’14) it is Steven Spielberg.

If Tesson’s

editorialship is so highly regarded it’s for the generosity of his prose,

knowledge of Cahiers history, and

openness to a social and poetic cinema. It stands in opposition to his

successor. Some problems with the Frodon editorialship includes: a self-important

tone, too much reliance on the business

instead of the art of cinema, too much reliance on journalism

instead of criticism, not having too

strong of a personality, being guilty of a weird favoritism, poor economic practices

and unsuccessful managing of the magazine, and branching out the magazine too thin by exploring new outlets,

publishing and distribution. His contribution to the Les petits Cahiers on

“Film Criticism” is especially unnecessary. But it was also a complicated

post-9/11 period with the rise of the internet and its new register of digital

images, the growing DVD market and the autodidact cinephile, and the declining

relevance of cinema as a social-communal past time.

Tesson, on the other hand, is a pure

Cahiersiste. It is a spirit that

animates the magazine from within (see how he refers to the magazine as having a

heart) and it comes from a place that holds the magazine at a very high esteem – an instrument and measure of the cinema and of our times. In his texts he shares the

personal experience of being within – almost like a making of (c.f. Fissures at Cahiers). Tesson now programs at the Critic’s Week at Cannes which

continues his criticism in a different register. He has a close relationship

with the Delorme editorialship as he programs the films Cahiers champions and sometimes contributes to the magazine, notably his piece Peut-on

être rohmero-rivettien? in the Rohmer memorial issue (N.653).

The following is

Toubiana’s farewell letter from when he left the magazine in 2000 and Tesson’s when

he would leave too a few years later. – D.D.

***

Aux lecteurs,

It’s with

sentiment and friendship that I inform you of my departure from Cahiers du Cinema. I’m leaving in

effect, at the end of February 2000, my post of chief editor, as well as

co-runner of Editions de L’Etoire. This decision has been brewing in me for the

last few months. I needed to make this decision, and it was difficult to make.

One never easily leaves a magazine, especially this one, where one has spent twenty-five years of the important

years of one’s life. But it is now the case… I’m relieved that others, those

who are younger and newer, are assuming to be in charge and to guide, orient,

and enliven this magazine that we hold in such high esteem, you and me. Cahiers imperatively needs a new spirit,

a new perspective, because the cinema is changing, evolving, transforming, just

like its environment. A new spirit and a new dynamism, founded on a critical

approach and oppeness, because at Cahiers,

more than elsewhere, is entrenched in this experience for half-a-century. The

history of this magazine, rich and fecund, allows to imagine the present and

the future with serenity and confidence. There is then all the reason to

believe that Cahiers will soon be

ready for this new start, that its rendezvous will be met this year, 2000. Its

writers see themselves as reinforced by the arrival of Franck Nouchi, who will

be in charge of the direction of the magazine, with beside him Charles Tesson.

He is coming back to prepare a new format to the magazine, to respond to your

expectations, and those of the cinema. I wish them good luck, and I address

you, dear reader, my most loyal thoughts.

Serge Toubiana

***

Aux lecteurs des Cahiers

The editorial

that I wrote for the summer issue (N.581) ended with serious thoughts about the

obstacles that was shaking up the magazine last January (a project to

reorganize the editorial team) where we proposed to share our solutions in

September. The editorial of September, which was signed by Jean-Michel Frodon,

who was named the director of the magazine on the first of July, was itself an

answer to the previous editorial. His nomination to a poste that was removed

since the return of the magazine to Le

Monde where Franck Nouchi ended entirely my functions as chief editor all

the while giving them to Jean-Marc Lalanne. Since then, there has been more

changes: departure of Lalanne, which was voluntary or was expected by several

writing comity members, and instead there was the nomination of a new chief

editor, Emmanuel Burdeau, who himself was an old member of the writing

committee…

At the time of

leaving this magazine, I wanted to saw a few things. My first thought goes

towards the reader, numerous, anonymous, and familiar. There is the writer that

one imagines and that we are addressing when we put together each issue. There

is the other one (the same?) who is there (even though he might be invisible)

when we write. We can write a review by addressing the film, cinema in its

entirety, to be read by the director, or even with the desire (crazy, but

actual) to be read by such and such actor or actress. There is no true art of aimer without a certain (critical) sense

of declaration, for its form and its depth. We can also write for those who are

no longer with us (the dead) or just for oneself (a long monologue to help

guide the cinema or to thank, ad infinitum, the vital pleasure that is procured

of renewing one’s relationship with cinema). We can be attached for one’s whole

lifetime to only one aspect of this writing or by changing, according to the

nature of each film or the times or one’s relation to them. Adressing others,

however the form it takes, seems to me to be essential. Without this conscience

towards others (to convince, enlighten, share an emotion, build upon its

foundation, etc.) there is no veritable critical impulse. History, in its long

form, and not being lonely, and to share with words, with films, is one of the

pleasures that makes life livable.

My second thought goes towards those who I've worked with at

the heart of this magazine (who I've met and learnt to appreciate, and to those

that have I've become friends with, which I'll need to thank Cahiers for

bringing us together at an important time in our lives) as well to those that

I've had the pleasure to meet, whether it is in France or at the four corners

of the planet, through the function that I've occupied. A great moment of

happiness for me were the exchanges with those, who were really attached to the

magazine, that wanted to dialogue with those that contribute to it, and not

only through written correspondences. That said, internally, once we start to

have some responsibility in creating this magazine, everything changes. Because

the job of being the chief editor is one that is learnt and it has strictly

nothing with that of the exercise of criticism. Because the pressure is there,

and it's enormous. Because one has to learn within the heart of these multiple tensions,

between the divergent points of views and the sensibilities of the writers

expressions. And especially, being able to accept and overcome them, as soon as

they manifest themselves at the interest of the magazine, so that it can become

a living space, that is also rich in contradictions. So that it is not a space

that is too homogeneous (the terrorizing and terrorist phantasm of a sole

editorial line, where truth is incarnated in only one person, with an

uncomfortable corollary, which leads to a written film criticism that is

cloning and uniform, within an absolute and unique model) nor too heterogeneous

(the heteroclite cohabitation of diverse interests, in a Proteus form, for a

reader that can't make sense of everything, who is usually a minority, and who

would not be able to draw pleasure). In the context and with the conditions

that were particular to my experience, between the participation and majority

financial takeover of the magazine by Le Monde in 1998 and my nomination

to an important role of responsability that lasted until July 2003, I've tried

to bring my best all the while sharing the task and responsibility with others.

Between 1998 and 2003, amongst a changing team, I've with Antoine de Baecque

(up too April 1999), with Serge Toubiana (up to January 2000), with Delphine

Pineau (up too September 2001), with Frank Nouchi (from February 2000 to

December 2001) and then with Jean-Marc Lalanne, starting in October 2001.

My last thought goes to two people,

who if it wasn't for them my adventure at Cahiers, fabulous and unique

more often than not, awful sometimes, would never have happened. Serge

Toubiana, firstly, who, in May 1998, proposed to me to work beside him, as the

director of the magazine and then as its chief editor. And afterwards Serge

Daney. I started out just reading him, I followed at the time his courses on

the cinema at the Censier and I've confided in him my desire to write at the Cahiers,

a crazy dream (but true nonetheless) because I was really intimidated, see very

perplexed, with the idea of concretely sharing the pages with those that I've

enormously appreciated their writing (aside from Daney there was Oudart,

Bonitzer and Narboni). One day, Serge Daney sent me a message (I didn't have a

telephone at the time), marvelously laconic, that only said this: "there

are two or three films that Cahiers risks not discussing in their next issue.

For you to see them." In this list of three films, there was a

Japonese film, An Actor's Revenge by Kon Ichikawa. I saw it at the

cinema on that day, and I wrote the critique in a rush, and Serge Daney

accepted the text immediately, without any hesitation nor any modifications. It

was published in the June 1979 issue (N.302). I was then the happiest that I

can be. For a long time, a really long time, writing at Cahiers, being

part of this magazine, to be installed more or less comfortably in its lifespan

made me happy. What more could one ask for? Shortly before the death of Serge

Daney in 1992, between other things, he confided to me his surprise and regret

that I never got the chance to further excel and take on more responsibility at

the heart of this magazine. He had his own thoughts on this issue. I explained

to him the diverse reasons. Without knowing it, several years later, Serge Toubiana

exercised Daney's wish, which was also my own, but sadly arrives negatively,

because Daney didn't see this, which is a regret. The world is sometimes good

to you even though life in general, under certain circumstances, with no

relation to the other things that are going on, can show itself to be cruel.

To the reader of Cahiers, which I was once one, with

fervour and passion, directly, starting in the mid-Seventies, month after

month, and then the catching up as much as I can with all the ancient issues that

were available. So before I even started writing and reading it, in a different

life but with the same sentiment, then joining and participating in its

elaboration, and becoming attentive in a different way to those that read it

and to the remarks of those that write here. To be finally under the obligation

to quit these responsabilities for good does not leave one indifferent, this

goes without saying. But at Cahiers, where one becomes tied to an

intricate bond with others and the network that one creates - with the past,

present and future - never leaves one indifferent. Except when the unsaid makes

on cringe (irritation, a bad conscience) and the explicit also bothers

(unanimity, and the misplaced).

It was my status

of a young subscriber to this magazine that I owed my first visit to the Cahiers offices, which was already at

Boule-Blanche, because I need to ask for why each month I was getting the

magazine so late when it was already on the newsstands. Going through the

office doors has become for me a regular ritual with slight variations

depending on the occasion: bringing in an article, to learn about press

screenings, to take part in a group meeting or to attend an informal discussion

on a film that’s puzzling the magazine, with the desire to discuss or to run

the risk (sometimes) of bothering them, depending on the availability. Before

knowing how it is like from the other side, to live through the transition into

the team, as a paid writer. I don’t need to get into what it’s like to join Cahiers and what that experience was for

me (that’s another affair, another story, which is really complex, and that

I’ve interiorized. I have the feeling of having lived there during those

months, constructing its table of contents and pages).

To be a reader

of Cahiers, that is what I’m

returning to, like before, but also not like before. It will be a new pleasure,

that I haven’t experienced for a while (that of not knowing what will be in the

next issue), which will be richer because of what I’ve experienced at the heart

of the magazine.

It’ll be a new

chapter for me of reading Cahiers,

attentive, exigent and engaged, like always: reading it is a critical activity

in itself, a prolonguement of the gesture that created this magazine,

transmission.

Charles Tesson, December 2003.